The Battle of Quebec - 1759

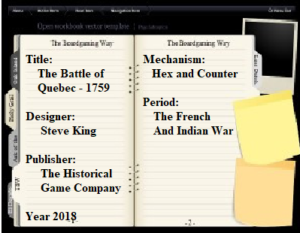

My own introduction to this design came via a video by Gilbert Collins on YouTube. His obvious enthusiasm for this simple, unpretentious design, rather piqued my own curiosity. And then one thing led to another, for not only did I want to hunt down a copy of the game for myself, but I also became interested in the company’s (The Historical Game Company) other published design, Fields of Battle Vol 1 – Battles of The Great Northern War.

My own introduction to this design came via a video by Gilbert Collins on YouTube. His obvious enthusiasm for this simple, unpretentious design, rather piqued my own curiosity. And then one thing led to another, for not only did I want to hunt down a copy of the game for myself, but I also became interested in the company’s (The Historical Game Company) other published design, Fields of Battle Vol 1 – Battles of The Great Northern War.

In a real sense, this article is really a curtain-raiser for my forthcoming look at that work – to be presented on this site in the not too distant future. Fields of Battle Vol 1 is packed full of battles, with each played on its own dedicated map, albeit the units are drawn from a generic pool. Component-wise, the quality is very similar to Hollandspiele – thick counters of the same manufacture, similar presentation of the rules document, small footprint, and a serious emphasis on ease of learning and playability.

But what of Battle of Quebec -1759? This is very much an entry-level game, albeit one with some nice narrative touches, and a definite feel of two contending armies with very different challenges facing them. The game begins as battle is about to be joined – Wolfe has disembarked his modest-sized army from the St Lawrence, climbed to the Plains of Abraham, and is now being confronted by a French army that, potentially, has far greater force it can bring to bear. However, the French have also committed the cardinal military sin of being divided between several different locations. If the British are able to strike quickly and effectively, there is a good chance the forces of Montcalm will be overwhelmed before either the Quebec garrison bestirs itself to do something more than look at the smoke, or some other handy contingent of French troops arrives on the field.

But what of Battle of Quebec -1759? This is very much an entry-level game, albeit one with some nice narrative touches, and a definite feel of two contending armies with very different challenges facing them. The game begins as battle is about to be joined – Wolfe has disembarked his modest-sized army from the St Lawrence, climbed to the Plains of Abraham, and is now being confronted by a French army that, potentially, has far greater force it can bring to bear. However, the French have also committed the cardinal military sin of being divided between several different locations. If the British are able to strike quickly and effectively, there is a good chance the forces of Montcalm will be overwhelmed before either the Quebec garrison bestirs itself to do something more than look at the smoke, or some other handy contingent of French troops arrives on the field.

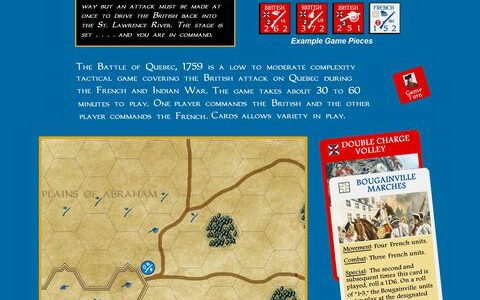

Units come in a number of different types – infantry, artillery, and a very small number of dragoons. However, the finer differences pertain to variations found in the predominant arm – the infantry. Here, the British have the advantage providing they do not end up being overwhelmed by sheer numbers. The British infantry force is either regular troops or elite regulars – such as the regiment of Highlanders and the Royal Americans. By contrast, although the French have a pretty exotic host – rather drawn from the pages of James Fenimore Cooper – a lot of it does not have the durability of the British regulars. Their Coureurs de Bois and Native Americans have lower defence factors than any British units, meaning they are simply easier to damage in most circumstances. Furthermore, beyond the numbers on the units, there are the modifiers contained in the small decks of cards that drive the game – for not only do you and your opponent each draw a card to determine your scope for actions that turn, many cards also add an edge to what combat is then permitted. And overall, the British simply get more positive modifiers, while several of the French cards (and remember, there are only eight each) are all to do with dangling the faint hope of reinforcement before you and then taking it away again.

Units are rated for several things – the main numbers are (L to R) firepower; defence; movement. The small number above the firepower figure is the unit’s range. Units are flipped to show disorder, whereby any affected unit will essentially exist as a sitting target unless/until they are rallied – automatic unless the unit in question is in an enemy Zone of Control. Combat merely consists of rolling a d6, adding the unit’s firepower plus any modifiers, and if the result is at least equal to the target’s defence factor, you start doing damage. Results higher than 1 over the defence factor will eliminate the unit in question, but limited events do allow the occasional unit to return.

Units are rated for several things – the main numbers are (L to R) firepower; defence; movement. The small number above the firepower figure is the unit’s range. Units are flipped to show disorder, whereby any affected unit will essentially exist as a sitting target unless/until they are rallied – automatic unless the unit in question is in an enemy Zone of Control. Combat merely consists of rolling a d6, adding the unit’s firepower plus any modifiers, and if the result is at least equal to the target’s defence factor, you start doing damage. Results higher than 1 over the defence factor will eliminate the unit in question, but limited events do allow the occasional unit to return.

The design notes make no pretentions about the game being anything other than something for casual play and something different for a museum shop. Experienced wargamers might well pick up on the dubious ability of the attacker to get the first shot in – there is no provision for what would normally be termed ‘Defensive Fire’ – but then, it seems pretty clear that the overriding ethos is one of creating a fun and, in broad terms, a valid wargame experience.

And it is important to remember that what is driving a sense of realism in the game is the cards. Both sides have eight each – and in typical card-driven form, those cards each contain an event plus an ability to move and battle with a variable quota of units. The events pertain to incidents from the actual historical battle, as well as expressing the potential of particular unit types. Both unit capacities and events come into play with each card – no choosing one or the other.

The game is played, potentially, over twenty-four turns. As there are eight cards in a full player hand, and as the prospect of French reinforcements (apart from the Quebec garrison) only begins to take shape after the first reshuffle, the game’s progression can be divided into three groups of eight turns each.

If the British get to do some serious damage in the first eight-turn period, and that without taking too much hurt in return, the French player will be chasing the game and will be even more desperate for his reinforcements to arrive while there is still some army for them to augment. The Quebec garrison can appear in the first period, but it is likely that the period will be well advanced before the French player draws the relevant card, and then he/she has got to roll a 1 on the d6. In other words, best not to hold your breath on that one. It must also be pointed out that the garrison is not the last word in military potency – a fair amount of it is artillery or lower grade troops, neither of which is best suited to the situation they are likely to find themselves in. Artillery is more of a nuisance weapon in the game that will rarely be used in abundance owing its restricted effect (no creating eliminations when firing at longer range) as well as card limitations on how much of anything can be active at one time -most of the time you will spend what you have driving your infantry on. As for the militia types, their greater vulnerability can lead to them sitting lost in the eliminated box unless a few propitious die rolls can be mustered.

If the British get to do some serious damage in the first eight-turn period, and that without taking too much hurt in return, the French player will be chasing the game and will be even more desperate for his reinforcements to arrive while there is still some army for them to augment. The Quebec garrison can appear in the first period, but it is likely that the period will be well advanced before the French player draws the relevant card, and then he/she has got to roll a 1 on the d6. In other words, best not to hold your breath on that one. It must also be pointed out that the garrison is not the last word in military potency – a fair amount of it is artillery or lower grade troops, neither of which is best suited to the situation they are likely to find themselves in. Artillery is more of a nuisance weapon in the game that will rarely be used in abundance owing its restricted effect (no creating eliminations when firing at longer range) as well as card limitations on how much of anything can be active at one time -most of the time you will spend what you have driving your infantry on. As for the militia types, their greater vulnerability can lead to them sitting lost in the eliminated box unless a few propitious die rolls can be mustered.

There are better prospects, albeit later on, of getting one or other of the two marching French columns onto the field – each has a 50-50 chance of appearing when their trigger cards are drawn. But frankly, unless something utterly untoward happens on the map, if they do not appear, or players shun the option to bring them on anyway (a play balance game variant), the French player will be rather up against it.

The game is won by unit elimination – a bit too much elimination if I am honest. Yes, this is meant to be a fun, introductory sort of game, but the conditions do lack a bit of subtlety as both sides seek to kill near everything in an opposing colour. There are obvious problems with this, and I do feel it detracts, just a little, from the nice bits of shading at work via the card events and unit capacities. There are several ways of presenting this, but I will settle for the one that occurred in my main trial game The original French field army was all but annihilated by the time one of the French reinforcing columns came into view, and in the real world, that column would simply have turned around or sought to get into the shelter of the city – not go plunging into a last-gasp exercise in total futility.

Then again, this is meant to be an entry-level design and it does model a battle that was verging, historically, on being next to no battle at all. The French advanced, offered two indifferent volleys, and then got blasted away by the British return fire. And that, apart from a hasty pursuit, was just about it.

Something I must stress is that playing the game was very enjoyable – noting areas, where things can be questioned, is a natural part of analysis, but that is quite different from issues of whether I had a good time with the game…which I did. This last photo should make it clear that the design looks very well, and in addition to that, it plays in a snappy and engaging way. I did feel there were one or two areas where a bit more exposition in the rules would have helped – such as what the Quebec garrison does if it is released but its exit hexes from the city are blocked by the British, and how exactly the French off-map reinforcements file onto the map and again, how is that changed if the British are right on top of them?

Something I must stress is that playing the game was very enjoyable – noting areas, where things can be questioned, is a natural part of analysis, but that is quite different from issues of whether I had a good time with the game…which I did. This last photo should make it clear that the design looks very well, and in addition to that, it plays in a snappy and engaging way. I did feel there were one or two areas where a bit more exposition in the rules would have helped – such as what the Quebec garrison does if it is released but its exit hexes from the city are blocked by the British, and how exactly the French off-map reinforcements file onto the map and again, how is that changed if the British are right on top of them?

Finally, the design does have the merit of being one of the very few games to feature a battle fought on Canadian soil. These are as rare as hen’s teeth, and thus it is only right to commend anyone who points their design attention that way. If you accept it for what it is, which is what it was always meant to be, you will get some fun out of it.

Paul Comben

Battle of Quebec – 1759 BGG page

Battle of Quebec – 1759 BGG page