By Mitch Freedman

Antietam – Burnished Rows of Steel – A Boardgaming Way Review

As a battle, Antietam was a mess. It was a glorious mess, bravely and badly fought, and as the sun set it marked the end of Robert E. Lee’s invasion of Maryland and cast a long, long shadow that reached all the way to the end of the Civil War.

It’s hard to know, even today, just how much weight to give to the battle of Antietam in the long chain of events which led to the end of the Civil War. It was a turning point – a big one – but great results can have many causes and what seems significant or inevitable now was not quite as certain or obvious right after the battle.

Certainly, supporters of the Union claimed a great victory on September 18, 1862. The day after the battle, things looked very good for the North. After defeat after defeat, the federal Army of the Potomac had finally stood up to Robert E. Lee, even though it was in no shape to chase him back through Virginia. And Maryland, always a threat to leave the Union, remained as fragile and loyal as ever.

In the Confederacy, people saw their brave, outnumbered army hold off powerful foes and hold the field, at least on the day after the battle. And, a moral victory in the north was no small thing for the Army of Northern Virginia. Once the truth was spun, a great victory could eventually be declared by politicians and newspaper editorials in both the North and South. Until the casualties became widely known.

Certainly Sept. 17, 1862, was the bloodiest single day of combat ever seen by Americans — 22,717 dead, wounded and missing on both sides — and it is widely credited that Antietam gave President Lincoln the political cover he was looking for before issuing the Emancipation Proclamation. That put the Civil War in a new light, and kept Britain and France from aiding the South by recognizing the Confederacy.

But, as an educated guess, Lincoln probably could have found another reason to issue the Emancipation Proclamation if there was a different battle somewhere else that seemed to end well for the Union.

And all of that makes this battle special.

A lot of board games have been written based on the Antietam — there’s even a top 10 list of them, a rare honor for a single day’s event in any war — and Antietam: Burnished Rows of Steel does a good job of highlighting many of the special factors in the battle. And, it also does a good job of showing that things aren’t always what they seem at first glance.

The Big Picture, the Little Picture

This is one of those games where a lot of little things add up quickly to big ones, almost before you really notice them. It’s really important, for example, to take a good long look at the victory conditions before you play. That seems obvious, but any Union general who forgets to keep them in mind and just concentrates on beating the enemy is almost sure to lose.

The Antietam – Burnished Rows of Steel map.

The Confederate doesn’t really have a chance to determine the flow of the battle. They really are much too busy reacting to overwhelming Union force, floating away like a butterfly and sometimes stinging like a bee.

From casualty charts which make artillery less effective against small units to rigid non-cooperation rules that block a broad coordinated Union attack, the game creates special problems and gives special opportunities to both sides. And, there is an elegant simplicity in the small rule that no Confederate unit can come within two hexes of the Middle Bridge, eliminating the need for special Union cavalry rules to cover units assigned to the single task of blocking any enemy advance.

Problems and Opportunities

Players also have a price to pay for a game system that shows unit attrition and how it rapidly changes the odds in any battle.

This game has lots of counters. Lots and lots of counters.

“Antietam – Burnished Row of Steel” contains a little less than two sheets of counters.

Individual infantry units on the Union side have three separate counters, printed on both sides. As units get weaker, they are flipped over, then replaced, and flipped again. And, no unit ever recovers its full combat strength once it suffers a combat loss.

It’s important because combat results get better if you attack with even one strength point more than your enemy. And, since artillery fires before infantry, you may be able to soften up a target before the attack to change the odds.

On the other hand, shot-up units can get back most of their strength if they simply move out of range and rest for a turn or two. Think stragglers coming back, and some of the wounded returning to the lines.

Then there are the fragile units which don’t have the strength to keep turning over. One or two attacks and they die.

A portion of the Combat Results Table for “Antietam – Burnished Rows of Steel.”

Many games resolve battles using a strength ratio, the attacker has a 3-1 or 4-1 strength compared to the defender. Antietam is a little different.

* The odds table, which has many die roll modifiers, allows no attack where the attacker is more than one point weaker than the defender, and goes up through 0, +1 and +2. The highest attack allowed is a 2:1 strength ratio.

Most attacks involve step losses to both the attacker and defender. At -1, there is a chance of the attacker losing more than the defender, while at 2-1 odds the defender usually loses two steps and can suffer a mandatory retreat (or lose another step if they can’t) .

It’s more important than it might seem at first. If a unit attacks, each unit it touches must be attacked. That means splitting your attack strength or having another unit attack as well. This can lead to a whole line of units firing, and one of those attacks is likely to be at low odds.

* A D-6 is rolled to resolve all attacks, but there are bonuses for surrounding an enemy, a modifier for relative morale of units (which drops as they get shot up) and a defensive bonus for terrain. The modified rolls can go from -1 to 11.

* Artillery fires independently, and cannot move and fire in the same turn. The artillery fire comes before infantry attacks, which can change the odds for friendly troops. A cannon moved in one turn can fire on an attacker in self-defense in the next turn.

* Artillery results are determined by the strength of the gun, the distance to the target, and cumulative effects of terrain. More than half of the potential attack results will only harm another artillery piece or an infantry unit with more than three remaining steps.

There are also die roll modifiers that give better results at close range, and poorer results at long range.

Hint, Hint

It is really important for the outnumbered Confederates to use a strategic withdrawal and rebuild their bigger units after a heavy loss. And, they also have to dig in and slow the Union advance, even if it means the loss of the entire unit. Tough choice and one that can be dictated by the enemy attack – never a good way to fight a battle.

It is really important for the outnumbered Confederates to use a strategic withdrawal and rebuild their bigger units after a heavy loss. And, they also have to dig in and slow the Union advance, even if it means the loss of the entire unit. Tough choice and one that can be dictated by the enemy attack – never a good way to fight a battle.

But the Union is the player who must go on the offensive. And as you play, the Union general will find that success on just one part of the field won’t guarantee a victory.

It’s a little upsetting, around mid-game, to see all those Union Corps which have never gotten into the battle, and to watch the game turn marker work its way down to the end.

Attack and attack again, by all means. But if the Confederates can dance away, and perhaps come back and claim a critical victory hex, your attacking is not winning.

When I fight with Roman legions or massed Austrian infantry, I usually just send waves of troops out across the board while looking down with a perfect bird’s eye view. Antietam reminds me that those generals didn’t have radios or field telephones, and that even the observers in hot air balloons couldn’t provide a full picture of the battlefield, let alone help commanders on the ground see the big picture.

The final Union assault on “Burnside’s bridge”, the linchpin of the Confederate right flank position.

Score one for the Rebels. While the Union side generally drives the attack, the Confederates drive the all-important retreats and regroups. Robert E. Lee and his commanders have to decide just how far to pull back, and just how long to stay back before re-engaging, and when the Union attacker becomes over-extended and is a ripe target for a counter-attack.

Of course, just where the Confederates choose to withdraw depends on which Corps the Union activates for its attacks. Just two Union corps are allowed to attack at any time. And, when one corps pulls out to regroup, it might not get activated again.

Again, the rules seem to make the choice simple. The Union’s I Corps (Hooker) is automatically activated on Turn One, and the Union player gets to pick just one other Corps – XII (Mansfield) or IX Corps (Burnside) – to start the game. VI Corps (Franklin) is available, but cannot be committed until turn 7.

In a way, that’s the mirror image of the Confederate’s problem. Lee’s troops may not know where to retreat to build up their strength, but the Union player has just as big a problem with committing his troops and then pulling out of the battle. When individual units are shot up, they can retreat — at least five hexes from the nearest enemy — and start to recover. But when a Corps is pulled back, it then becomes unavailable, at least until the general rolls a 6 on a D-6 die.

So, the Union army could end up retreating out of the very hexes it needs to meet its victory conditions. And, the Confederates can advance back into those victory hexes, but could face being cut off and attacked by another Union Corps activation.

Try it once or twice, and you see it’s not an easy task at all. But, whoever said being a general was easy?

The Game Beyond the Board

The Antietam campaign – September 3rd through September 15th, 1862. The battle of Antietam is also known as the battle of Sharpsburg.

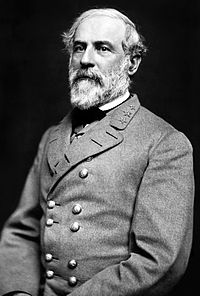

Some myths and legends arose from the bloody fields of Antietam — we can call it Sharpsburg from the Confederate perspective — and one myth died. That was the aura of invincibility of Robert E. Lee and his Army, a myth that proved to be worth many brigades over the years in a war where morale often decided the outcome of a battle.

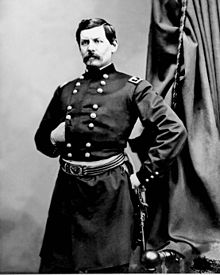

1861 Matthew Brady portrait of Union commander George B. McClellan.

No one can know what went through the minds of the commanders in the fields or of the troops who fought bravely on both sides. But, everyone today – at least in the boardgaming world — “knows” that the Union attacks were generally incompetent, badly coordinated, and that Union Major General George B. McClellan was, as usual, nearly paralyzed with fear. We know that McClellan believed he was badly outnumbered, and could have ended the Civil War two years earlier had he just fought with even modest competence.

On the other side, a lot of people will say that Robert E. Lee fought with almost inspired brilliance, coolly and competently shifting his troops from one part of the battlefield to the other, avoiding near-certain defeat and managing to hang on until — at the very last minute of the very last hour — A.P. Hill’s division arrived from Harper’s Ferry and launched a surprise counterattack in just the right place, driving back Major General Ambrose Burnside’s Corps and giving Lee the chance to withdraw his battered army to fight another day.

This game gives the Union player more than enough Union troops to win the game. Just put them in the historic Corps areas – the Confederate placement is mostly-historic as well – and begins the battle. The Union player will quickly begin to share McClellan’s frustration, while the Confederate general will feel the pressure faced by Lee, realizing that all they can do is counter-punch when the opportunity presents itself. And, that it’s the best way to win.

Unit Placement – The good news

While the combat units on both sides are generally placed where they actually started, both sides have enough flexibility to get into trouble.

The greatly outnumbered Confederates place their troops first. Their only major initial decision is which infantry units will get artillery support, and where a pitifully small reserve will be set up. Looked at the right way, it looks almost as if the key to the entire battle is just where in the Sunken Road D.H. Hill’s units dig in.

The Union player gets large Corps areas in which to distribute his troops, and only a few of them will be in the front lines.

The Confederates have interior lines, and the ability to move faster than the lumbering Union troops.

Hooker and Mansfield, Porter and Burnside, Summer and Franklin have huge footprints on the battle map. They don’t exactly surround the Confederates, but with the Potomac River cutting off escape, they are in a perfect position to attack on a broad front and rout their foes. But the rules won’t allow it.

And artillery, even from inactive units, can fire at the enemy, providing they have the range and a clear line of sight. The Union troops seem to have all the big guns anyone could want, especially long-range Parrot guns, which can take out enemy troops from half way across the board.

If only the trees and hills and other terrain were not in the way.

The unit markers have different colors to make it easy to see which division goes where, and since it is illegal to combine units from different Union corps in a single attack, it’s a handy thing to have.

Unit Placement – The bad news

All those Union troops eventually find themselves having to use roads or go through a woods area – movement problems which hamper any chance of attacking in that broad front that looks so appealing for a first-time gamer. And, no matter how units are placed, some of them will be blocking roads, or unable to fire because woods or hills are between them and the enemy.

And, trying to mesh attacks between just two of the available Corps is a lot harder than it might seem. The game replicates the mind-set of generals who did not trust each other, who wanted more glory for themselves than their rivals, and who were hampered by lack of fast and accurate battlefield information.

In truth, it would be hard to coordinate a massive attack on this battlefield even if it was flat and clear and every general had the movement plans of everyone else on their side.

Anyone who has ever marched, even in a squad formation, knows it’s harder for eight or ten men to move in a straight line than it is for one person to walk down a street.

Put a few squads together – say one platoon with a headquarters and three rifle squads – and just getting them from one corner of a parade ground to the other takes a lot of practice.

Now, take 20 or 30 counters for one Union Corps area, throw in some woods and a road, and add some blocking terrain – woods or hills – and make it so the quickest way to attack an enemy is a crooked line, and you see the challenge of simply setting up.

The Union player gets to do it for every corps, and those wonderful Parrot guns have to have a line of sight before they can hit an enemy, which is hard to do given their initial Corps set-up area.

So, all the Union player has to do to win is get fresh troops to the front, get artillery just where it’s needed, and try to keep all those shot-up troops out of the way. If only he could.

And, all the Confederate player has to do is respond to Union moves with lightning-swift counter-attacks with his few powerful units while protecting them from withering artillery fire, and pull them back to regroup after they become too weak to counter-attack after the first two or three rounds of battle. Unless they are really needed.

It leads to a long, bloody and frustrating battle for both sides, with flashes of hope and danger, and the winner needs to be lucky and good.

In short, it creates what must have happened at the Battle of Antietam.

Resources: