by Paul Comben

An analysis of the British Battle Cruisers at Jutland

It is common for historians seeking to explain the failures and frustrations surrounding the conduct of the British fleet at Jutland to point a finger at that long period of unchallenged naval supremacy which followed the battle of Trafalgar. The argument is well known: the Royal Navy became too enamoured of tradition, appearance, and protocol during those long years of relative idleness, and thus lost the edge of verve and application which had been so much of the reason why the navy had triumphed in the first place. The senior service might toast the memory of Nelson; but the evocation of ghosts and past victories was a poor substitute for firing guns instead of incessantly polishing them.

It is a solid argument, but it is not the whole argument; for beyond the legacy of Trafalgar there was another British victory in the selfsame war, which, in its own way, tells its own story as to why three battle cruisers were torn to pieces at Jutland, and why the battle ended with the Grand Fleet staring at empty sea rather than the blazing remnant of the Kaiser’s navy.

So I will dispense with Trafalgar, and begin instead with Waterloo. According to one of the Duke of Wellington’s most famous quotes, it was all won “on the playing fields of Eton.” But that hardly squares with his other famous quote, that it might not have been done “if I were not there.” It can rightly be considered a shame that the Duke’s fundamental decency was often overlain by the aloof traits of his social background; but the simple reality of his management of the armies he commanded with such a high degree of personal supervision reveals just how little faith he had in the Blackadder princes who populated the commissioned ranks of his forces. Among the many events of that battle on June 18th 1815, one that speaks volumes as to the nature of the well-to-do men in the red coats occurred, as at least one historian has cited, when an aide from Earl of Uxbridge conveyed an attack order to a regiment of British cavalry, and was cordially invited by the unit’s commander to “join in” the charge – an invitation Uxbridge’s fellow was delighted to accept. Not once did it occur to the enthusiastic dolt that he might be needed by Uxbridge for pressing duties elsewhere; no, he was off after the French fox and the wild mad dash to the best kind of sport.

And so, whilst elsewhere on the field, Congreave’s rockets were shooting off here, there and everywhere, and Thomas Picton was dying an eccentric hero’s death when a ball smashed into the top hat he was wearing (he had worn a nightcap during one Peninsular battle), and while officers out of Eton showed the form and fell with a nonchalant air, the cavalry charged on their magnificent horses, routed the French infantry of D’Erlon’s corps, and then, with all the happy abandon of fellows putting up some scurrying beast across the fields of Hampshire, ignored the recall, pointed themselves more or less in the direction of Paris, and were swiftly decimated by the Guard light cavalry and the lancers of Jacquinot’s division.

How does this link to Jutland? Follow the progression: much the same sort of army (and navy) went to the Crimea close to forty years later – but there was no Wellington to watch out for error. The ensuing campaign was miserably conducted by plummy chaps with plum stones for brains, and the British soldier was culpably starved and materially denuded. A flavour of this can be readily gleaned in the 1968 Tony Richardson film, Charge of the Light Brigade. Had Wellington been there, despite being described (unfairly, in my opinion) in Esposito and Elting’s Atlas of the Napoleonic Wars as “Ungrateful, vindictive, something of a toady and more of a snob,” let there be no doubt that those responsible for the entire incompetent catastrophe would have been peremptorily strung up and then thrown lifeless and shamed into waters off Balaclava.

Of course, the most famous event of that war was the charge immortalised by Tennyson – once again British troopers went thundering towards catastrophe, sent hurtling off by the muddle found in a specious order, and led by a womanising old goat by name of Lord Cardigan. Does this link to Jutland and those battle cruisers? Well, we are getting there. Early in the Great War, near an entire British naval squadron was destroyed off the Chilean coast at Coronel. It was destroyed because the First Sea Lord, Winston Churchill, could muddle an order with the best of them, and not for the first time, was more concerned with how things sounded than with the practicalities of what needed to be done. And to cap it all, the admiral on the spot, Christopher (Kit) Craddock, felt honour bound by the obligation of British naval history to go after a superior German force because, well, it was there. And then we are back with the foxes again, with the naval equivalent of the equine dash of the Union and Household brigades at Waterloo, or Cardigan’s flogged troopers at Balaclava, readily equated with the charge of the Good Hope and Monmouth towards the fire directed at them by the German ships. In the aftermath of the defeat, Admiral Arbuthnot, whose bully-boy demeanour and crass idiocy would wreck his own squadron at Jutland, lamented the loss of Craddock, but consoled himself that his friend had always hoped to die either in battle or in the course of a hunt.

What this is all leading to is that the hundred years or so which separate Waterloo from Jutland were, in Britain, filled with the recurring themes of eccentricity, social division, the manifest complacencies of the old aristocracy as well as the industrial and commercial nouveau riche; of bright ideas being hatched in garden sheds and ramshackle huts, with a queen who spent a large amount of her reign feeling sorry for herself, an education system which taught dead languages to the moneyed and inbred, and a general feeling that everything supposedly of worth and purpose in life was only to be properly understood and expressed by finding the right sporting metaphor to use about it. Such a society could, and did, despite of everything, produce its great talents, but it was never going to face up properly to the challenge of an increasingly scientific and industrial world. Perhaps only an Englishman could have brought what amounted to fireworks to Waterloo, but that sort of world, expounding casual ascents of the Matterhorn in one’s carpet slippers, had come close to running its course.

And then, as we enter the last century, another clever eccentric appeared out of the haphazard workings of British life, and this was that hectic power at the Admiralty, Jacky Fisher. In the words of one of his present-day relatives, the entire Fisher family were rather on the mad side. Among his contemporary family was the first wife of the English composer Ralph Vaughan Williams – she, Adeline Fisher, only seemed to come alive when there was someone ill to look after; and then, having lost a brother at Jutland, she wore black for the rest of her life. Fisher himself was a seething mass of conspiratorial tendencies, but, when on form, he was capable of producing flashes of real brilliance. It was thanks to Fisher that Britain astounded the world with the battleship HMS Dreadnought in 1906 – faster, better armoured, and above all else, far more powerfully armed than anything that had gone before. It was a ship for the nation to be proud of, and Fisher made certain there would be plenty more of that kind to be proud of before the government really caught fright at the size of the bill. This he did by having readied the yards for the building of several more Dreadnoughts, and ensuring that political friends as well as the broader public were caught up in the enthusiasm for the new ships. The government was thus presented with what amounted to a fait accompli, whilst the music halls resounded to the words first voiced by a Unionist MP: “We want eight and we won’t wait!”

But what Fisher really wanted was fast ships – very, very fast ships; ships that would combine the hitting power of the new battleships with the speed of cruisers. These ships could get after commerce raiders, aggressively scout for the main body of the fleet, and do so possessing the power to deal with any mischief along the way, whilst having the speed to get out of the way if anything too big and formidable came along. This was a role he had first envisaged for the armoured cruiser; but now these were yesterday’s technology, and the new breed, the battle cruisers, were due to come into their own.

“Speed is armour” was the essence of Fisher’s doctrine – and up to a point, it made perfect sense. Think of the Red Baron in his Dr1 and a competent pilot in a Spitfire – it is not difficult to work out who is going to get shot down and who is going to land safely with not so much as a bullet hole anywhere. On the other hand, if the gun sight in the Spitfire was a bit iffy, or the Spitfire pilot wanted to give the Baron a “sporting chance,” or there is some fatal frailty about the Spitfire somewhere, it might be a different story. In actual war situations involving aircraft, the Japanese Zero embodied the “speed is armour” concept, which worked out pretty well to begin with – until the thoroughly unprotected Zero was put up against US planes that could catch it and blast away at it.

In truth, whilst there were several things right with Fisher’s battle cruiser concept, there was rather a lot that was seriously wrong. On the plus side, the British ships of the evolving BC classes, the Invincibles, Indefatigables and Lions, were fast, better armed than the German ships built in response, and there were of course, more of them than the Germans could build for their own fleet. But the negatives were serious, though in some cases somewhat subtle and difficult to identify at the first.

In total, the issues with the battle cruisers were a combination of questionable ideas of conduct and doctrine, combined with those flaws which British attitudes over the years since Trafalgar and Waterloo had defined as the nation’s ability to compete, or not compete, in the modern world. The most obvious flaw with the battle cruisers was the lack of armour – they had armour, but not as much as the German battle cruisers, and in the equation which was meant to balance speed against hitting power and the ships’ ability to withstand punishment, Fisher’s preference for speed and more speed meant that something had to give, and that was the armour.

This still might not have been such a death sentence as it proved to be, had the British used the battle cruisers solely for the roles first envisaged – scouting for the fleet and pursuing raiders. The role of chasing raiders worked pretty well at the Falklands in late 1914; but these British ships were big, were flashy, (Beatty called the later classes his “Big Cats”), had large calibre guns, and perhaps inevitably they drifted more and more into the operations of the main body of the fleet, and were counted more as fast battleships than as something truly apart and different. Expecting them to fight ships that were close to a match for them was asking for trouble, and that trouble was exacerbated by poor tactical decisions and flaws with key parts of British technology.

In short, all of Fisher’s ideas, the good ones and the plain awful ones, were all coloured by the problems with what we can call British science and British industrial application. The British could build a lot of ships, but these were all restricted by the old yards they were built in. Nothing new had been built to put something new in, which, amongst other things, restricted the beam of the new classes, and made them less stable gunnery platforms. And then there would be the issues with the quality of British armour piercing shells, and most of all, with the system by which they were pointed the way of the enemy. Placed on the desks of the admiralty in the years leading up to the Great War was the director system created by one Arthur Pollen. Contrary to what one might naturally expect, Pollen was neither a major boffin at a major university (besides, Britain did not have many universities, and those there were, were of the kind you could get into with three Fs – Father, Finance and a Fine Old Public School); nor was Pollen beavering away at a hush-hush government department. In the words of eminent naval historian Norman Friedman, “He was that typical British creature, a brilliant and very persistent amateur.” Pollen may not have been putting his incredibly complex mechanisms together down at the end of the garden, but the essential ethos was there. A system which would help give the massive guns of the Royal Navy their best chance of hitting, and keep hitting, the power of the enemy at range, was being put together without a penny from the state, and with neither the navy itself nor any department of government taking an early and active part in promoting and honing the design.

The navy did not hear of Pollen’s system till it arrived, and then the truth was that they neither wanted to pay for it, nor, in all likelihood, really understood and appreciated it. It probably did not help that it was not a navy man putting the design forward, and what with the cost, the intricacy, the folly of doubt (madness, given the reach of the guns) over whether such a long range system was really necessary, and the general drag weight of bureaucracy, the Pollen system was left largely in a state of limbo. Instead, naval attention eventually turned to a navy officer’s submission – the Dreyer table. Dreyer’s design could do the same sort of job as the Pollen device, but it was, overall, not as precise and refined, and its performance fell away at the higher rates. Nevertheless, the essence of the two systems was that once you had the right range to target, and all the other correct elements had been fed in, a British ship so equipped could better hold its target lock whilst either friend or foe engaged in more drastic manoeuvres. Again, fed by lingering scepticism and dislike of spending the money, director systems did not exactly pop up on British battleships and battle cruisers with any real haste, but by Jutland nearly all the British capital ships had a Dreyer table as part of a complete director system, and a handful actually had the full Pollen system (the BC Queen Mary was the most notable ship with the full works, and perhaps it is no surprise she was one of the best gunnery ships in the fleet – for the brief time she was around).

So far so (reasonably) good, but it all got spoilt by the inferiority of the British rangefinders. The stark contradiction in having guns that could fire to over 20,000 yards and rangefinders that became inaccurate once past 15,000 yards or so was not something the navy did anything positive about. “Speed is armour” was all very good if you had the full works and the tactical savvy to outrange your enemy and pepper him with accurate fire; but partly through the aggressive predilections of David Beatty and mainly through the inferior lenses and overall design of the Barr and Stroud rangefinders, at Jutland the British battle cruisers got far closer to the Germans than they should have needed to – and paid the price.

It was really at the Falklands in December 1914 that the first warning signs appeared with regard to the battle cruisers’ use and abilities. Two of them, Invincible and Inflexible, had been sent south to destroy Von Spee’s bothersome East Asia Squadron, led by the battle-hardened armoured cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. The interception of these ships worked well enough, despite the two British BCs being caught in Stanley harbour as the Germans appeared; but holding off at range and comfortably ruining the German ships without fear of reply was utterly negated by the awful shooting of the British ships at longer range – something not helped in any degree by the vast amounts of thick black smoke produced by the two BCs as they moved at speed. Furthermore, as was seen after the fight, the armour on these ships was not up to preventing the penetration of German 8.2 inch ammunition at moderate ranges – and the German battle cruisers mounted 11 inch and 12 inch guns.

Bad gunnery was repeated at Dogger Bank in January 1915. Tiger, the newest battle cruiser, hit absolutely nothing except the sea, and Fisher, incandescent, had her gunnery officer sacked. It was painfully obvious that more attention needed to be paid to accurate gunnery instead of polished and glinting guns, but rather than do that, the British BC squadrons opted for a different solution. What this idiotic “fix” consisted of was firing a vast amount of shells at the enemy in the hope that sheer weight of fire would cause some hits sometimes. Of course, firing rapidly meant that you risked expending all your ammunition with the battle still ranging, and such a rate of fire also relied on feeding the guns faster than normal procedures would allow. So, not only were the BCs seriously overstocked with shell and cordite to prevent them running out, they were also to see crews cutting corners all over the place to keep a ready supply of ammunition to the turrets.

For a long time after Jutland, the catastrophic loss of three battle cruisers was assigned purely and simply to thin armour failing to stop German shells plunging right through to the magazines. We now know, however, through archaeological dives to the wrecks, that the actual explanation is far more complex. In all likelihood, German shells ignited cordite charges stacked up, protective sleeves already off, in the approaches to the turrets. The cordite should never have been there, shifted through passages completely outside of the designated handling areas; but nevertheless, there it was. Recent dives have revealed charges left lurking in suspicious places around the shattered hulks of these vessels, evidence that these ships’ officers and crews had in no small way contributed to their own deaths by being so reckless with a mass of explosives.

Cavalier attitudes prevail throughout this entire story, whether it is the lack of application to shooting straight, or David Beatty’s failure to give his key subordinates a proper inkling of what he was trying to do. Beatty may have looked the part with his cap perched at such a jaunty, devil may care, angle, but throughout Jutland he persisted in making questionable decisions; and this in addition to not having made any appropriate contingency plans for things which could have been sorted long before a shot was fired– more of that anon. It does, however, speak volumes as to the nature of the man that he spent the greater part of the battle up on the utterly exposed compass platform of the flagship HMS Lion. He certainly would have had a good view of just about everything save the shell splinter that could have killed him at any moment. Lion did have an armoured conning tower, but he was not going down there, dear me no, not on your Nelly.

Jutland’s dress rehearsal was Dogger Bank, which was a much smaller battle but one with striking similarities to the main event a year and more later. The Admiralty’s Room 40 intercepted the German command for the Scouting Group to sortie, the British, in superior numbers intercepted, and the Germans ran for it. Two things then occurred which had implications for events at Jutland: the German BC Seydlitz was nearly destroyed by a magazine explosion as fire moved from a turret hit to the handling chambers. The German ship survived, just, and in the aftermath, the Germans added more doors to the passage between the turrets and handling chambers of their ships. The British did no such thing, having not had the experience at that stage to learn from. What they should have learnt from, however, was the failure of the commands and signalling among the BC squadrons present at the Dogger Bank battle. With his flagship suffering a loss of power as its dynamos failed, Beatty attempted a signal to send the bulk of his forces after the still fleeing Germans, whilst his slowest functioning BC, Indomitable, finished off the stricken German armoured cruiser, Blucher.

However, flying flags like it was regatta time off the Isle of Wight did not work as desired – the signal was misinterpreted and the whole force went after the Blucher. Why commonsense did not kick in is anyone’s guess, but such a frustrating experience should have filled Beatty with a desire to get things right next time and sort out some basic fleet orders – only it did not.

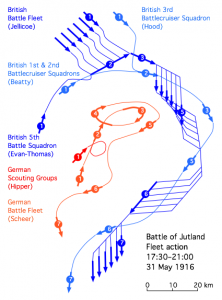

By the time of Jutland, Beatty had secured the services of the 5th Battle Squadron and its superb Queen Elizabeth class battleships. In return, he gave the 3rd BC Squadron to the Grand Fleet’s main body – the squadron consisting of the battle cruisers of the original class: Invincible, Inflexible and Indomitable. Beatty had a good deal here, as the Queen Elizabeths were fast, powerful in the extreme, good gunnery ships, and able to withstand a lot of damage. But Beatty and Evan Thomas, the 5th Squadron’s commander, never sorted out how their respective forces were meant to operate together; and in the wake of Dogger Bank, above all else that meant the simple measure of Beatty saying to his subordinate: “If I do ABC and you cannot see a signal, I want you to conform by doing XYZ.”

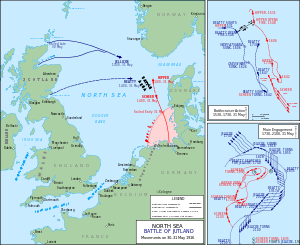

What Evan Thomas actually did in the opening stages of Jutland was not much of anything. Beatty was following reports from his cruiser screen that the German battle cruisers were in sight, and whilst he went tearing after them, because Evan Thomas had not heard or seen anything other than the six battle cruisers changing course, he did not follow from his station, which was already rather adrift of where he really needed to be. Eventually, however, with the two squadrons of battle cruisers moving even further away and clearly picking up speed, the 5th Battle Squadron’s commander thought better of pointing in the wrong direction, and worked up speed to catch up. Nevertheless, these four ships were entirely missing from the opening stages of the battle, which meant that the overwhelming numbers and firepower which should have been brought to bear on the German force was late coming together – and by the time it did, two battle cruisers, Indefatigable and Queen Mary, had already been destroyed.

Beatty probably thought a 6:5 margin was reasonable at battle’s start, but further failure in honing the two BC squadrons’ efficiency put paid to that notion. Again, signalling failed and any pre-arrangement of tactics was not in evidence. Instead of Beatty’s two leading ships concentrating on the German flagship, and then the rest firing by target sequence, some British fire wastefully doubled-up on German ships, leaving others untouched.

British fire was bad – and was not helped by the rangefinders being at even more of a loss when attempting to produce precise readings against leaden skies. The first major casualty suffered by the British that day was the battle cruiser Indefatigable. Near the rear of the British line, she was repeatedly hit and may have already been sinking by the stern when, a little after 4pm, she blew up after several further hits. The much larger Queen Mary, the one ship that had been hitting the Germans repeatedly, suffered a massive explosion about twenty minutes later; and when Princess Royal momentarily became shrouded in smoke and was reported by another member of the contingent on the compass platform of Lion as having gone the same way, Beatty famously turned to Lion’s captain, Chatfield, and said: “There’s something wrong with our bloody ships today.”

Indeed there was something wrong – or rather, some things wrong: ammunition overstocked and all over the place; rangefinders that did not match the reach of the guns; rangefinders that were so off Beatty was 4,000 or so yards inside the range of his biggest guns before he opened fire; the public school dash to the “sport”, bringing the range down at one point to a ridiculous 11,000 yards; want of method; want of forethought; unreliable shells; the “Big Cats” that were really “Eggshells Armed with Hammers”; failing industry conniving in the production of unnecessarily vulnerable ships; eccentric ideas obscuring sound concepts….and so it goes on.  The last act of the tragedy for the “Bloody Ships” was played out in the early evening of May 31st 1916. Admiral Hood, with the 3rd BC Squadron, spotted the battered German battle cruisers appearing out of the mists at a range of only 7,000 yards. The opening shots from the British ships struck home, and Hood called out to his gunnery officers: “Your firing is very good; every shot is counting.” A few moments later, Invincible was hit; the exposed cordite went into a slow burn, building up until there was a massive explosion. The ship broke in two, and in the relatively shallow waters of that part of the North Sea, both halves came to rest on the bottom, with the bow and the stern extremities pointing up out of the waters. As with the other lost battle cruisers, the loss of crew was close to 100 percent. Hood himself was the most senior British casualty of the battle, and in his memory, it was soon decided that the new battle cruiser just under construction in Glasgow, big and British, flawed and beautiful, would be named after him.

The last act of the tragedy for the “Bloody Ships” was played out in the early evening of May 31st 1916. Admiral Hood, with the 3rd BC Squadron, spotted the battered German battle cruisers appearing out of the mists at a range of only 7,000 yards. The opening shots from the British ships struck home, and Hood called out to his gunnery officers: “Your firing is very good; every shot is counting.” A few moments later, Invincible was hit; the exposed cordite went into a slow burn, building up until there was a massive explosion. The ship broke in two, and in the relatively shallow waters of that part of the North Sea, both halves came to rest on the bottom, with the bow and the stern extremities pointing up out of the waters. As with the other lost battle cruisers, the loss of crew was close to 100 percent. Hood himself was the most senior British casualty of the battle, and in his memory, it was soon decided that the new battle cruiser just under construction in Glasgow, big and British, flawed and beautiful, would be named after him.

Paul Comben