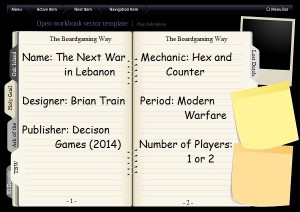

Review by Mitch Freedman

A friend of mine, who knows my interest in the Middle East conflicts and my joy in playing “what if” games (we play a Very British Civil War a lot) recently gave me a copy of Next War in Lebanon.

A friend of mine, who knows my interest in the Middle East conflicts and my joy in playing “what if” games (we play a Very British Civil War a lot) recently gave me a copy of Next War in Lebanon.

I opened it, glanced at the counters and the map, read the rules twice and thought – gee, this looks interesting.

Little did I realize the adventure that little gift would take me on.

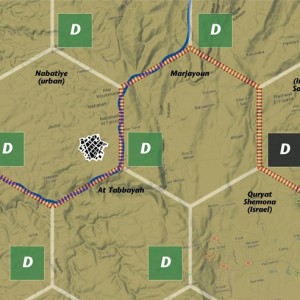

First things first – this is a pretty interesting little game. It does a lot with cardboard counters and a paper map simply by printing very large hexes that can each hold about as many counters as either side gets in the entire game. No zones of control, no counting terrain costs in order to move units.

Its been done before, but here it works very well.

The Next War in Lebanon was designed to show what could happen if Israel launched a second invasion of Lebanon with the goal of uprooting Hezbollah – a repeat of its 2006 attack but on a much larger scale.

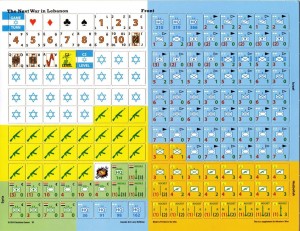

The game’s military units – infantry, vehicles and rockets – are two-sided, but the reverse side isn’t just a weakened version of the full-strength side. Troops on one side are concentrated for battle, on the other they are dispersed for defense.

Combat is automatic when opposing forces are in the same hex, but units that are disbursed can not be moved from one hex to another, while units which are concentrated can move but are not permitted to attack dispersed enemy units. There are some exceptions such as Israeli special operations attacks.

This all plays out in about two dozen areas – mostly hexes – which have just three categories of terrain: urban (significant cities), populated (many small villages and roads) and remote (poor roads, little population). Both sides (the Israelis and assorted Hezbollah, Syrian and Iranian forces) each get sanctuary hexes which the other side can not enter with land-based troops.

There is no limit to the number of stacks in a hex. But, there is definitely a limit on the actions that both side can take.

And, that turns out to be the most interesting part of the game.

Actions of any kind – movement, attack, searching or hiding units, reorganization, air strikes – take place after playing an appropriate command chit (J-1 to J-4) is played for the units involved. An optional advanced rule gives additional chits for planning and communications.

Each side has 24 chits to choose from, but they can only keep a few in their hand at any one time. That number is determined by the army’s command and control rating. The side with the higher rating also moves first.

As the game goes on, the Joint Operations chits become more important. A J-1 administrative chit can flip a disrupted unit (or re-load an Arab missile unit) while a J-2 intelligence chit lets you examine the units in an enemy stack or try and avoid an enemy attack.

The J-3 chits let you move a unit that is in combat mode, bring in reinforcements or spring an ambush. The moving player can also eliminate any possibility of an ambush if he plays two J-3 chits at the start of movement.

And, there are lots of other things to do with your chits. Too bad you can only do one of them. Welcome to cat-and-mouse land.

To make things even more exciting, combat actions may also lead to a cascading effect – one of more than a dozen different events, from Christiane Amanpour visiting the battlefield that causes the Israeli player to either gain or lose one of their action chits to the United Nations imposing a cease-fire, which can end the game.

Now for the adventure part.

The Next War in Lebanon is actually a re-design by Brian Train of his “Third Lebanon War,” which was published in 2011. Or, from his perspective, its a re-design of his re-design, with several rules changes made by the publisher after he submitted it. In his on-line remarks, he makes it very clear that he does not approve of the changes, but can do nothing about them.

There were also changes in the number of game counters and their design and in the map (it went from all irregular areas to most areas fitting into a hex pattern), none of which pleased him..

Train points out he, like most other designers, lost control of the game once he submitted it. He did not have the final word on how his game was edited before it was published. So, he put his original redesign on line, letting people decide for themselves which version they like best.

Train points out he, like most other designers, lost control of the game once he submitted it. He did not have the final word on how his game was edited before it was published. So, he put his original redesign on line, letting people decide for themselves which version they like best.

In part of a conversation Train posted on his web site, a man states clearly that Train was shown the changes before the game was published, and that they were made by the company to simplify the game a bit and give it broader appeal.

Now when an individual is in conflict with a corporation, it will look a bit one-sided.

And, there is no small irony in this situation. Train has published more than two dozen games and enjoys looking at unequal forces in conflict – asymmetric situations where strong efforts to restore civil order can lead to an open rebellion, or where a seemingly weak and scattered force can overthrow an entrenched government.

Oddly, I can’t find a game by him on the French Revolution. I would love to see his take on the fall of Louis XVI.

But, back to Lebanon. I thought at first I would enjoy the game because it did a nice job in capturing part of the uneven Mideast conflict. And, I got to argue that his game gives Hezbollah a little too much power to avoid Israeli attacks, although reality may be proving me wrong.

Then, while I was still trying to figure out the best mix of command chits for the opposing sides, the game itself changed before my eyes, turning from a “what if” projection about a likely future conflict into a fantasy game.

Why fantasy? Because I can’t see a broken Syria deciding to send armed troops into Lebanon to support rebels who would likely turn those guns back on the Syrian government, such as it is. Or on the people fighting alongside them in the rag-tag coalition against the Islamic State.

Now all I have to do is read the newspapers for a few months and it may turn back into a “what if” game again. Or, maybe, into reality.

Meanwhile, I can compare the strength and organization of Train’s re-designed game to the new version that ran in Modern War 13. Or, if I want, to his original game.

I have to admit that, before my friend Ed gave me his copy of Next War in Lebanon, I was unfamiliar with Train. Or, more precisely, I may have played some of his games, but didn’t pay much attention to who had designed them.

That’s a situation that I have to correct. His work is refreshing and interesting, which really are two different things. And, I expect, I will have a lot of fun exploring.

It seems I may be starting a new adventure wrapped in a mystery wrapped in an on-line debate….nah, no one will ever pick that line up and quote me. Of that, at least, we can be sure.

Game Resources:

Original Rules to “The Next War in Lebanon”

Original Rules to “The Next War in Lebanon”

Hello Mitch, thank you for your kind words.

I’m glad you saw that enough of my original “Third Lebanon War” design had survived in the Decision Games version to make it an interesting exercise for you.

The basic armature of the design is the “Staff Card” system originally designed by Joe Miranda and introduced in his game “Bulge 20”, published in 2009.

I have taken the bones of that system and twisted them in some very different directions: one is The Scheldt Campaign, a contest between two “conventional” armies, and this game on a hypothetical Lebanon campaign.

I see you have read some of my blog entries about the game and the changes that were made to the design after I submitted it, without my knowledge or my approval.

I first saw them when I got my personal, subscriber copy.

I haven’t catalogued them but at a minimum, the movement and combat systems were completely changed, etc. – some of the changes are listed on the link to the BGG thread you linked to above.

As for being shown the changes, I was shown the big-hex map, which preserves most but not all of the adjacencies from my original irregular area map (hexes are just very regular irregular areas to me), and the counters, which seemed superficially similar to what I had sent in.

What I was not shown were the rules, which is where the critical changes were made and which nullified or even reversed the points I was trying to make in the original design, as well as introducing new errata and internal inconsistencies with the things they had added (see https://brtrain.wordpress.com/2014/08/25/next-war-in-lebanon-redux-rejoinder/ and https://boardgamegeek.com/forum/1514833/next-war-lebanon/rules).

I really hope you will take a look at the original design, which I am making available for free on my website at https://brtrain.wordpress.com/2014/08/10/next-war-in-lebanon-redux/ .

You can even use the hex map from the magazine edition; just ignore all the charts printed on it.

But you will have to make a new set of counters.

A proper paper version of the game may yet be put up for sale later this year or next, for those who don’t want the Print n’ play experience.

Yes, I have designed a lot of games on asymmetrical, guerrilla, irregular, whatever warfare (https://brtrain.wordpress.com/personal-ludography/) and perhaps you have played some of my games already without realizing it.

I have never designed anything on the French Revolution; I did do one game on the 1848 revolutions but by and large I restrict my designs to the 20th and 21st centuries.

You did raise the point about Syrian intervention.

In my designer’s notes (which they didn’t touch) at the end of the game rules, I explain that the game was inspired by a paper that was written in 2010.

The game was designed in 2010/2011, just before the Arab Spring started.

And if your friend also sent you the magazine that came with the game, the lead article in the issue is by me, about this topic, written at the end of 2012 and it does take in some of the then-current events in the Syrian Civil War.

Then of course the game comes out in the late summer of 2014, and a year later you get your copy… so yes, with the benefit of almost 5 years’ hindsight the notion of Syrian involvement is unlikely.

However, it’s quite easy to simply drop the Syrians out of the equation, and explore the problem without them… the original game had a mechanism where they might not get involved at all, I certainly designed the game from the beginning with that thought in mind.

Thanks again for playing and reviewing the game, and I hope you will give the original version a chance.

Brian

I will note here (and for whatever it’s worth) that the discussion about “versions” of the rules (as published versus as submitted) is really a non-sequitur because, insofar as the game works perfectly well as published, and insofar as the raw designer’s version has been made available as an alternative, these simply represent more choices available to players; i.e., if only it were always possible to have both a simpler rules version and a more complex rules version of the same game.

In other words, any player that prefers the less-complex version of the game (as published) vis-a-vis the more-involved raw version (as submitted) have both available to them. Other pedantic differences like the shaping of territories into large symmetrical hexagons as opposed to irregular polymorphic shapes are really beyond trivial, any reasonable person would agree.

There are also a whole host of other reality checks that are too numerous to mention (like the necessity to use some game pieces to provide the “deck of cards” which the original raw design required…since, of course, a deck of cards could not be included with the magazine game); This, for example, was indeed discussed with the designer during the design process (to wit, it would have been simpler and logistically easier to simply write up a die-roll chart to accomplish the same thing as a deck of cards), and so there is much more to the story to this particular game’s development than simply the “designer’s version” versus the “published version”.

But again, considering that both versions of the rules are easily available to any player and his particular preference, there’s no actual tangible issue here at all. The published version of the game is intentially simpler and more approachable (and not by a whole lot, actually) but it imparts the same exact presentation of the situation and scope as much as any wargame can as a simulation. So, in short, there has been no harm done by any definition. If anything, the game has been played more than it otherwise would have been.

Eric 🙂