World War I

By Kirk Uhlmann

Covering the Russian Revolution, Salonika, Naval Actions, East Africa, The Guns of August and Multi-player gaming problems.

World War I games face several tricky political and military situations that can sometimes involve many special rules or convoluted resolutions. There is a balance between being realistic and historically accurate, as well as not implementing key events in a way to give a player too much “insight” as to what may develop – or guide them because of hindsight. A previous article touched on details of U.S. entry, and here we’ll explore how Lamps deals with some other important aspects of the war.

World War I games face several tricky political and military situations that can sometimes involve many special rules or convoluted resolutions. There is a balance between being realistic and historically accurate, as well as not implementing key events in a way to give a player too much “insight” as to what may develop – or guide them because of hindsight. A previous article touched on details of U.S. entry, and here we’ll explore how Lamps deals with some other important aspects of the war.

RUSSIAN REVOLUTION

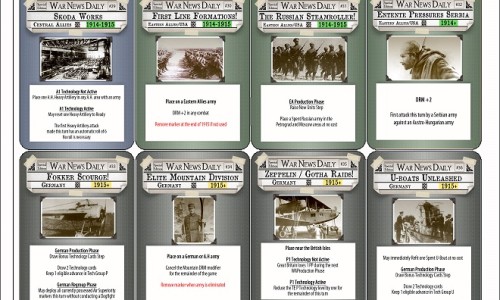

A difficult task WWI games face in addition to handling U.S. entry is how to deal with events in Russia, including the end of the Tsar and subsequent turmoil. U.S. entry was discussed previously and while there are several cards in the different faction decks relating to that, the Russian situation is more streamlined, while still maintaining historic realism. There are many significant events in Russian history in terms of the Revolution, removal of the Tsar, Bolscheviks taking over, the Civil War, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, and so forth. Having all of these represented individually as events would be both cumbersome from a game play perspective and also too much foreknowledge to the players about what events need to happen in what order for various consequences. Thus, in Lamps, the Russian political situation is represented with just three event cards: “Lenin/Bolscheviks Rise,” “Russian Revolution,” “Russian Civil War” and one marker with “Revolutionary Turmoil” on one side, and “Treaty of Brest-Litovsk” on the other. The first two trigger a Revolutionary Turmoil marker and set the stage for Russian collapse and the signing of the Treaty if the other card is drawn and Germany meets certain occupation requirements in Russia. Russian Civil War provides for immediate collapse depending on conditions or places the Revolutionary Turmoil marker to set the trigger for either of the other two cards. By using this interaction of the three cards, the proper odds and timing of events are set-up without having a complicated scripted sequence and without giving players exact knowledge of how many more increments of a multi-step process are required. These three cards provide for both the historic narrative as well as other possibilities in Russia and make sense since the events may be interpreted for different  ‘historic’ results depending on the time and order the cards were drawn. “Lenin/Bolscheviks Rise,” if drawn first, would refer to German assistance in supporting and getting Lenin back to Russia, whereas if drawn after “Russian Revolution,” would symbolize the funding and rise of the Bolscheviks in taking over from the post-Tsarist government. “Russian Revolution,” likewise, could represent either of the pair of revolutions – the removal of the Tsar if drawn first, or either the Tsar removal or Bolschevik revolution if drawn second. And, finally, “Russian Civil War” could refer to events leading up to and including the October Revolution or the civil war subsequent to the Bolschevik takeover. There are secondary effects to these cards as well depending on the situation or status of the marker. “Russian Revolution” impacts U.S. entry, as the removal of the Tsar provided an impetus for U.S. movement towards war, and if the U.S. is not in the war, the Bolschevik revolution and the political implications for Russia’s status in the war would also impact U.S. posture. If the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk is already in place, the Russian Civil War provides for a slight burden on U.S. production (if in the war) as resources are used to support the anti-communist elements. Likewise, the Civil War allows Germany to benefit with a slight production bonus due to their occupying forces and the chaotic infrastructure in Russia if the Treaty is in effect. All in all, the game’s representation of the Russian political situation is designed to be as streamlined as possible to enhance playability while still maintaining historic realism.

‘historic’ results depending on the time and order the cards were drawn. “Lenin/Bolscheviks Rise,” if drawn first, would refer to German assistance in supporting and getting Lenin back to Russia, whereas if drawn after “Russian Revolution,” would symbolize the funding and rise of the Bolscheviks in taking over from the post-Tsarist government. “Russian Revolution,” likewise, could represent either of the pair of revolutions – the removal of the Tsar if drawn first, or either the Tsar removal or Bolschevik revolution if drawn second. And, finally, “Russian Civil War” could refer to events leading up to and including the October Revolution or the civil war subsequent to the Bolschevik takeover. There are secondary effects to these cards as well depending on the situation or status of the marker. “Russian Revolution” impacts U.S. entry, as the removal of the Tsar provided an impetus for U.S. movement towards war, and if the U.S. is not in the war, the Bolschevik revolution and the political implications for Russia’s status in the war would also impact U.S. posture. If the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk is already in place, the Russian Civil War provides for a slight burden on U.S. production (if in the war) as resources are used to support the anti-communist elements. Likewise, the Civil War allows Germany to benefit with a slight production bonus due to their occupying forces and the chaotic infrastructure in Russia if the Treaty is in effect. All in all, the game’s representation of the Russian political situation is designed to be as streamlined as possible to enhance playability while still maintaining historic realism.

SALONIKA

While U.S. entry and the Russian Revolution are significant events all WWI games must grapple with, the political chaos in Greece is, in some ways, more complicated to represent even if the overall impact is not as great as U.S. or Russian events. One does not want numerous special rules to force a situation just for historic significance, nor can the effects of allied troops in Salonika be ignored. The foothold in the Balkans would be significant for the allies later in the war as well as potentially helping Serbia in the early stages. Event cards provide the opportunity for Salonika to be “open” to the placement of a Western Allied army, and it is up to the player to choose whether to exercise this option. However, the fall of Serbia or later events may “close” this chance and, if not taken advantage of, the Central Powers may have an easier time securing the Balkan front. There are limitations placed on this army in Greece (and only one is allowed unless Greece joins the war) and, if it is placed, it will have little impact for much of the war, but ultimately it is up to the Western Allies player to weigh the options of if or when to send an army there.

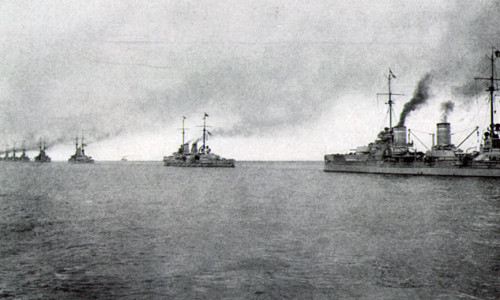

NAVAL ACTIONS

Much of the naval activity of the war is abstracted into the event cards and the effects of the British blockade on Germany. However, fleet units for both the Grand Fleet and High Seas Fleet are on the board and though the British naval units occupy the “blockade box” at the start, the German player does have the option to force a naval confrontation. Even if the German fleet is not completely successful, the British will be forced to expend resources to maintain and position their fleet, whereas the German player does not necessarily have to do so once they retreat back to port. Thus, opportunities can arise where the Germans have a viable strategy to send out their fleet and ideally force Britain to divert resources to the navy and not their land forces. On the other hand, a very successful German naval engagement could potentially break the blockade, which provides relief to Germany, even if Britain is later able to resume it. Britain must keep their fleet units fresh and in position to maintain the blockade, but since the German navies start fresh and may retreat back to port and remain in a spent status, the German player will usually have at least one opportunity to force a naval battle, and it is up to them to choose the optimal time. The naval combat system provides for naval units being made spent or eliminated entirely, but if both fleets engage with all units fresh (and Germany has received bonuses due to technology), the outcome will tend to the historic result – a tactical German victory but strategic defeat, i.e. Germany will have inflicted more damage than they received, but do not break the blockade. Other events in the game (Austro-Hungarian Fleets, East Asia Squadron) provide situations in which British fleets might be made spent and if not kept fresh, will provide an even greater temptation to Germany.

EAST AFRICA

The East African theatre is represented with its own track on the board. Like many of the peripheral fronts it was not of major strategic significance in and of itself, but the consequences of failure could have potential long term implications. The game situation for East Africa was designed to be a somewhat simple representation (the rules governing it to be in proportion to consequences of the front) while still providing for the history and key decision points and showing the drain of “sideshow” fronts to the main fronts. The British will have to decide how and when to allocate resources there to deal with the German forces led by Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, whose guerilla force has special attack capabilities. If the British have resources to spare, they might continually pour them into East Africa in order to eliminate the harassment or potential future worries of the German force, or they could procrastinate and only react to successful German advances – though this strategy might force the British to have to react when it is less convenient to do so. The British have more decision points in East Africa, but the German player has the key decision of when, or if, to make a full conventional attack on British forces to force the issue. The timing of such an attack would depend on the situation in the other fronts and also at what point in the war, since if Vorbeck is allowed to continue, his guerilla force will be able to be resupplied later in the war, thus giving him an opportunity to launch more probabilistically successful attacks, rather than harassing the British with lower odds (but free) guerilla attacks.

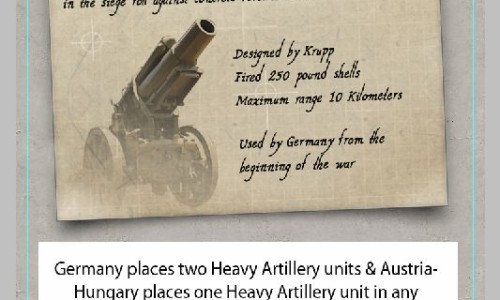

THE GUNS OF AUGUST

As the beginning of the game the Schlieffen Plan is firmly in place and the Germans are ready to unleash their offensive to the West. Certain event cards provide attack reroll bonuses but the Germans begin the game with two offensive rerolls available to them on the first turn to represent both the surprise of their attack and the quality and logistics of their training and mobilization. This allows the Germans to often times make their way through Belgium and into the Somme area, to the gates of Paris (though the historic result would indicate that their first roll of the game was a failure, and a reroll needed immediately as they overcame resistance in Belgium). Though the Germans can make it to Paris, mathematically they will not be able to take it on the first turn. This is consistent with the historic result but since the Germans almost made it, one might wonder if they shouldn’t have at least a chance on that first turn. The balance of the initial turn was set-up to give the Germans a good chance of solidifying themselves into the Somme area, though with poor rolls they can sometimes still be stuck in Belgium. Being able to take Paris on the first turn and an inevitable victory led to an unsatisfying experience, even if unlikely, where the game is essentially over after the first move of one player. Some aggressive German strategic movement, good die rolling, and poor planning on the part of the Western Allies may allow Paris to fall soon after and as the game turns are of somewhat indeterminate length (seasonal turns, approximately two to four months) this would still fall into a timeframe consistent with reality had the first Battle of the Marne gone differently or the Germans been able to successfully outflank the Western Allies in subsequent battles – occurring on the second game turn rather than the first. The range of possible outcomes for the Germans on their first turn will often set the tone and strategies for subsequent turns, from taking over the Somme (historic result) to not securing Belgium on the first turn (which makes it rough going for the Germans).

As the beginning of the game the Schlieffen Plan is firmly in place and the Germans are ready to unleash their offensive to the West. Certain event cards provide attack reroll bonuses but the Germans begin the game with two offensive rerolls available to them on the first turn to represent both the surprise of their attack and the quality and logistics of their training and mobilization. This allows the Germans to often times make their way through Belgium and into the Somme area, to the gates of Paris (though the historic result would indicate that their first roll of the game was a failure, and a reroll needed immediately as they overcame resistance in Belgium). Though the Germans can make it to Paris, mathematically they will not be able to take it on the first turn. This is consistent with the historic result but since the Germans almost made it, one might wonder if they shouldn’t have at least a chance on that first turn. The balance of the initial turn was set-up to give the Germans a good chance of solidifying themselves into the Somme area, though with poor rolls they can sometimes still be stuck in Belgium. Being able to take Paris on the first turn and an inevitable victory led to an unsatisfying experience, even if unlikely, where the game is essentially over after the first move of one player. Some aggressive German strategic movement, good die rolling, and poor planning on the part of the Western Allies may allow Paris to fall soon after and as the game turns are of somewhat indeterminate length (seasonal turns, approximately two to four months) this would still fall into a timeframe consistent with reality had the first Battle of the Marne gone differently or the Germans been able to successfully outflank the Western Allies in subsequent battles – occurring on the second game turn rather than the first. The range of possible outcomes for the Germans on their first turn will often set the tone and strategies for subsequent turns, from taking over the Somme (historic result) to not securing Belgium on the first turn (which makes it rough going for the Germans).

MULTIPLAYER

Lamps was essentially designed as a two player game, but due to the four factions taking their turns independently, becomes ideally suited as a three or four player game with no particular changes to the rules necessary. A four player game has the advantage of a more social setting as players may plan strategies together (or bicker) and is ideally suited for teaching new players the mechanics of the game before they take sole command in a two player contest. However, the Victory Conditions cover scenarios for a winning alliance only and there are no provisions for calculating independent faction victories vs. their ally.

Lamps was essentially designed as a two player game, but due to the four factions taking their turns independently, becomes ideally suited as a three or four player game with no particular changes to the rules necessary. A four player game has the advantage of a more social setting as players may plan strategies together (or bicker) and is ideally suited for teaching new players the mechanics of the game before they take sole command in a two player contest. However, the Victory Conditions cover scenarios for a winning alliance only and there are no provisions for calculating independent faction victories vs. their ally.

Game Resources:

The Lamps are Going Out: World War I will be published by Compass Games in 2Q16. Kirk Uhlmann is its designer, Hermann Luttmann is its developer and I was a playtester.

The Lamps are Going Out Playtest Components