The Race to the Sea

Review by Paul Comben:

The “Race to The Sea” is the name commonly given to the last gasp efforts by both sides in late 1914 to force a decision on the Western Front.

The “Race to The Sea” is the name commonly given to the last gasp efforts by both sides in late 1914 to force a decision on the Western Front.

Following the German retreat from the Marne to the Aisne, and efforts by French and British forces to break the first trench positions established by the Germans, efforts switched to trying to find and exploit the respective open flanks hanging to the west. In time this led to the opposing armies shifting divisions to the active portions of the front, and extending their lines to the north as those same forces successfully slammed the door on every attempt to get on their flank and rear.

Success was to elude both sides – largely because neither side had any overwhelming advantage to bring to bear. After earlier campaigning, the armies were approaching the end of their tether; neither side had any clear numerical superiority, any notable logistical advantage, or any telling superiority in weaponry or method that might have made a difference. As a consequence, the effort to find a flank petered out at the Channel coast, whose key ports where still in French hands at the end of the year, whilst a not insignificant part of France and nearly all of Belgium was in German hands, and would remain so for the next four years.

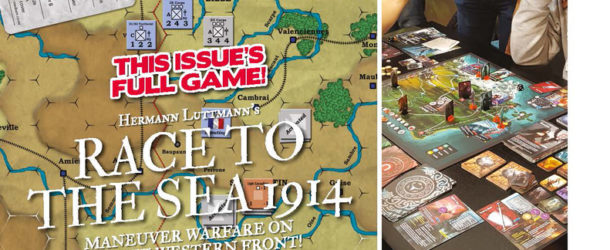

Hermann Luttmann’s design explores the possibility that things might have gone differently, had either side committed some fundamental error, or probably more by accident than design, just managed to muster a telling attack wherever the evolving opposition line could be unzipped.

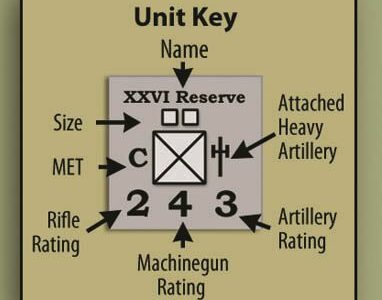

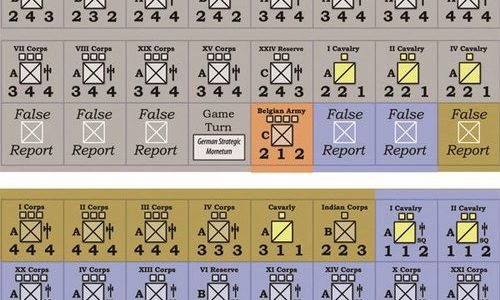

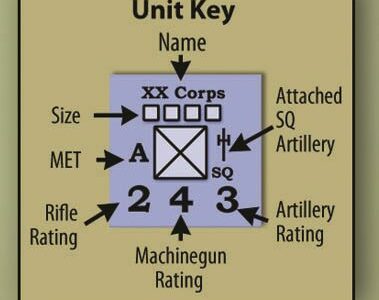

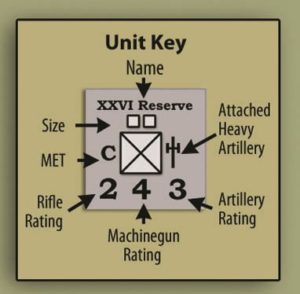

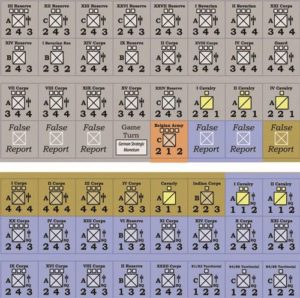

The game works at corps level, with each turn representing a period of about a week. The design philosophy, so it seems to me, is to work a lot of information and “happenings” into the unit counters and the various types of draw card the game comes with, and then let what is really a pretty straightforward system work its chaos, colour and unpredictability into the player’s experience.

Unlike the only other game I know of which specifically covers this campaign (Ted Raicer’s Clash of Giants II), this design places a great emphasis on narrative rather than just presenting a system. The Clash of Giants series never really appealed to me, largely because I indeed found it a bit on the bland side. By contrast, the units in RtTS are profiled for an overall level of unit quality/function, plus rifle, machine gun and artillery strength. These aspects are complimented by a range of random events, and a combat process that is both diceless and brings a number of the aforementioned factors into play via a simple card draw resolution process.

But before we get to who attacks what, a massive element of the game is found in its impulse system linked to a fog of war mechanism that is integral to the whole concept.

Units in this game will spend a great deal of time “the wrong (foggy) way up,” and their identity can only be discovered by their enemies via the combat process (not ideal), or by an effective use of cavalry. None of this is complicated in terms of how it is implemented, but you do need to think about how you are going to best employ the few cavalry units you have. Overall, the fog of war system in this game reminded me of what one sees as far back as the SPI titles Lee Moves North and Wilderness Campaign. Cavalry acts as your eyes, revealing enemies it is next to, but it is certainly not your fists. It is not as weak as the cavalry in the aforementioned designs, but it is scarce, fragile, and you do not want to lose it. In fact, one alternative rule I would tentatively suggest is making cavalry impossible to replace given the time frame of the design – just to make sure you do not get too much into the habit of having it doing too much actual fighting.

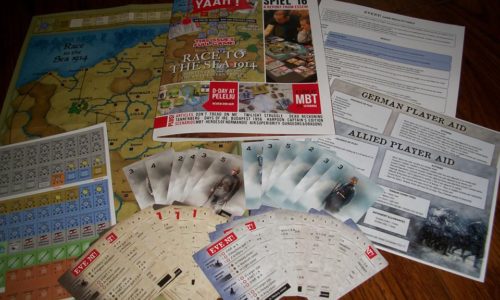

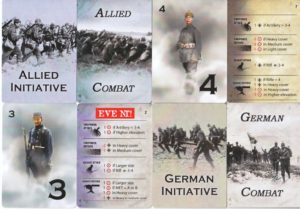

Going hand in glove with this is the impulse system, which is driven by players making bids from a small deck of cards. These card decks are nicely illustrated with depictions of soldiers of the era, but the working bit is a number which may permit you to win the bid (higher number), and then get an amount of activations in the current round equal to the difference between the winning score and the losing total. The numbers on the cards range from a high of six to a low of two, with a greater presence of cards valued at three. If both players bid the same value, the front is deemed temporarily paused, and the side with initiative gets just the one activation before the bid process is commenced again.

Frankly, I do not see how you can do a campaign like RtTS without some kind of staggering along these lines, as any “pure” Igo/Ugo system wherein everyone can move everything they have in one shift will not create the feeling-out and the haphazard push and shove that was a hallmark of this campaign. Certainly, part of mastering this system is getting a feel for the front tensions, and alongside acquainting yourself with the play inclinations of your opponent, knowing when to play your best value cards as well as the lesser values. In this context one should not assume that playing a two card is some sort of lesser option, as it all depends on the context. If you are pretty well set up on the map, there is nothing wrong with “forcing” or “encouraging” your opponent to find things to do by playing a low value card in expectation of Hans or Henri playing a larger value; and if Hans or Henri gets it wrong, playing your five or six card later may enable you to hit effectively against an overextended foe.

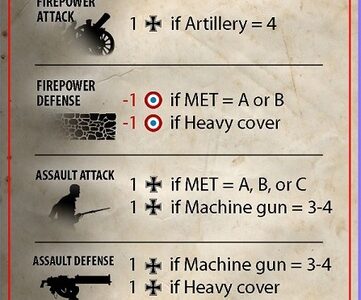

Combat resolution simply works around both sides drawing a combat card. However, combat itself comes in three different types:

Firepower Combat – This can be seen as your “spoiler.” This combat form will not gain ground, but it might prepare your forces to gain ground, or, if timed well, it can disjoint an enemy who is massing forces against one particular location.

Assault Combat – This is the ground gainer, but remember it is 1914, and so everything within that on-map narrative is likely to be clumsily performed and depending on sheer weight to effect anything.

Planned Operations – Only the side with initiative can try this; you place the marker on the map (somewhere important and somewhere the enemy would not like to lose) and then, when you are ready, conduct a bigger, more violent assault.

When you need to draw a combat card, you will look at the relevant portion for the combat type, and then check what factors the card determines to be relevant to creating losses – presence of heavy artillery in your units, their quality rating, how much of any one combat aspect you possess etc. Terrain can come into play to help the side currently on the receiving end, and this is where I have one of my small issues with how the design operates.

Hermann Luttmann went down the ready path of “Town equals some cover; city equals more cover than a town.” I do not agree with this in a 1914 context, just as The Gamers’ CWB system conferred no defender advantage for sitting in a woods hex (the concept being it made things more difficult to control given the stand close and blast tactics of the day rather than facilitating any defence benefit).

If one thinks of the actual story of battle around Ypres in 1914, the British got absolutely no material advantage for being “in the hex.” If anything, defending a pokey position for what amounted to matters of honour made them even more vulnerable, not less so. And “honour” I think is key to this; whether in the game context, it is Ypres, or Arras or Lille or Calais, the Entente forces especially are prone to a mindset of defending a position not for what it might give them in battle, but simply because it is a part of La Belle France or Brave Little Belgium. Certainly, if, as seems distinctly possible, this design does go to an expanded, boxed edition, a change like this is something I would love to see – a compulsion to defend somewhere you would really be better off in many cases leaving well alone.

Another area for improvement, although in its original form we are dealing with the realities of a magazine, small budget design, is having a larger number of combat cards. As things stand, both sides only have twelve each to draw from, and thus, inevitably, issues of card counting may come into play. Personally, I can never be bothered counting cards – it is like appreciating a piece of music more for how many notes are in it rather than what those notes are doing. But some players will see card counting as a legitimate part of good gaming, and so, both for the greater colour of the game and to make a 1914 experience rather more than recalling what you pulled out the pile last time, more cards would help.

So how do you win? Destroying enemies and grabbing key pieces of territory is important, but again, in seeking to create something with measurable notions of success, I feel the design strays just a little. The main aspect of this is the process of seeing, at game end, where your forces are in relationship to where the historical front actually was. If the French/British/Belgians have anything to the east of that line, they will benefit; likewise, if the Germans are to the west anywhere, they will be helped towards a level of success.

Personally, I think this needs a bit of nuancing. Simply standing in this or that muddy field a bit further one way or the other than the historical forces were in late November 1914 means nothing to me. It starts to mean something if, in addition to having a given quantity of your units to the west or east, you also have control of this or that city, or this or that stretch of railway. Those kind of considerations will build into a coherent picture of winning and losing, rather than finding “a better ‘ole to go to” in this field rather than that.

But this is still, at least for me, a far better recreation of the challenges of late campaigning in 1914 than Clash of Giants II…or I. You have events to work with, a dead easy but highly effective fog of war system to offer a further challenge; furthermore, the order of battle for both sides is full of character – good units, indifferent units, Prussian Guards, the Old Contemptibles ready to do something nasty (and rhyming) to Von Kluck, and at the last gasp, the students of the Kindermord keen to sacrifice blood and commonsense for the Fatherland.

As it stands, the game is replete with random elements – who has drawn what card to get things going; whose plans will be assisted or wrecked by random events; where the flip is the main enemy anyway? Great stuff. The game system offers temptation – will you overreach in that race to somewhere prestigious; will you feel compelled to get your cavalry dismounted just to grab something you really really want; and when, sometime, the siege of Antwerp ends, can you get the Belgians into the Entente lines or will you, as the Hun, catch and annihilate their defiant little army?

So, we have a very fine system that, overall, does a very good job with the subject matter. I personally think a little fine tuning would make things even better, but as things stand, for a small game operating at a fairly large scale, there is an awful lot going on.

Nice effort.

Paul Comben.

Game Resources:

“Race to the Sea” BGG page

“Race to the Sea” Living Rules

“Race to the Sea” Home page

“Race to the Sea” Home page

I agree with this review by and large, but what can’t be emphasized enough is the experience of the game dynamics in face to face play. Is your opponent going to respond to your move or does he have something else in mind? When do you play your high action card? What card did your opponent randomly throw down to create the action discard pile? Where are his dummy (false report) units? Highly entertaining stuff.