The Lamps Are Going Out: World War I

By Kirk Uhlmann:

Combat in “Lamps.”

Having previously discussed some of the background of The Lamps are Going Out, this article will illustrate details of its combat system. It’s an attritional based ‘bloodless’ system where units may be reduced from ‘fresh’ to ‘spent,’ but not directly eliminated as a result of combat (though they can be permanently eliminated if they are forced to retreat but have no friendly territory in which to go).

Having previously discussed some of the background of The Lamps are Going Out, this article will illustrate details of its combat system. It’s an attritional based ‘bloodless’ system where units may be reduced from ‘fresh’ to ‘spent,’ but not directly eliminated as a result of combat (though they can be permanently eliminated if they are forced to retreat but have no friendly territory in which to go).

Production points are used to restore a spent unit to fresh status and only fresh units may attack. Essentially combat depletes the resources of both sides as they feed additional supply and manpower (represented by the production points) to replenish their units. The major combatants are able to field a number of army units that is greater than the number of production points available, so choosing how to allocate the production, how many attacks to make, etc. is a key strategy in the game, as it was in the war.

As only fresh units may attack, so called ‘spoiling attacks’ become an effective strategy in that it reduces the offensive options of your opponent on their turn. If you can spare some resources to make an attack in an area, even with no hope of overrunning it, your opponent will not be able to organize a large offensive against you immediately – assuming your attacks are successful in depleting enemy armies.

Production points may not be saved from turn to turn, and so players are encouraged to use what they have available, either in attacks, mobilization, research, etc. This inability to save points reflects two aspects that benefit both gameplay and the historic reality. Armies are expensive to field and maintain, and the wastage of points by non-use both encourages the armies to be used and reflects the practical offensive-oriented mindsets of many of their leaders. There are no rules in the game for mandatory attacks or offenses – such requirements aren’t needed. If you have armies and resources available, it would be illogical from the game perspective not to use them in some way, just as the leaders at the time were not going to sit by and do nothing for long periods – they would try to gain any edge they could through tactics or technology in an attempt to turn the tide towards themselves.

The initial German strategy with Verdun – to deplete French forces faster than they can be replaced (either because of or in addition to the psychological effect) – is a key aspect of the game that is realistically depicted through the combat and production system. Just as the Russians wanted an offensive in the West to take pressure off of them and the British would attempt to deal with secondary fronts elsewhere in the world, the core strategy of the game is to plan your resources, offenses, and army deployments to force an advantage somewhere – either for direct gain on that front or to force resources of your opponent to be diverted there potentially weakening them elsewhere.

Ideally, through proper strategic planning and successful attacks, one can force a situation where the opponent cannot comfortably defend everywhere and then the advantage is pressed. The planning and effects are realized over several turns, and players must be able to react and adjust their plans accordingly depending on the actions of their opponent and the successes (or failures) on the battlefield. Like using a single piece to threaten two opposing pieces in Chess, one must position their forces and use of attacks and resources optimally so that one’s opponent cannot react everywhere at once, and ideally achieve a significant breakthrough. The leaders at the time were very much aware of these concepts and as the various fronts bogged down, looked at ways to advantageously use their resources to force their opponent into a disadvantage somewhere.

Ideally, through proper strategic planning and successful attacks, one can force a situation where the opponent cannot comfortably defend everywhere and then the advantage is pressed. The planning and effects are realized over several turns, and players must be able to react and adjust their plans accordingly depending on the actions of their opponent and the successes (or failures) on the battlefield. Like using a single piece to threaten two opposing pieces in Chess, one must position their forces and use of attacks and resources optimally so that one’s opponent cannot react everywhere at once, and ideally achieve a significant breakthrough. The leaders at the time were very much aware of these concepts and as the various fronts bogged down, looked at ways to advantageously use their resources to force their opponent into a disadvantage somewhere.

Proposed basic German army counter for Lamps – The quality of various countries armed forces is differentiated through the “technology” they control.

The army units in the game abstractly represent all aspects of combat arms, from the artillery that was so critical in the war, the infantry, aerial units, to even the combat support personnel – so each army unit is a significant self-sufficient fighting force capable of mounting offenses or defenses. In the combat system, attacks of such army units are individually resolved. So an area may have multiple armies that make attacks on a turn, some successful and some not, and likewise by the opponent. This represents the back and forth nature of the war and while the area based map contains territory somewhat sizeable, the effects of these battles results in a representation of the sometimes changing (though not strategically significant) local front lines not represented at the game’s resolution.

Attacks are resolved by having the current phasing player simply declare that a fresh army in one area is making an attack into an adjacent area and a subsequent die roll by each player. As strategic movement occurs before the attack phase, and armies must be fresh in order to attack, players need not deal with any complications or restrictions in terms of which units have moved or attacked. For the most part, the board at any time ‘speaks for itself’ and if there is currently a fresh army, it is eligible to attack. It is up to the player to decide where and how many attacks to make.

While they could attack with every fresh army they have available, it would usually not be prudent to do so as they could not all be adequately resupplied immediately. On the other hand, a player might forego many attacks in order to mobilize new units and/or resupply formerly spent units in order to prepare for a large offensive later.

While a combat chart could have been constructed with just one player (the attacker) throwing dice and consulting it in order to resolve the battle, having each player roll a die (or in some cases multiple dice) provides many distinct advantages. First, having each player roll provides more interaction and direct involvement and also players may have options (from technology or event cards) on how to modify their roll. A chart to represent the various permutations of options and number of combatants would be quite cumbersome and difficult to memorize, whereas the basics of the combat system and how to resolve it is easily learned and after throwing their dice both players immediately know the result.

In the most basic combat, an initial attack into an area, both players roll one die. The attacking army is automatically made spent and a defending army is made spent if the attacker equals or exceeds the defender’s die roll. If an attack is successful and there are no remaining defending units available to be made spent, the defenders are forced to retreat. The attacker taking ties does not result in an overall advantage for the attacker, since it is automatically spent just in making the attempt and any non-zero chance of the defender not being depleted gives the defense the advantage. The initial attack is certainly the costliest in terms of material expenditures and casualties, and should this initial attack be successful, the attacker will receive a +1 bonus on subsequent attacks from the same area to the same area.

In the most basic combat, an initial attack into an area, both players roll one die. The attacking army is automatically made spent and a defending army is made spent if the attacker equals or exceeds the defender’s die roll. If an attack is successful and there are no remaining defending units available to be made spent, the defenders are forced to retreat. The attacker taking ties does not result in an overall advantage for the attacker, since it is automatically spent just in making the attempt and any non-zero chance of the defender not being depleted gives the defense the advantage. The initial attack is certainly the costliest in terms of material expenditures and casualties, and should this initial attack be successful, the attacker will receive a +1 bonus on subsequent attacks from the same area to the same area.

This bonus offsets the initial penalty for what would be (in most cases) a frontal assault and takes into consideration penetration of the defensive lines and possible flanking opportunities. Should the attack stall in subsequent rolls where a defender is not depleted, the bonus is lost and is only regained on a subsequent successful attack. The bonus is also lost if the phasing player chooses to make an attack from or to a different area and then returns to the original attack. Only immediate follow-up attacks receive the bonus (until lost by losing the combat).

Therefore, as the battle develops a player may have to reconsider his initial strategy, from pressing on to success, to abandoning the effort if things go poorly, with each individual attack (one roll) by a single army having either a 58% chance of depleting a defender or a 72% chance of depleting a defender (depending on whether the +1 bonus is in effect).

However, more armies in an area will give the attacker more opportunities to use the +1 bonus and so the average ‘to hit’ percentage for the group will rise. Three armies will have an average individual ‘to hit’ rate of 63% (the first attack at 58%, the second attack at either 58% or 72%, depending on whether the first attack was successful and so on). Ten armies making attacks will raise the individual ‘to hit’ average across all the armies close to 66%, as more of them will be rolling with a 72% chance of depleting a defender. As a result 3 attacks will deplete on average 1.89 defenders (.63 * 3) and 10 attacks will deplete on average 6.6 defenders (.66 * 10).

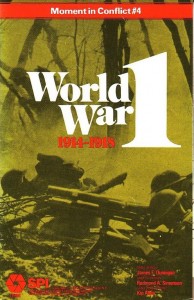

This translates nicely in that a 2-1 attacker advantage has a 42% chance of forcing a retreat whereas a 3-1 advantage gives them a 69% chance. One can then visualize combat as the defender tending to suffer two depleted units for every three attacking units (which would be depleted). If the combat were translated into a CRT, a result of 3/2 would be common (3 attacker to 2 defender casualties), and this is the case for the CRT that James Dunnigan uses in his classic game, World War I.

For Lamps, using comparative dice for combat allows a higher resolution of different results over the course of multiple attacks, allows for easy modifiers to be applied to either side (heavy artillery, aerial recon, poison gas, counter-battery, etc.) and has the added benefit of proportionally representing numerical advantages as the number of units on each side increases. At the strategic level, an attacker is more likely to dislodge a defending force at 9 vs. 3 rather than 3 vs. 1, and the iterative combat resolution (rolling for each attacking army) reflects this. From a game perspective, this makes large offenses rather interesting, even if the defenders are not dislodged. One’s initial strategy may plan on making a certain number of attacks into an area, but if initial rolls go better or worse than expected (and the bonus +1 is in effect – known as the “Big Push” modifier) they may be tempted to make “just one more attack.”

For Lamps, using comparative dice for combat allows a higher resolution of different results over the course of multiple attacks, allows for easy modifiers to be applied to either side (heavy artillery, aerial recon, poison gas, counter-battery, etc.) and has the added benefit of proportionally representing numerical advantages as the number of units on each side increases. At the strategic level, an attacker is more likely to dislodge a defending force at 9 vs. 3 rather than 3 vs. 1, and the iterative combat resolution (rolling for each attacking army) reflects this. From a game perspective, this makes large offenses rather interesting, even if the defenders are not dislodged. One’s initial strategy may plan on making a certain number of attacks into an area, but if initial rolls go better or worse than expected (and the bonus +1 is in effect – known as the “Big Push” modifier) they may be tempted to make “just one more attack.”

A future article will discuss more specifically how the various technologies are used to modify combat, along with the effects of trenches, aviation, and various event cards.

Game Resources:

Pre-order “Lamps” at Compass Games

Pre-order “Lamps” at Compass Games

Really happy to see this promising game move away from the wacky world of VPG, I would hate so see the designer’s and developer’s efforts be bizarrely twisted around (or even go to waste).

I see the game is for 1-4, are there many special rules for the solo player to follow?

The solo portion hasn’t been finalized as yet. The main game is going to blind testing shortly and things seem to be running on time for its 1Q16 launch.

Thanks for posting,

– Fred

Someone definitely has an axe to grind here… 🙁

Well, Kirk is the designer.