By Paul Comben

1914 – Things Suddenly Got Complicated

To put it in a nutshell, they (Avalon Hill) simply forgot about putting a game in the box. To put it bluntly, commercial appeal rolled off the glacis and into the moat with this one. To put it harshly, for all the colour in the components, the thing was as drab, out of time, out of synch and utterly depressing as those reels of monochrome silence showing ebullient crowds cheering their boys on their way to utter catastrophe.

To put it in a nutshell, they (Avalon Hill) simply forgot about putting a game in the box. To put it bluntly, commercial appeal rolled off the glacis and into the moat with this one. To put it harshly, for all the colour in the components, the thing was as drab, out of time, out of synch and utterly depressing as those reels of monochrome silence showing ebullient crowds cheering their boys on their way to utter catastrophe.

But here is the odd thing: assuming the original game had never existed in the past, if you proposed a new design today, covering the opening stages of the Great War on the Western Front, and featuring all kinds of detail from mobilization plans to step reduction to different kinds of artillery, and even a soupcon of unit movement keyed to the speed any given unit could move at, you would definitely get some attention within the hobby. But if you then produced 1914, with nothing more than a modern look given to those heretofore-dormant contents, expectation would give way to not a little despair.

I have gone back almost fifty years for this one, to a game with as much dust on it as most others of its vintage, because this is the one that presents the most quandaries as a low rated game, and because certain aspects of its design remain as points of contention in more than a few far more recent offerings.

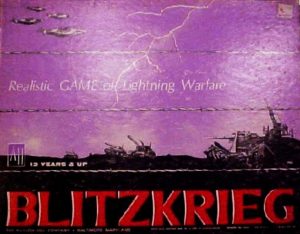

1914 was a big leap forward for the still relatively young Avalon Hill. It had very little in common with the “classics” that had preceded it, and a great deal of that was embodied in its striving for a level of simulation detail. Yes, Blitzkrieg (1965) had also striven for something beyond the norm, but fictional wars on fictional continents was never going to be the way to go – and speaking personally, it is an enduring puzzle to me why this system was not used to recreate the actual war in Europe it was clearly inspired by. A little after the publication of 1914, Avalon Hill also released Anzio – loved by its fans from very early on for its faithfulness to the subject matter, but the subject matter sidelined the game as far as the mainstream was concerned just as much as the campaign itself remained a sideshow when compared to grander events elsewhere.

1914 was a big leap forward for the still relatively young Avalon Hill. It had very little in common with the “classics” that had preceded it, and a great deal of that was embodied in its striving for a level of simulation detail. Yes, Blitzkrieg (1965) had also striven for something beyond the norm, but fictional wars on fictional continents was never going to be the way to go – and speaking personally, it is an enduring puzzle to me why this system was not used to recreate the actual war in Europe it was clearly inspired by. A little after the publication of 1914, Avalon Hill also released Anzio – loved by its fans from very early on for its faithfulness to the subject matter, but the subject matter sidelined the game as far as the mainstream was concerned just as much as the campaign itself remained a sideshow when compared to grander events elsewhere.

As for 1914, when it arrived in shops in 1968, it was by far the most complex board wargame on an historical subject – and not just by a little bit, but by one great leaping bound. Nothing else came remotely close; and what gamers, having thus far engaged with history via nothing more involved than Afrika Korps or Guadacanal, made of a system with no comfortable resemblance to anything else in the catalogue I can only guess at.

What is also important to bear in mind is that 1914 was not only a seriously complex game; it was also the hobby’s first step (I think) into the field of World War One land campaigns. Thereafter, for many years, further steps were pretty few and far between; and it is hard not to see 1914, a game that was in and out of the Avalon Hill catalogue rather quickly, as one of the major reasons why. The sad aspect of this is that so much thought had gone into ways of modeling the nature of those early Great War armies – the planning, movement, reconnaissance and fog-of-war, the susceptibility of fortifications to heavy artillery, the inherent superiority of the defender over the attacker; in all, an impressive list, but one entirely bereft of emotive appeal; stiff, dispassionate, process over atmosphere, yet oddly lacking those higher command representations that could have at least made it a more complete statement of what it was purportedly seeking to effect.

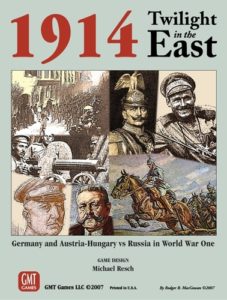

We can leap forward here to consider the most complex 1914-themed designs of today – the Mike Resch trilogy comprising Twilight in The East, Offensive à Outrance, and Serbien Muß Sterbien. One way to describe these works is as the marmite of the hobby (you either really like them, or do not want ever to go near them)[1]. Some veteran gamers I know find them virtually impenetrable; I, on the other hand, admire them a great deal. However, whilst, like 1914, they could be described as dry and heavily loaded towards the purely procedural side of the simulation genre, unlike 1914 there is a clear design philosophy evident that underpins the entire series. These are games with a strong emphasis on army management and military administration; that is what they concentrate on, and if that is not for you, then you are free to look elsewhere. But with 1914, the sum of all the parts was not really bound together by anything; it was, arguably, a whole mass of this and that, which, with everything included, verged on being impossible to play, and equally impossible to discern an overarching method to what was in the box.

We can leap forward here to consider the most complex 1914-themed designs of today – the Mike Resch trilogy comprising Twilight in The East, Offensive à Outrance, and Serbien Muß Sterbien. One way to describe these works is as the marmite of the hobby (you either really like them, or do not want ever to go near them)[1]. Some veteran gamers I know find them virtually impenetrable; I, on the other hand, admire them a great deal. However, whilst, like 1914, they could be described as dry and heavily loaded towards the purely procedural side of the simulation genre, unlike 1914 there is a clear design philosophy evident that underpins the entire series. These are games with a strong emphasis on army management and military administration; that is what they concentrate on, and if that is not for you, then you are free to look elsewhere. But with 1914, the sum of all the parts was not really bound together by anything; it was, arguably, a whole mass of this and that, which, with everything included, verged on being impossible to play, and equally impossible to discern an overarching method to what was in the box.

1914 did come with a basic game, which had a deceptively short set of rules, but in its own way, that was just a much of a chore to play as anything approaching the full-on version. Thus, when I look at many of the games I have owned, past and present, it seems no coincidence that those that have fallen short have done so, pretty often, by going too far. The irony is, that whilst we may think of game mechanisms as those things that enable a design to “move,” these same inclusions can all too easily create an inertia that stops anything moving that much at all. There is simply too much to move; too much to recall; too much to record; and human nature being what it is, too much either to get fed up with or totally muddled about.

One aspect of this, which has been an occasional feature for much of the hobby’s history, is game preparation. 1914 came with a pad of mobilization/planning sheets, upon which you were meant, at the very least, to plot the initial deployment of your forces; however, if you were going into the advanced rules, the same sheets were also meant to plot the movement of forces yet to be revealed on the actual mapboard – and that could be an awful lot of forces. The problems started with the sheets simply being too small to get everything neatly in place, and by the time you were moving units rather than just noting initial placements, the task became one hardly any gamer would relish.

1914 was not the first game to use such sheets to initiate the gaming process; the previous year, Jutland (itself an enduring model lesson as to the wisdom of rationing detail to suit scale), had come with sheets upon which you were meant to plot the initial moves of your fleet. This however, had simply meant drawing a few simple arrows on the map of the North Sea, each pertaining to the course of the task forces you had arranged. You did not have to cram the name of every ship into the course headings, or play around with superfluous details. The task force boards defined what ships were in which group, and the plotting process could be completed in a handful of minutes. But, being bereft of a conceptual philosophy, 1914’s plotting system was yet another feature of the game left to run amok – creating both a fiddly deployment process where everything had to be precisely located, and then seeping into a movement system that neither the game kit nor the game mechanisms were ideally suited for.

1914 was not the first game to use such sheets to initiate the gaming process; the previous year, Jutland (itself an enduring model lesson as to the wisdom of rationing detail to suit scale), had come with sheets upon which you were meant to plot the initial moves of your fleet. This however, had simply meant drawing a few simple arrows on the map of the North Sea, each pertaining to the course of the task forces you had arranged. You did not have to cram the name of every ship into the course headings, or play around with superfluous details. The task force boards defined what ships were in which group, and the plotting process could be completed in a handful of minutes. But, being bereft of a conceptual philosophy, 1914’s plotting system was yet another feature of the game left to run amok – creating both a fiddly deployment process where everything had to be precisely located, and then seeping into a movement system that neither the game kit nor the game mechanisms were ideally suited for.

Interestingly, although plotting/planning maps have never been a major feature within the hobby, they have stuck around, and are commonly linked to systems where a combination of fog-of-war and the desire to move units/formations in a historically realistic manner have been considered important. This has particularly applied to operational level air and naval games. From Luftwaffe to the likes of The Burning Blue and Bloody April, air games, where it is important to determine key aspects of a game situation prior to anything actually moving, and to hold players to what they have previously charted, everything will be presaged by a period of planning.[2]

Interestingly, although plotting/planning maps have never been a major feature within the hobby, they have stuck around, and are commonly linked to systems where a combination of fog-of-war and the desire to move units/formations in a historically realistic manner have been considered important. This has particularly applied to operational level air and naval games. From Luftwaffe to the likes of The Burning Blue and Bloody April, air games, where it is important to determine key aspects of a game situation prior to anything actually moving, and to hold players to what they have previously charted, everything will be presaged by a period of planning.[2]

What players think about this will largely depend on how the before and after of this aspect of simulation gaming marry together, and how taken any gamer is with the subject at hand. Some players might be ready to spend a considerable amount of time working things out on sheets if they love the subject and the game is seen as the indispensable work on the subject. In my experience, whilst many wargamers will give virtually any subject “a go,” the things that they love so much they will devote their attention entirely and absolutely to doing the thing totally correctly are probably rather few. Thus, there are plenty of gamers who will admire a game like The Burning Blue, and will be ready to see it as what is most likely is – the best (most accurate) Battle of Britain game out there. But it is rather unlikely that hordes of gamers are prowling around conventions looking for any and every chance to play it; there is a lot going on with this design, and a great deal of what is going on is not actually happening on the map.

One of the differences between a design like The Burning Blue and what came along with 1914, is that while The Burning Blue was not an introduction to a subject entirely new to the hobby, 1914 very much was. Before TBB gamers had had plenty of opportunity to see Battle of Britain games in all shapes and sizes, but 1914 had been preceded by absolutely nothing on the same theme. It thus acted, whatever its design team actually intended, as an introduction to the representation of the land campaigns of the First World War. In such a context, it was a bit like the boyfriend meeting his girl’s parents for the first time, and in doing so walking mud all over the carpet, knocking a fragile heirloom over, and dropping his coffee over the dog.

One of the differences between a design like The Burning Blue and what came along with 1914, is that while The Burning Blue was not an introduction to a subject entirely new to the hobby, 1914 very much was. Before TBB gamers had had plenty of opportunity to see Battle of Britain games in all shapes and sizes, but 1914 had been preceded by absolutely nothing on the same theme. It thus acted, whatever its design team actually intended, as an introduction to the representation of the land campaigns of the First World War. In such a context, it was a bit like the boyfriend meeting his girl’s parents for the first time, and in doing so walking mud all over the carpet, knocking a fragile heirloom over, and dropping his coffee over the dog.

In short, 1914 did not create any sort of clamour for a return visit involving more of the same. On the contrary, for years afterwards the land campaigns of the Great War remained peripheral subject matter within the hobby. It was not all bad news (I think of To The Green Fields Beyond and The Great War In The East), but overall the entire subject seemed as bogged down as a tank at Passchendaele.

And of course, heavy things do bog down – when they are indeed too weighty and too full of things; when they are too cumbersome and the territory they must traverse is not amenable. None of the concepts the game contained were bad ideas in themselves; they just needed a bit of sifting and a decent enough framework to house the most apposite of them. Fog-of-war is a vital part of many designs, and there are some very clever ways of making it work. 1914 wanted its fog, but chose an awful way of trying to make it work – not far short of trying to plot the movement of midges in a forest mist. One can compare this to the simple but brilliant use of fog-of-war in two early SPI titles – Lee Moves North and Wilderness Campaign. These games featured very little that one would consider essential for an ACW campaign game today, but they did feature that grasping for the unknown via flipped units and some very clever mechanisms for cavalry. This, in turn, created its own layers of complex decision-making, and left the player in no doubt what the chief premise of the design was.

And of course, heavy things do bog down – when they are indeed too weighty and too full of things; when they are too cumbersome and the territory they must traverse is not amenable. None of the concepts the game contained were bad ideas in themselves; they just needed a bit of sifting and a decent enough framework to house the most apposite of them. Fog-of-war is a vital part of many designs, and there are some very clever ways of making it work. 1914 wanted its fog, but chose an awful way of trying to make it work – not far short of trying to plot the movement of midges in a forest mist. One can compare this to the simple but brilliant use of fog-of-war in two early SPI titles – Lee Moves North and Wilderness Campaign. These games featured very little that one would consider essential for an ACW campaign game today, but they did feature that grasping for the unknown via flipped units and some very clever mechanisms for cavalry. This, in turn, created its own layers of complex decision-making, and left the player in no doubt what the chief premise of the design was.

After the infancy of the hobby, once games started to tailor anything to suit their given moment and its particular realities, things were bound to diverge from the pattern of the “classics”; and with that, there were going to be “firsts” for anything that smacked of being a new era/subject newly simulated. Some of these initiations, it must be said, fared rather better than others. There was nothing especially wrong with the first entries into the world of ancients, but they were hardly inspirational, and it took the hobby an awful long time to get cranked-up on quality products on ancient themes. By contrast, Panzerblitz, appearing just a couple of years after 1914, left gamers with their tongues hanging out. Yes, it had issues. Yes, it had flaws. But it was very playable, very game sexy, had serious cred, and the hobby was on a different level from that time on. And evidently, players wanted Panzerblitz and then Panzer Leader more than they wanted Tobruk, and today, the success of the Panzer series is testament to how much of an impression was made so very many years ago.

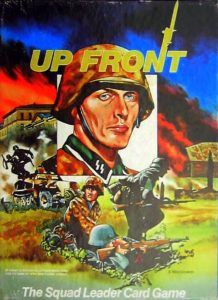

But there is never any guarantee that an original design with an aura of brilliance about it is going to usher in a bevy of marvelous things. Up Front was brilliant, but then, underappreciated in its day, it rather dwindled away with its nondescript expansions. The Ambush family was a great idea for a relatively brief while, but one that we are unlikely ever to see repeated in some new series. And rather more recently, Won By The Sword, intended as the herald for a whole new series of campaign games set around the Thirty Years War, fell foul of just about every conceivable slip-up in the development process. And those are just some of the perils; if you want more, well, companies can fold, be taken over or just decide to go in a different direction, leaving potential and promise looking for another berth before they become yesterday’s idea.

But there is never any guarantee that an original design with an aura of brilliance about it is going to usher in a bevy of marvelous things. Up Front was brilliant, but then, underappreciated in its day, it rather dwindled away with its nondescript expansions. The Ambush family was a great idea for a relatively brief while, but one that we are unlikely ever to see repeated in some new series. And rather more recently, Won By The Sword, intended as the herald for a whole new series of campaign games set around the Thirty Years War, fell foul of just about every conceivable slip-up in the development process. And those are just some of the perils; if you want more, well, companies can fold, be taken over or just decide to go in a different direction, leaving potential and promise looking for another berth before they become yesterday’s idea.

So how do we see 1914? Good idea badly developed? A fumbling, faltering attempt to be clever? An early spanner in the works of World War One gaming? All three? Or, fair enough, do you really like it the way it is? For me, it is an important design because it helped set simulation gaming off in a different direction and with aspiration to reach a higher level; and in that regard, whatever its shortcomings are perceived to be, I can only have the deepest admiration for the ambition that drove it along. That admiration certainly extends to how well presented the game was in the box; for, like the original version of Jutland, 1914 came with a glossy and substantial manual that aimed to do rather more than just put the rules in a certain format.

As I have said in an earlier article, the presentation certainly attracted the attention of my grandfather as the box sat next to me at the time of Christmas 1972. As a veteran of those same campaigns, he was not remotely put out that someone had made a “game” of his former fighting days; on the contrary, he was rather chuffed and clearly impressed by the look of the thing. And why not? The designer and his team had lavished a great deal of care on this work – I could tell that at thirteen; my grandfather could tell that at eighty. All that was really wrong was that I could not understand it!

Paul Comben

[1] Yeast spread served on toast – loved by some (like me), but keenly avoided by others!

[2] If you are want examples from ground-based games, perhaps the best examples are found in the Tactical Combat Series from The Gamers.