Waterloo: Enemy Mistakes

by Paul Comben

(Article produced from my own purchased copy.)

Waterloo: Enemy Mistakes is an Italian design that portrays the great battle of 1815 via what is essentially a miniatures system presented in a board wargame format. Whilst not a few designs over the years have adopted various aspects of miniatures for what are still fundamentally hex/area and counter wargames, W:EM goes a lot further, with the regulation of movement performed entirely by ruler, and the grouping of formations, and the arrangement of units in the combat process all derived from the world of miniatures gaming.

Waterloo: Enemy Mistakes is an Italian design that portrays the great battle of 1815 via what is essentially a miniatures system presented in a board wargame format. Whilst not a few designs over the years have adopted various aspects of miniatures for what are still fundamentally hex/area and counter wargames, W:EM goes a lot further, with the regulation of movement performed entirely by ruler, and the grouping of formations, and the arrangement of units in the combat process all derived from the world of miniatures gaming.

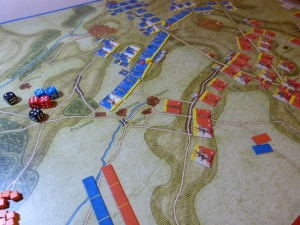

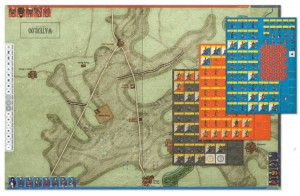

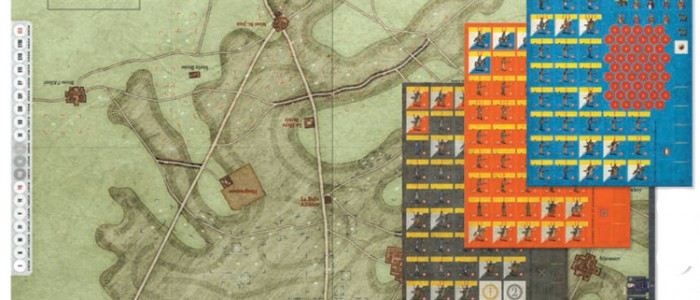

Physically, this is an attractive game, which, purely in terms of how it looks, really does entice the player into the battle world. The sizeable battlefield map comes in two parts, is mounted, and, at least to my eye, has a “miniatures” look about it – perhaps another way of saying that is that it is not the ordered, “choreographed” terrain, of the usual board wargame map. Personally, I would have preferred a slight 3d look to the various villages and bastions, but that is a small issue, and simply a matter of taste. Of rather more concern is the depiction of some other key battlefield aspects, especially the hills, whose definition and battlefield function have a certain want of clarity – something that goes beyond having no grid on the map whatsoever.

The units are mainly infantry/cavalry brigades, or key leaders, or groupings of artillery. There are also cardboard markers to denote losses, fired artillery, horse teams for artillery on the move, tokens for objective possession etc. The combat units have a certain similarity in size, look and quality to those you might find in the older Phalanx designs, and they are unobtrusively arranged with numerous pieces of information – a start location number, their ability to take damage, their fire discipline or lack thereof, an overall quality rating, a graphic of the uniform/troop type pertaining to the unit, and on the reverse side, the unit name and a victory point total for its loss. There are a small number of printing errors – Bylandt’s brigade is in a British uniform, and on their reverse side, the British Guards brigades have been identified as Saxe Weimar contingents. However, it is important to stress that all the working values are correct.

The units are mainly infantry/cavalry brigades, or key leaders, or groupings of artillery. There are also cardboard markers to denote losses, fired artillery, horse teams for artillery on the move, tokens for objective possession etc. The combat units have a certain similarity in size, look and quality to those you might find in the older Phalanx designs, and they are unobtrusively arranged with numerous pieces of information – a start location number, their ability to take damage, their fire discipline or lack thereof, an overall quality rating, a graphic of the uniform/troop type pertaining to the unit, and on the reverse side, the unit name and a victory point total for its loss. There are a small number of printing errors – Bylandt’s brigade is in a British uniform, and on their reverse side, the British Guards brigades have been identified as Saxe Weimar contingents. However, it is important to stress that all the working values are correct.

One riddle that it would be nice to have an answer to is the designating of several Anglo-Allied I Corps units as belonging Hill’s II Corps. Obviously, players will wonder if this is an error? In the absence of anything official, I think not. In the game, Hill is one of the most capable subordinate commanders, but left with his historic command, he is going to have very little to work with. I suspect, therefore, that the enlarging of his command was deliberate for the purposes of game function, especially looking at where he starts on the field; but that is purely a reasoned guess at this point, and nothing more.

The rules are in a full colour glossy booklet, which looks nice at first glance, but is seriously challenging once you start reading it. I should point out here that I ended up playing this game for nowhere near as long as I had planned to, and that was entirely because the rules were such an effort to get through. For what is meant to be a pretty straightforward game in terms of its mechanisms, I really did find this one of the most awkward sets of rules I have ever encountered. This was due to several reasons:

- The translation into English is lackluster at best, and in its worst passages, bewildering and frustrating. There are too many instances of the wrong word being used, with an inevitable slowing in comprehension of the overall set. To offer an example, the function of the game’s version of the French Grand Battery reads as follows: Until Units 23, 24 and 9 of the blue (French) army are in Formation together, they represent the Grand Battery. This, related to the actual game, makes no sense to me unless the “until” is changed to “While” or “As long as.” In other places, sentences become long-winded and difficult to pick apart – uses of “enemy” and “friendly” are hard to link to one side or the other, and do not help create any clear picture in the mind as to what is meant to be happening on the board.

- The rules are crying out for copious, and illustrated, examples of play – but there are none. There is meant to be a downloadable strategy guide, but I could not find it, though there were times I really could have done with some illustrations with text to connect some of the most vague and poorly translated material to something I could actually work through. The ironic thing is, my copy of the game (and I presume all others) includes two rulebooks, one of which is in Italian. To be fair to the team responsible for the design, perhaps collating the game this way was the only viable option, but if that was not the case, it does mean that I and many others have got a set of rules we will never use, when we could have had a handy strategy guide instead.

- The rules are littered with sidebars and boxed pieces of this and that, all in different font sizes and background colours – some are full of important game functions, whilst others are largely superfluous historical commentary. Navigating through these rules was very difficult – you cannot simply move top to bottom, left to right from page to page. Instead, you often need to divert to this or that box, or to what feels like random points around the rules, and this with no easy progression through the “game geography.”

- The one and only play aid is on the back of the rules, and is too cramped and crowded for comfort.

- Finally, there are far too many contingencies encountered in gameplay that are not catered for in the rules. The processes of game melees (which are actually any form of combat other than artillery bombardment), are riddled with issues pertaining to frontages, combat, pursuit and retreat assignments, but there is nothing in the rules to help you. Setting the game up and encountering actual situations can help you reach some workable conclusions as to what to do, but in my case a lot of this was simply yours truly “fudging” operations to keep the game going.

All of this can look bad, but I do want to stress that once I got playing, and that with a determination not to allow ambiguities to deter me from pressing on through the game turns, I did enjoy myself, and did feel that the basis of the system was pretty good and that two or three players could have an entertaining time playing through the battle. But it would all be markedly better if the rules were clear.

As I said a little earlier, my time to play this game ended up being shorter than what would have been desirable. To compensate for this, I played out a number of turns to cover, in my own way, the historical events of the French initial attack on Hougoumont, and the advance of d’Erlon’s corps against Wellington’s left. As these are events many of us feel familiar with, I thought they were good models to work illustrations of play around.

As I said a little earlier, my time to play this game ended up being shorter than what would have been desirable. To compensate for this, I played out a number of turns to cover, in my own way, the historical events of the French initial attack on Hougoumont, and the advance of d’Erlon’s corps against Wellington’s left. As these are events many of us feel familiar with, I thought they were good models to work illustrations of play around.

To get things moving in this design, and then to keep them moving, you need to issue orders. Wooden cubes/blocks of the relevant army colour (blue, red, black) represent a basic orders currency. This currency is distributed from the overall commander to his subordinates, and the subordinates then transform the raw currency into actual orders – Move/Keep in Movement/Recover from Shaken/Redeploy being the basic forms, with refinements added depending on what precisely you wish to do – like charge the enemy. At first sight, players could be forgiven for thinking that there are more cubes than any player is likely to need, but from turn 2 onwards, there is a process of initiative bidding, with players committing their choice of a wager in cubes to gaining the first “go” through all the steps of the ensuing turn – the bet cubes are then temporarily lost, although the winner (whoever bet the most) gets two cubes back.

I suspect there are various subtleties you can play with here. Both the French and the Anglo-Allies have some capable generals, who can generate some orders of their own (without requiring blocks to be dispensed their way). Other commanders are far less capable, and require constant battlefield “nursing.” Depending on the actual game situation (and there are too many of these to start citing any set examples), players might therefore just feel like gambling a lot of blocks because their better subordinates are already well set and stocked up. This might just cause the enemy player to over commit to wagers and starve their generals (especially the less capable ones) of order capacity. You might also be able to set up a “double turn,” going last in one turn and first in the next by playing your wagers cleverly. In the end, it will be up to the individual player to read the game situation and work out their play accordingly.

I suspect there are various subtleties you can play with here. Both the French and the Anglo-Allies have some capable generals, who can generate some orders of their own (without requiring blocks to be dispensed their way). Other commanders are far less capable, and require constant battlefield “nursing.” Depending on the actual game situation (and there are too many of these to start citing any set examples), players might therefore just feel like gambling a lot of blocks because their better subordinates are already well set and stocked up. This might just cause the enemy player to over commit to wagers and starve their generals (especially the less capable ones) of order capacity. You might also be able to set up a “double turn,” going last in one turn and first in the next by playing your wagers cleverly. In the end, it will be up to the individual player to read the game situation and work out their play accordingly.

Integral to getting the best out of the available orders is to understand the relationship between orders spent and those (the block/cube orders) a general may keep in hand from turn to turn. Each subordinate can keep no more than four such blocks at the end of a turn, so it is worth keeping in mind how many extra “orders” the general in question can generate for himself. This is important if you are attempting complex manoeuvres with sizeable formations. Without going into details, this sort of stuff will cost a lot of blocks – to get started, then to keep going, and also deal with damage and other contingencies along the way. If you empty out the store of someone like the Prince of Orange, who has all the military capacity of a small yapping dog, whilst trying to effect something major with him, you might well find him and his men utterly adrift with insufficient “currency” in the next turn to keep going, rally shaken units, and simply face the right way.

Integral to getting the best out of the available orders is to understand the relationship between orders spent and those (the block/cube orders) a general may keep in hand from turn to turn. Each subordinate can keep no more than four such blocks at the end of a turn, so it is worth keeping in mind how many extra “orders” the general in question can generate for himself. This is important if you are attempting complex manoeuvres with sizeable formations. Without going into details, this sort of stuff will cost a lot of blocks – to get started, then to keep going, and also deal with damage and other contingencies along the way. If you empty out the store of someone like the Prince of Orange, who has all the military capacity of a small yapping dog, whilst trying to effect something major with him, you might well find him and his men utterly adrift with insufficient “currency” in the next turn to keep going, rally shaken units, and simply face the right way.

No general can receive more than two blocks a turn, and as Prince Silly Billy cannot generate any himself, this is trouble ready to loom with overly incautious play. And even with better generals, it is still necessary to think at least a turn ahead to ensure that the order flow is going to be at least adequate for the jobs at hand.

Now, turning to my first W:EM battle, I began the engagement with the first bombardments. The French automatically have initiative this turn, and in my game the cannon opened up on an Anglo-Allied unit to the west of Hougoumont, and also on Bylandt’s exposed brigade further east. “Effective” range is found on the reverse of the measuring ruler (actually, it is the same length as the ruler), but there is no modification for range within that overall distance. In my game, this led, admittedly via some high dice rolls, to an assortment of units being struck early. I thought the artillery “hurt” was a bit on the strong side, and I was minded to recall the “windage” measure highlighted on a vintage British wargaming television series (Battleground) and given a YouTube link via The Boardgaming Way. This nifty device caught a sense of the spread of shot at longer ranges, and I would recommend creating something of the like for play of this game – actually, something along the lines of a specifically marked ruler and protractor would do the job, just to ascertain if you hit anything at distance or just see shots fall in the mud.

By and large, artillery in the game is perhaps more likely to create shaken results (units marked with yellow cubes) and drive units back somewhat rather than create actual losses – and note here, that all forms of combat are modifier heavy. Step losses only really occur at the higher end of results. Whilst marked with the yellow “Shaken” cubes, a unit’s capacities are diminished.

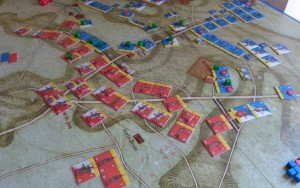

With no wagering for initiative this first turn, I thought it might be a good idea to load up every general on the map with a couple of blocks, just to cover contingencies and take advantage of what I think the rules permit you to do. Then, imagining the bands playing some French martial air, I sent Jerome’s division forward. As a big three-unit formation (formations are denoted by units touching at some point along their peripheries), Jerome needed three orders – so no problem, as I had two blocks sitting with Reille, the Corps commander, plus Reille himself can generate two orders. One unit got a bit slowed in the Hougoumont grounds, whilst another kept in line with the third, which went for the chateau garrison. That led to a melee with one unit directly attacking the chateau whilst the other two offered a support die roll modifier to the ensuing combat resolution. Now I must admit that at this point I cheated a bit, simply because I sent Reille forward attached to the attacking unit and got him killed. Not good. Formations/Corps without leaders able to issue orders appear to be utterly hapless and headless, and it can take time to get a replacement up and running. So avoid! To keep my game going as a try-out, I resurrected Reille and put him back where he should be.

With no wagering for initiative this first turn, I thought it might be a good idea to load up every general on the map with a couple of blocks, just to cover contingencies and take advantage of what I think the rules permit you to do. Then, imagining the bands playing some French martial air, I sent Jerome’s division forward. As a big three-unit formation (formations are denoted by units touching at some point along their peripheries), Jerome needed three orders – so no problem, as I had two blocks sitting with Reille, the Corps commander, plus Reille himself can generate two orders. One unit got a bit slowed in the Hougoumont grounds, whilst another kept in line with the third, which went for the chateau garrison. That led to a melee with one unit directly attacking the chateau whilst the other two offered a support die roll modifier to the ensuing combat resolution. Now I must admit that at this point I cheated a bit, simply because I sent Reille forward attached to the attacking unit and got him killed. Not good. Formations/Corps without leaders able to issue orders appear to be utterly hapless and headless, and it can take time to get a replacement up and running. So avoid! To keep my game going as a try-out, I resurrected Reille and put him back where he should be.

The strength of the key garrisons (Hougomont and La Haye Sainte) lies in their ability to ignore many adverse combat results, but as the French, it is always a lure to go after at least one of these locations as the victory points are big and some scenarios really do require that they are taken.

Meanwhile, the Anglo-Allies, moving up second, brought Picton’s leader unit and Lambert’s brigade closer to Pack’s unit. Bylandt, through bombardment effects, was already a mess with nowhere to go. One of Hill’s units moved to help bolster the Anglo-Allied right, but with little else really needing to be done so early, that was it. Wellington’s guns thundered back at the French with surprising effectiveness – too much effectiveness for my liking – and here I might also refer to the Line of Sight rules. As written, simply being on a hill seems to be the key to seeing everything everywhere, and as there are only two elements I could call hills on the map, it is not a rule I feel happy with. Commonsense can compensate for ambiguities, and for what it is worth, I play it that an intervening unit and any other blocking object will actually prevent line of sight if it is on the same level as either the attacker or defender.

When it came to launching d’Erlon forward, there were some interesting game insights. As I have already intimated, moving four divisions of infantry forward takes some saving up of orders (you need an impossible eight to move four, two-unit division formations, whilst, by my reading d’Erlon can only manage a total of seven – four already “in the bank,” two more given on that turn, and the one he generates himself). If you were to advance all the infantry as one formation (all linked/joined together in one line, the maximum cost is reduced to five orders, but you will likely have one unwieldy mass on your hands. But whatever you try, if you do empty the I Corps’ bank, keeping all the men moving and closing and rallying is going to be near impossible. The situation is eased if you employ the optional rule which puts Ney on the map and then has him act as a sort of battle group commander – he has to be fed orders, but he can command just about anything and so help keep an attack moving. But in all probability, to play a major assault well, you are going to have to employ a necessary amount of restraint, keep something in the bank to tidy the ranks and deal with contingencies.

When my French infantry closed, a number of game positives and negatives disclosed themselves. On the positive side of things, there are a number of apposite and clever modifiers baked into the combat resolution system (including for any pursuit), and frankly, as I hope my photos show, this game looks wonderful as the action unfolds. But the English language descriptions you need to work with are very awkward in places, and with obvious contingencies not covered, and without gameplay examples, I just had to extemporize.

When my French infantry closed, a number of game positives and negatives disclosed themselves. On the positive side of things, there are a number of apposite and clever modifiers baked into the combat resolution system (including for any pursuit), and frankly, as I hope my photos show, this game looks wonderful as the action unfolds. But the English language descriptions you need to work with are very awkward in places, and with obvious contingencies not covered, and without gameplay examples, I just had to extemporize.

Nevertheless, I found out a few more interesting characteristics of the system – such as attacking with just one unit in any given combat being usually a rather bad idea. What happens is that all the tangle of the post combat (two “order resistant” orange recovery markers) gets visited on the one unit, and it will take two turns to get them cleared away. Take a larger formation, with some forces in support of a point unit, and the hurt gets swept away in one turn, with two receiving units only having to remove one orange marker each. I also got “ambushed” by lurking modifiers when a single unit of French heavy cavalry sought to ride over some Anglo-Allied infantry. It did not work, because although there were some lovely qualities on that French cuirassier unit, there are some nasty modifiers on the melee table…that I had not noticed. Lesson – do not let cavalry charge infantry unless the infantry is shaken or in some other way combat unready. The squares are on that melee table, sure enough, even if they are not visible by marker on the board.

And that is as far as I got. I wanted to do more, but my time is limited right now, and it took so long to get the rules worked out. What I say by way of evaluating this design must be seen in this context – I wanted to give the game more time, but simply could not. To say the game needs more refining sounds like stating the obvious, but I am not only referring to the ambiguities in the rules, but also to matters like the capacities of the artillery and the nature of the victory conditions. In a three-player game, I think the Prussian player can win by himself, but I would not swear to that. But at the most basic level, winning by pure victory count, that is, without minimum qualifying levels, looks like inviting “gamey” approaches. Personally, I prefer victory assessments more closely linked to what that day in June 1815 was all about.

As for the Prussians, they have average generals and a fairly average army, but their numbers are everything. Incidentally, this design also has its own method of keeping the deploying Prussians where unrealistically alert French cannot get to them. In pursuit of that goal, there is a substantial “quarantine zone” along the eastern portions of the map that is for the Prussians to move on and no one else.

One question you could ask is whether I would buy this game again if I knew its rule issues? Speaking only for myself, yes I would buy it again. I love the look of the game, as well as some of the concepts that have gone into its form. Perhaps others would come to a different conclusion, but I do feel this is a diamond in the rough, that simply needed more of a polish and review before being launched. As it is, if the Strategy Guide does appear (at least where I can find it) and if we do get some examples of play which deal with the more complex situations this game is bound to throw up, then it would make a great deal of difference. And as is the case with not a few games, much depends on how well the game is supported post-publication by those who worked on it. If all else fails, I will try a few rules revisions myself, for personal consumption. And that, I think, is the best evaluation statement I can make.

One question you could ask is whether I would buy this game again if I knew its rule issues? Speaking only for myself, yes I would buy it again. I love the look of the game, as well as some of the concepts that have gone into its form. Perhaps others would come to a different conclusion, but I do feel this is a diamond in the rough, that simply needed more of a polish and review before being launched. As it is, if the Strategy Guide does appear (at least where I can find it) and if we do get some examples of play which deal with the more complex situations this game is bound to throw up, then it would make a great deal of difference. And as is the case with not a few games, much depends on how well the game is supported post-publication by those who worked on it. If all else fails, I will try a few rules revisions myself, for personal consumption. And that, I think, is the best evaluation statement I can make.

Game Resources:

Waterloo: Enemy Mistakes Home Page

Waterloo: Enemy Mistakes Home Page

Pendragon Games Studio Home Page

Dear Paul, thank you for the review.

As one of the producer of the game I would like to confront with you about this: since you seem very prepared, based on your review, I would like to ask you some questions/suggestions about the game.

You can contact me through email: info@sirchestercobblepot.com

Thank you in advance for your time.

Regards.

I passed your message on to Paul. If there is anything else I can do please drop me a note.

– Fred

Strategy guide is available now on the manufacturer’s website and runs to 31 pages. This may address some of the author’s issues, there seems to be quite a bit of information in it but saying that I haven’t read it thoroughly.

Now that the strategy guide is available, does this influence your view of the game? Is it worth the effort?

Hello there

The game’s Strategy Guide is, to my eye, a detailed, well illustrated glossary of the game’s mechanisms. As such it will probably help some pllayers with some play issues.

What it does not seem to be, again, if only to my eye, is an actual “strategy guide” . Alongside a few hints as to how to get the game rolling, a really well illustrated and annotated sample turn of play would have helped enormously.

The problem with the glossary is that it does not join the game functions together, but separates them by alphabetical order.

I suppose the logic of my answer is that I feel exactly the same about the game as I did before. I still have the same questions about certain functions and situations, but the game will not break if you make a house rule here or there to help the best the game has to offer. That is what I have done, because personally, there is enough here for me to engage with.

A YouTube film showing some play would be great, and after the amount of effort that clearly went into the design, it does seem a shame that the BGG page has been so quiet for so long.

Hi Paul,

I agree with all your comments and analysis, I have been discussing about the difficulties of this game since i bought it, now almost 2 years ago and more, and just recently I got the reply from the producers that the game was just an attempt and that SirChesterCobblepot and Pendragon will not support it further. Meaning, no video and no sample turns…

I think the only chance for this game to see the public it could deserve (because I am still not completely sure about it…) is that it goes on Kickstarter and gets streamlined with a decent rulebook and no self-supposed strategy-guide (which is just a glossary with some limited examples here and there) but a playbook or so.

Thanx anyway for your great post!

Best, Stefano

Hello Stefano

Considering the rather high physical quality of this game and the ambition of the system, I can only say that it came across to me as far more than “an attempt” and deserved the sort of support that a careful Q&A etc would have provided.

In my opinion, the problems the game had could all have been addressed by one or two dedicated documents you could download, as physically the game was as good as most things that arrive in the hobby – and most things that arrive in the hobby via one company or another, always need clarification here and there. I think this is part of the investment a design team needs to make in order to ensure that players can appreciate their work.

Paul

Having just purchased this game, following encouragement from a friend who wishes to play it with me, it is very galling to read that the game will not be supported further.

It looks wonderful and promises much. Then you start to read the rules and after hours of struggle seek help on-line, where you hope to discover help videos or an FAQ. I have found the Strategy Guide and will no doubt spend a lot of time reading that as well as the rules.

My willingness to invest so much time in getting to grips with the game is demonstration of just how much I want to play it – as Paul Comben did. To have a game that engenders such enthusiasm should be an opportunity to get it right for the future.

It seems unethical to take money from customers, knowing that there are problems with ever managing to play the game, which the manufacturer has no intention of solving. Very disappointing.

My best advice Adam, (which is not much), is just to fudge what does not seem clear, using common sense and whatever you can take from other systems to help you. Anything along those lines will probably not stray too far from the designers’ intent.

I have a second Waterloo game (Waterloo: Napoleon’s Last Battle) that uses a minis system on a board – that’s by the Spanish company Trafalgar Editions. I do a certain amount of support work for them, so I feel it is only fair to tell you that right now. But they have stuck by their product, supported it, always answer questions, and are due to bring out a second edition in due course.

As for this game, well it might say something that I have still kept it at home here. But surely one of the most frustrating and unnecessary examples of wasted potential I have seen in 45 years of gaming.