Feats of Ancient Times - Part II

By Paul Comben

Wargaming the Battles of Antiquity

I am going to begin the second part of this study by jumping more than fifteen hundred years out of the era we are meant to be looking at. Instead, just for a moment or two, I want to refer to that highly regarded series of  designs known collectively as The Great Campaigns of the American Civil War. In introducing this series, its author, Joe Balkoski, referred to a game (and a rather nifty one) he had designed a few years beforehand called Lee Versus Grant. That game as he admitted, had never quite been what he had wanted it to be, in terms of its overall mechanisms and scope. Therefore he had approached Civil War campaigns anew, had taken many of the concepts from the earlier game and worked them onto his new, broader canvas, and had thus given us Stonewall Jackson’s Way – along with all the other titles that followed in its wake.

designs known collectively as The Great Campaigns of the American Civil War. In introducing this series, its author, Joe Balkoski, referred to a game (and a rather nifty one) he had designed a few years beforehand called Lee Versus Grant. That game as he admitted, had never quite been what he had wanted it to be, in terms of its overall mechanisms and scope. Therefore he had approached Civil War campaigns anew, had taken many of the concepts from the earlier game and worked them onto his new, broader canvas, and had thus given us Stonewall Jackson’s Way – along with all the other titles that followed in its wake.

This touches on our theme in that, at least for a gamer like me, a major difference between the games of the opening decades of the hobby, and so much that we have seen in more recent years, lies in the ambition of the designer in the modern era to produce and tailor work specifically to suit a particular theme, period, age etc. much more than was the case in times gone by. There is no hard and fast division as to when it all changed, and certainly there were “concept” games and the beginnings of series way back in the day – the Richard Berg ACW Regimental Series goes back a long way, as does, of course, the La Bataille Series and the earliest forms of  Squad Leader. But, with these being concepts in their earliest forms, things were still far from settled; and clutches of related games that embodied a vision of how an era fought its battles, or how you made these battles easy to get into yet thoroughly entertaining, were yet to appear.

Squad Leader. But, with these being concepts in their earliest forms, things were still far from settled; and clutches of related games that embodied a vision of how an era fought its battles, or how you made these battles easy to get into yet thoroughly entertaining, were yet to appear.

Whilst I very much hope there will always be room in the hobby for the genuine “one-off” game, it can surely be no accident that ancient battles, along with many other themes, are largely represented these days by families or series of games rather than the old style of “one here and one there.” That is not to say that quite everything that comprises a series necessarily has a big concept or a philosophy behind it. Decision’s Battles of the Ancient World runs into several volumes, but I would be hard pressed to find any definitive vision of ancient warfare attached to it. By contrast, you may not need a series of titles if one work does the job intended – and here I am thinking of Philip Sabin’s Lost Battles. But whatever format the battles of antiquity are presented in today, in many respects it is all leaps and bounds ahead of much that was seen forty or more years ago; and really, there is no better place to start than with that massive presence with the hobby called The Great Battles of History.

GBoH – The Feat in Detail

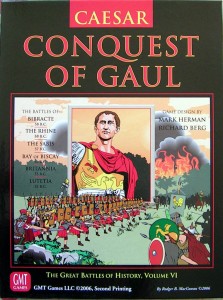

Within my own wargame collection I have a fair number of GBoH titles, but by no means all of them. Of course, a few of the games in that line are not relevant to this study, being way outside of the era in terms of subject matter. But with those I do own, and which are relevant to this piece, I can recreate battles over a period of more than two thousand years. By anyone’s measure, this is a massive chunk of time, and of course, we are also looking at action over a large slice of the globe and with a dazzling assortment of different armies. At its antique extremes, I can be with the forces of Sumer (via Chariots of Fire) twenty-three hundred years before the time of Caesar, and at the other end of the line on my shelf, I can be landing with Caesar on the coast of Britain (Conquest of Gaul). Geographically speaking, I can be as far west as the

Within my own wargame collection I have a fair number of GBoH titles, but by no means all of them. Of course, a few of the games in that line are not relevant to this study, being way outside of the era in terms of subject matter. But with those I do own, and which are relevant to this piece, I can recreate battles over a period of more than two thousand years. By anyone’s measure, this is a massive chunk of time, and of course, we are also looking at action over a large slice of the globe and with a dazzling assortment of different armies. At its antique extremes, I can be with the forces of Sumer (via Chariots of Fire) twenty-three hundred years before the time of Caesar, and at the other end of the line on my shelf, I can be landing with Caesar on the coast of Britain (Conquest of Gaul). Geographically speaking, I can be as far west as the  lands of the Cantii, or as far to the east as the domain of Chandragupta. The armies presented may all be readily defined as belonging to the pre-gunpowder age, but we are really dealing with a vast diversity of cultures and military concepts. Some of these cultures, and the armies they produced, are at least reasonably documented; others have drifted into snatches of verse, pictures on the side of potshards, and a remembrance drawn from regions perilously close to nothing and nowhere.

lands of the Cantii, or as far to the east as the domain of Chandragupta. The armies presented may all be readily defined as belonging to the pre-gunpowder age, but we are really dealing with a vast diversity of cultures and military concepts. Some of these cultures, and the armies they produced, are at least reasonably documented; others have drifted into snatches of verse, pictures on the side of potshards, and a remembrance drawn from regions perilously close to nothing and nowhere.

In Part One of this study, I offered some suggestions as to what might be gleaned of the practice of armies in the far long ago, but it is important to point out that the story of GBoH began with one of the best documented of ancient armies and commanders – the Greeks/Macedonians of Alexander the Great. Whatever the subsequent revisions seen in the different editions of Great Battles of Alexander, the model was clearly viable from early on, and with the initial hosts tested and quantified as to the constituent parts, there was an initial comparative reference for much that was to follow.

GBoH is often described as a complex game system (I am not doing “simple” GBoH here, to avoid muddying the waters, and having those waters turn into a lake), but at its heart are three straightforward concepts – quality of leadership, quality of unit, and effectiveness of weapon type. On the face of it, one might say that these apply to every era of warfare; but then again, they mean different things to those different eras. There was distance killing in the ancient world, but it was never much of a distance, and at Cannae, the slaughter of tens of thousands of compressed Romans was effected with a terrible intimacy. Suffering, pain, and the dynamics of morale, must likewise have their commonality of expression over eras, but there is difference also. In 1976, just to offer an aside, the late British actor Leo McKern narrated a BBC documentary to mark the sixtieth anniversary of the Battle of the Somme. By way of introduction, in these same fields of Picardy, McKern described the point and blade struggle of Agincourt as “A cockfight in a farmyard” in comparison to the ordeal of the Somme. There was valour on the Somme, but it tended to be dwarfed by the industrial processes of slaughter that often did not give your executioner a face. And there were no Alexanders or Caesars either; something that Patton as portrayed by George C Scott would surely have lamented.

GBoH is often described as a complex game system (I am not doing “simple” GBoH here, to avoid muddying the waters, and having those waters turn into a lake), but at its heart are three straightforward concepts – quality of leadership, quality of unit, and effectiveness of weapon type. On the face of it, one might say that these apply to every era of warfare; but then again, they mean different things to those different eras. There was distance killing in the ancient world, but it was never much of a distance, and at Cannae, the slaughter of tens of thousands of compressed Romans was effected with a terrible intimacy. Suffering, pain, and the dynamics of morale, must likewise have their commonality of expression over eras, but there is difference also. In 1976, just to offer an aside, the late British actor Leo McKern narrated a BBC documentary to mark the sixtieth anniversary of the Battle of the Somme. By way of introduction, in these same fields of Picardy, McKern described the point and blade struggle of Agincourt as “A cockfight in a farmyard” in comparison to the ordeal of the Somme. There was valour on the Somme, but it tended to be dwarfed by the industrial processes of slaughter that often did not give your executioner a face. And there were no Alexanders or Caesars either; something that Patton as portrayed by George C Scott would surely have lamented.

So, returning to antiquity, it should come as no surprise that GBoH, however immutable its basic concepts are, has nevertheless had to tailor its systems to suit particular times, armies and situations in order to present credible models of the given battles. That it intends to offer considerable detail, and works by detailed functions, inevitably means that some of the wheels and gears need changing from title to title. The quality of the subsequent fit for each game has inevitably varied somewhat. Opinions are bound to vary as to what has worked and what may have fallen short; all I can do is offer a look at a representative range of the designs and indicate the challenges posed by particular subject matter.

GBoH – The Fit of the Field

As I said in the first part of this article, our knowledge of the location and aspect of ancient battlefields varies considerably. Some, and only some, are well enough known that not only their location, but also their character as it would have been in a previous epoch, can be fairly deduced. Others, beyond a broad definition of regional peculiarities, are all but lost. But the GBoH series relies on detail and definition – and that applies to the given locations of units on the field, as well as what matter is presented on the actual units themselves. The battlefields of this series are a mixture of what nature put down or left behind, and what man has subsequently turned up with – be that habitations, bridges, or the array of contesting armies. Because of the nature of the maps, (hex grids intended to place this or that contingent precisely at a given point), the broad definitions of terrain have to be represented by features at precise locations, irrespective of whether there really was any such thing at the place in question. This is hardly much of an issue most of the time, but it is not the only way of doing a map.

Much more of an issue is how the map and the armies relate to each other. In all wargaming, I would strongly contest that there are few sights more stirring than seeing one of the GBoH “biggies” set up and ready for play. On the other hand, I would have to say that the series is also capable of producing some visual turn-offs, where uninspiring arrays of not very much do nothing at all to whet the appetite. This is an issue I will return to later, but just for now, I think it is worth introducing the argument that just about any system dedicated to a particular military theme is going to have its off-moments; that it will do some things very well, some things perfectly well…and some things, even if they are very much relevant to the subject matter, where you might want to go in another direction.

The maps of GBoH are, of course, more than presentations of a given site defined by known or assumed features – in other words you will interact with terrain rather than just having it there as a backdrop. Terrain will affect unit movement, a unit’s ability to hold together and still be effective, and will play its own part in the actual combat resolution process. This might sound pretty obvious stuff, but no other ancients system that I know of does this sort of thing so thoroughly. From title to title, the series takes a mighty look at more weapon and unit types than I can readily count up, and then assesses them for function in accordance with what terrain they are passing through or are presently situated in.

Ironically, we might find one of the best examples of how GBoH terrain can frustrate and impede an army via a battle that is not one of the series staples – it just makes the point rather succinctly. If we think of the Teutoburger Wald (the actual scenario is tucked away as one of the goodies of the GMT site) whereas other games will do plenty of right things – essentially hide the Germans and confuse and slow the Romans, the overall terrain nightmare facing the Romans here essentially degrades their fighting ability before the first German has emerged from his hidey hole spitting leaves and twigs – i.e. the modifiers for this and that are set against them; cohesion loss is more pronounced within the wild woods; they cannot move that well…and it is raining.

In short, in terms of teaching you something, the series makes it clear that one important aspect of command was finding the right battlefield to be on in the first place – one where your chariots are less likely to flip, where your cavalry has room to roam and to charge with gusto, and basically, where the exertion of battle is more likely to degrade your enemy than hurt yourself. One interesting aspect of GBoH is that only very rarely does the terrain on the map ever specifically relate to the determination of a winner and loser. In most cases, winning is by degrading an army to the point it breaks – terrain can help or hinder by bestowing or denying certain tactical advantages, perhaps linked to the best usages of your best units, but it is rarely and end in itself. offers the odd instance where capturing a location can end a battle, but it tends to be the exception rather than the rule. In all honesty, the battlefields of this long era were, in prevalent cases, much more to do with where armies bumped into each other, or sometimes (probably very rarely) agreed to meet, or where one or other side thought they could deploy with advantage (e.g. Issus and Gaugamela). Being right on top of something of absolutely vital national/strategic import that could not be lost was not that common – Vercingetorix was certainly important that way, but he was someone, not a something. I suspect that example of a  GBoH title with a difference, Caesar in Alexandria, might just have key geographical objectives (palace/quay/lighthouse etc.), though I would need someone to confirm that.

GBoH title with a difference, Caesar in Alexandria, might just have key geographical objectives (palace/quay/lighthouse etc.), though I would need someone to confirm that.

Although a little outside our terms of study, if you do own a fair number of titles belonging to this series, it might be an interesting exercise to ascertain which battles show a prepared or preferred field for either side, which favour one side or another by accident or design, and which are just where the armies more or less happened to meet up. The ratios produced by such an exercise would be another insight into the ways of war two to four thousand years ago.

GBoH – The Fit of the Armies

However philosophical we get about the enduring horrors of war, and especially in this era as to how they pertain to the realities of close-up execution, there is no getting away from the fact that there is a serious amount of difference between the first cohort of Caesar’s Tenth and what was pining for home and a sight of the ziggurats many centuries earlier…according to some scholars at least. On the other hand, although evidence of military practice in the “Sumer” era is hardly abundant, the little that does exist is both detailed and compelling…up to a point. Again, I might be accused here of wandering off subject, but this is fascinating material and does highlight some of the issues facing a designer at the more detailed end of the wargame spectrum. When it comes to a game like the problem arises as to which scholarly interpretation you go with when it comes to the practice of arms. Doyne Dawson, in his book The First Armies inclines to the belief that, to give one notable example, the armies of Sumer were essentially loose mobs of militia, incapable of most forms of sophisticated military evolution. By contrast, Professor Garrett Fagan (lecturer on ancient battles for the Great Courses series) is amongst others who assert that the archeological evidence of Sumerian stele and what is known as The Standard of Ur, can be trusted as faithful representations of those same forces in action as well as in appearance. What the stele and standard present is ordered troops, in formation, carrying effective weaponry (including bows) and being accompanied by wheeled battlewagons that are being hauled by wild asses.

When one adds the depiction of protective “accouterments” such a shields, helmets, and heavy garb adorned with metal discs, and these at least somewhat capable of mitigating some kind of blow, the notion that these forces were crude assemblages of toughs and impressed potters becomes rather open to question. That is further undermined by evidence from Sumerian royal tombs of the same era, which present a range of military artifacts strongly suggesting that warfare had already gone past the epoch of “brawls with blunt things.” However, in what is the opening scenario in Chariots of Fire, the designer, in the introductory notes, does not entirely dismiss that notion if I am reading him correctly. And on the other side of the coin, relying on art to tell you about war is not always a good idea. It may well be that whoever produced the Ur standard was as au fait with the practice of the soldiers he was presenting as a Don Troiani or Mort Künstler; on the other hand, he might have been drawing, at least partially, on the imaginative muses, in which case the standard might just belong with Turner’s depiction of Trafalgar, Lady Butler’s depiction of the Union Brigade at Waterloo, and many a film director’s depiction of war – in which case Doyne Dawson’s arguments will gain weight.

When one adds the depiction of protective “accouterments” such a shields, helmets, and heavy garb adorned with metal discs, and these at least somewhat capable of mitigating some kind of blow, the notion that these forces were crude assemblages of toughs and impressed potters becomes rather open to question. That is further undermined by evidence from Sumerian royal tombs of the same era, which present a range of military artifacts strongly suggesting that warfare had already gone past the epoch of “brawls with blunt things.” However, in what is the opening scenario in Chariots of Fire, the designer, in the introductory notes, does not entirely dismiss that notion if I am reading him correctly. And on the other side of the coin, relying on art to tell you about war is not always a good idea. It may well be that whoever produced the Ur standard was as au fait with the practice of the soldiers he was presenting as a Don Troiani or Mort Künstler; on the other hand, he might have been drawing, at least partially, on the imaginative muses, in which case the standard might just belong with Turner’s depiction of Trafalgar, Lady Butler’s depiction of the Union Brigade at Waterloo, and many a film director’s depiction of war – in which case Doyne Dawson’s arguments will gain weight.

There are other pitfalls as well. Logically, looking at what the warriors of a time or of a “nation” equipped themselves with, should suggest how they would prefer to align and fight – this is something I put forward in part one of this article. But again, logic is not always the best tool – the weapons of the western and northern European barbarians at the time of Rome’s supremacy strongly suggest that a bit of “swinging space” was necessary; but time and again, these same barbarians contributed to their own defeat by acting in ways that denied them the very space they needed. It is at this point that the deduction of military practice often needs more than a simple assessment of what gear is being carried or worn. Cultural and religious codes could play more than a small part in deciding who or what went where, and how battle was then expected to proceed.

Something else that can be introduced as a random factor is the notion of planning…or lack thereof. At some level, I find it difficult to believe that peoples capable of some sophisticated engineering and architecture, and had the sort of civic administration that could raise taxes and have people employed in non subsistence forms of activity, would invariably turn up on a battlefield and then “wing it.” This is an issue right across the series of games we are looking at, for in many cases the deployment of forces given pertains to a plan the commander in question intended to work to – the trouble is, some processes in some games can make it difficult to get any form of that plan into operation. This is not a factor all the time, as pre-battle planning varied so much, but if a plan is present but cannot so much a begin to be acted upon, there is something the matter.

All this feeds into issues as to whether systems really do allow us to work with our cardboard armies in some semblance of their actual practice. Within GBoH I think I am right in saying that there have been issues regarding the use of anything fitting the broad description of skirmishers in parts of the series. In C3i 15 there was an interesting reinterpretation by Dan Fournie regarding the capacities of such units in SPQR. At the very least, this article highlighted the challenge of seeking to model the units of antiquity, and whether any model can accurately capture everything. What I am leading to here is that even a system as dedicated to detail as GBoH cannot accommodate and present every battle equally well – and that opinions and interpretations on other issues are bound to vary. Special rules can always be added, but the series, or just about any other series, is inevitably going to be a prisoner of its scale and its fundamental mechanisms. I apologize for going back to Sumer yet again, but as it is the earliest battle in the series, it does have an important place in the overall reckoning. There appears to be a general historical consensus that the armies of the earliest period were small – how small is open to conjecture, but probably little more than five thousand would be a safe upper limit, although numbers may have been augmented by allies and some forms of mercenary “buying-in.” CoF shies away from the scale definitions of “one unit equals x amount of men,” probably in recognition of the difficulty in ascertaining how big or small these contingents were. Nevertheless, at least in my opinion, both here and in other titles, armies can look lost on the maps, and the process of battle can lack credibility and flavour as you are reduced to an overly detailed shoving match between miniscule or insipid armies. It is much the same with Hoplite: it is hard to say the game puts a foot wrong in terms of what it seeks to model in this era of Greek warfare, but the run and shove of smallish armies on featureless maps, although perfectly valid, makes less than inspiring gaming fare,,,at least for someone like myself.

This still largely leaves the question: What makes different armies in this series actually fight differently? In one sense the answer is all over the place, as no one aspect of the series carries the entirety of the response. If we think of most of the barbarians in CoG for example, certainly part of the answer lies in the special rules, and in particular, in that game’s rule for barbarian ferocity – sort of “Charge/Thrust/Prevail or Bust.” Other parts of the answer are located around who gets an advantage on the various shock evaluation tables, and then there are those barbarian leaders who are likely to be a bit on the poor side compared to a Caesar. And finally, you can just look at the units, and see what the values for this or that look like compared to a veteran cohort. Of course, what you then decide to do with all this information is entirely up to you, but if the game says you have an advantage, however temporary, as a barbarian charging forth and yelling blue blazes, you would be foolish to act contrary to one of the few plusses you are likely to have.

In all, there is no doubt in my mind that where the series really shows at its best is wherever it can get most of its colours out of the box and paint a bigger and more interesting picture. Given the variety of unit types, weaponry, formation, armour, as a general rule, the more of everything you have at the party, the richer the experience will be. But you need to know what you are doing. This is more than just acknowledging that you are looking at a complex set of rules; it is understanding that the interactions between the forces you command and those which oppose you are seriously intricate – just like chess, and then some. And while a lot of knowledge of one game can be transferred to another, you have to be wary of tactical changes when the same nation is viewed at different points in its military life. Having lightly criticized the system for certain things, it is time to acknowledge that working at such a level of detail is often the only way to capture the nuances of military development. If you have both SPQR as well as something presenting battles from the last days of the republic, like Conquest of Gaul, you can compare the nature and practices of the legions across the designs.

Another feature of the series is that depiction of contesting armies from very different cultures and military traditions – something I referred to earlier. This can also bring us backing to the question of planning, for when it comes to some of the most famous engagements featured in the annals, you simply cannot divorce them from their plans, or the plans from the nature of the forces deployed…or from the commanders doing the deploying. One of the clearest examples I can give of this is Cannae. Here were two sizeable armies, though one was, in all probability, markedly bigger than the other. That larger army could be described as a homogenous chunk of the Roman state, whilst the Carthaginian army was yet another of Hannibal’s “mix and match” assemblages. The precise nature of that mixture, of course, applied to considerably more than simply where the troops had come from; in fact, one of the most notable differences in Rome as compared to other powers growing to imperial stature (Persia, to offer another example) was that its forces largely retained the one style of fighting, irrespective of where this or that contingent had come from. By contrast, the army of Carthage had as many fighting styles as it had gods to keep happy.

That bloody day at Cannae the mix outwitted and outfought the mass via a plan honed to the diverse abilities and functions of its units. By contrast, the Romans, if they were going to give battle on the day the dolt was in charge, only really had the one way of doing it…which they did…and got done in with. Perhaps Cannae done in the 1970s would have been a matter of tailoring the range of combat factors and adding some idiocy rules, but look what we have a few decades later – orders of battle that cater not only for the substantial presence of the contesting armies, but also, in painstaking detail, evaluate the capacities of every fighting unit and commander, and relate and modify those particular characteristics in relation to whatever type of enemy unit they are presently engaged with. It is all mightily impressive stuff, but one aspect of wargame design which I do want to introduce here “for later,” is that this is not the only way of producing a valid model of ancient battle. In recent articles I have often talked about wargaming as art, and if I pursue that line just for a moment more, I might ask readers if they are appreciators of creative work that leans towards “all the detail” or prefer “all the feeling.” And beyond that, there is nothing wrong with liking both all the time, and some, some of the time, or finding it just depending on the mood you are in. But it is worth stressing again that GBoH is one take on events, and not the only way of getting a valid result.

But what exactly is “a valid result?” Putting it crudely, you might say it is a result that fits applicable parameters, did not result from playing the system for all it was worth, wringing out every spurious advantage and finding every loophole, and was not assisted by dice rolls that totally broke apart the laws of probability. But still we find ourselves back at the planning and conduct issue. In the GBoH Cannae, there is a lengthy introduction pertaining to the quandaries surrounding this battle when it comes to the historian’s and game designer’s take on things – we may, in the age of Hannibal, be in times better recorded than many before, but there are still gaps; and in the case of Cannae, very considerable gaps and ambiguities, pertaining to the true size of the armies, the true size of the field, and the actual deployment of forces. The designers acknowledge this, but for a battle like Cannae that is only one side of the coin, for having committed the players to deploy their forces in the best interpretation of the record, which in turn infers a depiction of the famous/infamous plans of both sides, how do you then let the game history play out? What is considered within the parameters, and what is not? At varying levels this affects, and has affected, games right across the hobby. No Roman player worth his salt is going to walk as obligingly into the Carthaginian trap because he has read all the histories and can see all the field. For some games this is a big issue, for others the mechanisms and a few extra rules do provide solutions. The Civil War Brigade and Napoleonic Brigade Series (The Gamers) offer a game version of initial historical orders just to start things off. In GBoH the saving grace might well be found in the command rules, which will still leave players with their copious servings of omniscience, but often have the “doing something about it” lagging some way behind the unfolding of fate.

GBoH – The Leaders

Leaders in this series can potentially do all sorts of things superbly, averagely, or abysmally. However, the most important thing they do, or utterly fail at, is keeping their armies on the move and in the fight, and thus one or two steps ahead of their opponent. Elite leaders are adept at this – they can be on the enemy before the prayers and the portent taking have been concluded in the enemy ranks, and they can be jumping into that same enemy’s first glimmer of initiative and slamming the brakes on.

This is important in the matter of the treatment of plans in a number of scenarios – the real Alexander at Gaugamela, and likewise the game one, must move first and move quickly; and thanks to his ratings and the game’s mechanisms, even Darius’ more promising moments are going to look like hasty reactions to the strike of the phalanx and the Companions. In other words, the plans that belong with the respective deployments are going to have a fair chance to evolve realistically, or get realistically curtailed early on.

But how much of that is really due to what brilliance the commander is showing on the field? To put it bluntly, I am not sure how much “commanding” Alexander did once battle was well and truly underway. Numerous military commentators have highlighted Alexander’s ability to read a field and find the weakness in his foe’s deployment. That was undoubtedly one of his major strengths; but, by contrast, once battle was underway, his ability to affect events beyond his immediate location was doubtful – he was too busy fighting and adding to his collection of wounds. And even if he were still some little distance from any immediate broil, the ability, let alone the desire, to influence events elsewhere must have been limited. To an extent, I prefer to see the abilities of the better commanders in these games as also reflecting the better troops they had around them. Alexander’s Macedonians and their allies knew what they were doing because they had been trained that way, and could largely be relied upon to act appropriately for the situation at hand. This, as much as overt leadership qualities, is what enabled them to pack the game moment with more activity than their enemies. Nevertheless, in one of this world’s persisting ironies, entering combat, like engaging in marriage, is one of those activities one should really thinking about as you are likely to be committed to something you cannot readily get out of. Throughout history, battles have had a tendency to be won not so much by the forces that engaged first, but by who had something left to throw in later. If you have a crushing numerical and/or qualitative superiority, you might have plenty of opportunity to move on by dint of killing or driving off anyone you were stuck to; otherwise, unless you have something else to throw in somewhere else, you really are likely to be stuck in a broil where any leader is going to be struggling to find a solution.

One only has to think of many a GBoH field, with a messy battle well advanced, and with flipped units and status markers all over the place, to understand the need to keep something back for the crucial moment. And it is all the better if you have a capable leader to hand to move those units to where they need to be. But leaders, within the broad definition of the “heroic age,” often felt under some form of compulsion to act heroically. Thus, for the leader for whom leading simply means “being in the lead,” GBoH also offers the facility of personal combat. In its own way it is revealing that the series offers an involved little subsystem for such occasions – simply banging dice together is not quite enough. What you get out of this provision by way of entertainment might just depend on what you carry into it; for me, although serious matters are clearly at issue, I always get a wry smile out of one of the rules for this little venture into the predilections of the human ego. Normally, if more one than leader from the same side could champion the cause against the fellow on the other side of hurly-burly, he who possesses the higher charisma rating is the one who shall step forth; and if they share the same charisma rating (i.e. they both have a mighty high opinion of themselves), it is left to the player’s option as to who will accept the challenge. I, however, cannot wholeheartedly agree with this – I think the two allied leaders should have a bit of a brawl between themselves first, and thus decide. After all, what if history’s Alexander had merely been one half of identical twins? It hardly bears thinking about…or does it?

I have already stated the rather obvious – GBoH is a complex game, comprising involved rules and various tiers of decision-making whilst you are playing. It probably is not for everyone; nothing in the hobby ever is. But beyond the issues of lengthy rules, there are the issues of marker clutter and repetitive mechanical functions. To be fair, not everyone in the hobby by any means is put off by markers cropping up everywhere, or having to handle administrative tasks that are not directly to do with the drama you are meant to be experiencing. Status markers are pretty much integral to the system when all the knobs are turned on; and flipping units to show moved and not moved is also something you are going to have to face up to if you are going to play the series with everything it has to offer. And then, it is really up to the player to decide if the system’s myriad of small parts presents the right sort of big picture.

Thus far, through both parts of this study, I have largely been aiming to record the struggle for authenticity within ancients designs, and it would be churlish now to abruptly switch the evaluation process and so turn on a series I have previously been praising. However, it is beyond dispute that a certain form of detail, a particular level of authenticity, does come at a price; and that price is that we sacrifice “game” for “simulation.” At either extreme designs can struggle for an appreciable wargaming audience – a total absence of detail is not going to appeal to anyone, and too much without compensation will deter interest in its own way. The potential audience for any design idea is going to wax or wane at least partly through where it comes to rest on the gauge between game and simulation, and as we finally take our leave of GBoH, we do indeed find ourselves looking at something sitting somewhere else on that measure…

Commands and Colors: Ancients – All Hands and Decks

So what exactly is C&C:A? I ask this question because many of us will be aware of its ancestry, and that much of that ancestry consists of games with soldiers rather than precise military modeling. But so what? Many wargamers enjoy the likes of Battle Cry and Memoir 44 for what they are without getting bothered about what they are not. But C&C:A is a different beast – it may have mechanisms similar to the earlier games in its line, but then, such mechanisms are very much suited to at least some of the structures of command and combat on the antique field. And in battles that are far more about people and the qualities of the fighting man than they are concerned with chunks of metal rumbling around on tracks, the presentation of strength and the consequence of combat can be that broader brushed and still get things far more right than wrong.

So what exactly is C&C:A? I ask this question because many of us will be aware of its ancestry, and that much of that ancestry consists of games with soldiers rather than precise military modeling. But so what? Many wargamers enjoy the likes of Battle Cry and Memoir 44 for what they are without getting bothered about what they are not. But C&C:A is a different beast – it may have mechanisms similar to the earlier games in its line, but then, such mechanisms are very much suited to at least some of the structures of command and combat on the antique field. And in battles that are far more about people and the qualities of the fighting man than they are concerned with chunks of metal rumbling around on tracks, the presentation of strength and the consequence of combat can be that broader brushed and still get things far more right than wrong.

At the heart of the C&C:A system is a take on the rock/paper/scissors expression of fighting capability – some troop/weapon types are better against some opponents than others, and either inflict more damage or suffer less. Albeit achieved by different means, this is much the same as with GBoH. Over the course of this series, it has seen battles presented from the Classical age through to the latter days of Imperial Rome. I would be hard put to say that there have been any particularly “bad fits” because the system is far more mutable than GBoH – the scale seems to adjust with the battle concerned, so you can have even the smaller fights of history presented with plenty of stuff on the board. As for bland shoving matches, you always have the frisson of the passage of cards through your hand, and if one battle proves to be a disappointment, it is no great effort to set up something else. But in some ways, the cards are the system’s biggest potential weakness, and I will come to that presently.

Two other things that need to be mentioned here are that, in its epic form, there is nothing in the hobby to match what is going to be set out in front of you. With the iconographic depiction of so many soldier types, and lines extending across a considerable length of board, this is a dream to get involved with if setting the scene is really part of your experience. Furthermore, you are not going to get so much as a single marker put on top of anything. It is all just visual glory from beginning to end…

But

When things are this good it might be considered nit-picking to fault the game for its obvious omissions: such as absence of specific unit morale and having consistent fighting strengths even in the face of casualties to any given unit. However, there are other areas of weakness which I feel are somewhat more pronounced:

- There is only one set of cards each for either standard or epic C&C:A, offering exactly the same permutations to both sides – in other words, whilst the contingents differ from host to host, everyone is essentially waiting for the same sort of things.

- You cannot plan – or at least not easily.

Let me quote here from Richard Gabriel’s book: The Great Armies of Antiquity

“Philip’s reforms had created the Macedonian phalanx, which, if anything, was even heavier and less capable of complex maneuver than the old phalanx. Alexander’s tactical contribution was to use his heavy infantry in an entirely new manner while reducing its role as the primary killing arm. Alexander used his heavy infantry to anchor the center of the line and to act as a platform for the maneuver of his primary striking arm, the heavy cavalry armed with the javelin. He coupled this new tactical idea with another, the oblique formation. The infantry was not deployed as the foremost frontal point of the line but held back obliquely in the center while the heavy cavalry deployed in strength on the right, connected to the infantry by a hinge of elite cavalry. The idea was to engage the enemy on the flank and force him to turn toward the attack.”

Now how easy is it to coordinate anything like this on the C&C:A battlefield?

From a certain and quite reasonable perspective, referring to such a text in relation to C&C:A could seem a bit over the top. It is a great game, and for many that will enough. But from another perspective, one that wishes to treat with realities on the ancient field, and sees this design as so very close to attainment, I would have to disagree. For me, C&C:A could ideally be seen as a different way, a lighter and more impressionistic way, of presenting and processing the fundamental passages of battle; and if I want that to be the case, whilst doing Issus or Cannae or Gaugamela or Marathon the C&C:A way might well involve different tasks to doing these same battles via GBoH, I should end up with much the same things happening. The problem I have with C&C:A is that the tempi are artificially lost whilst waiting for the right cards, and the natural postures and movement of forces can be distorted simply because you have been  hamstrung by the cards in your hand. And the important thing is that nothing in the Gabriel quote regarding the practice of the Macedonians is beyond the capacity of C&C:A if only it had some tailored decks and some different ways of putting those cards into the player’s hand. In this context I sincerely hope the new C&C:N expansion proves a success, as it may pave the way for the same thing for its sibling.

hamstrung by the cards in your hand. And the important thing is that nothing in the Gabriel quote regarding the practice of the Macedonians is beyond the capacity of C&C:A if only it had some tailored decks and some different ways of putting those cards into the player’s hand. In this context I sincerely hope the new C&C:N expansion proves a success, as it may pave the way for the same thing for its sibling.

In the meantime, do we have any form of mitigation? The one thing I can offer in that regard is that the better armies with the better leaders do get larger hands, but that is not much of a solution IF you think there is any validity in my argument. One alternative could take the form of smaller “national” decks with some specific actions neatly tailored to the hosts in question, and which would augment the base deck rather than replacing it. This would give players better access to the tactics and evolutions of the soldiers making up the army under command.

Of course, Richard Borg has proved a very capable designer who could rightfully point to the stunning success of his ancients series, but the very  fact that C&C:N is in the process of being enhanced by the Generals, Marshals & Tacticians expansion rather suggests that there is room for a like improvement with C&C:A. Without doubt, some aspects of how different armies fought can be captured in the layout of the unit capability tables as well as the odd rule in the booklets. But that is not the same as adding a few cards to season an army’s tactics, or highlighting the military genius of the greats. At the moment, a rule for this and a rule for that, coupled with the functions charts, is a bit like seeing the ingredients but not ever really seeing the cake.

fact that C&C:N is in the process of being enhanced by the Generals, Marshals & Tacticians expansion rather suggests that there is room for a like improvement with C&C:A. Without doubt, some aspects of how different armies fought can be captured in the layout of the unit capability tables as well as the odd rule in the booklets. But that is not the same as adding a few cards to season an army’s tactics, or highlighting the military genius of the greats. At the moment, a rule for this and a rule for that, coupled with the functions charts, is a bit like seeing the ingredients but not ever really seeing the cake.

For me, the biggest issue is simply moving forces in line with how they got set up in the first place. I somewhat shied away from criticizing GBoH in this regard, because the superior leader could always hope to impose his will (and something like his plan) through the mechanisms of the game in conjunction with the ratings he is defined by. But in C&C:A nothing moves without the cards say-so, and even if you have the better leader with the better army, that is no guarantee that you are going to be able to move what it is obvious to move, or that any move can be reasonably coordinated. At this point the system does at least partially threaten to fall back into a hole marked “game”; but that hardly seems warranted given the best things about the design. I plain do not want to think like that.

But let us face the issue full-on: for a battle like Gaugamela you are given Alexander’s deployment, which in turn was integral to Alexander’s plan…which you have not got the facilities for. Alexander, as we know, intended to move quickly and decide the battle before his extended left flank was overwhelmed. He planned to dupe the Persian left into overcommitting away from his chosen point of attack, and then, with his elite cavalry and the forward tip of the echeloned phalanx, strike directly at Darius. And that is why he deployed the way he did…and why it would be nice to get the plan moving on the game board without going through hands of cards trying to get the right combination just to begin shifting things properly. As it is, Alexander might well still prevail, but for all the good of his deployment, he might as well have spent the previous night complaining about his parents and Hephaistion being in a funny mood .

One solution beyond new cards is actually very simple – so I hope I have got it right! Where there is a notable superiority of command or army quality at game start, you could simply allow that player to pick most of their starting hand as deliberate selections. And you might even permit the player to retain those cards for the next impulse, or freely select some others. Thereafter, the normal rules would apply. In saying this, I am fully aware that, again, there may be plenty of gamers who would want to leave well alone, and I would concur with that sentiment in several other aspects of the overall design. This, I believe, is a fantastic system which has its own take on things, so while I occasionally get bothered by the want of strict facing and the fact that killing off a unit of elite Thessalonian cavalry counts just the same in the victory stakes as slaying Borat’s distant ancestors, this is a game that would be killed by procedural clutter. And that is why my observations regarding potential improvements have been limited to the cards.

End of Part II

In Part III I will be looking at Lost Battles and Rome At War, and providing a summing up as to where Ancients systems are today, as well as what might be provided in the future.

Fantastic as always. Thanks and kudos!

Many thanks. Part III will follow in a few weeks.

Is there a part three?

I do hope to eventually complete the piece with the third part. Sadly, the person closest to me is very severely ill, and opportunies for writing in the sort of depth the subject requires have been few and far between. Please accept my apologies.

I hope the best for you and yours. Good luck.

Very good read. Did part three get written in the end? Would be very keen to read what the author makes of Lost Battles.

Sorry – just read the other comments, and saw the author’s response above. Wishing him and his family all the best in a difficult time.