By Paul Comben:

Looking for Buried Wargaming Treasure in the BGG Basement

Part 1

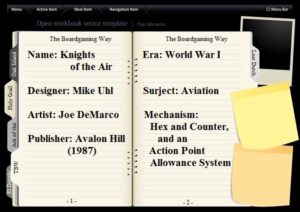

Knights of the Air

By and large we all have an idea how this works – wargames rated over a 9 on BGG are utterly brilliant (and terribly rare); over eight are very good to superb; over a 7 are at least rather acceptable, rising to good the higher you ascend; the 6-point-whatever ratings are likely to be a bit iffy, perhaps very iffy at the low end, but not bereft of their good points if that bit nearer 7; but below 6, oh dear, we hardly ever go there, for down at that level we are among the very old and the utterly outdated, the hopelessly flawed and the completely inadequate. Or so it is thought.

By and large we all have an idea how this works – wargames rated over a 9 on BGG are utterly brilliant (and terribly rare); over eight are very good to superb; over a 7 are at least rather acceptable, rising to good the higher you ascend; the 6-point-whatever ratings are likely to be a bit iffy, perhaps very iffy at the low end, but not bereft of their good points if that bit nearer 7; but below 6, oh dear, we hardly ever go there, for down at that level we are among the very old and the utterly outdated, the hopelessly flawed and the completely inadequate. Or so it is thought.

So what is this article about? Well, it is about wargames that are all rated in the 5-point-something or other on the Geek, but which just might have something about them that tells a different story – and perhaps, just perhaps on occasion, a very different story. What I will not be doing is going back so far in the hobby’s history that we a clearly dealing with the hopelessly outmoded, or being so naively optimistic that I am trying to find some genuine quality in a game that is simply a flawed mess. In short, I have picked out five games all with a rating of 5 point this or that, and taken a look at what these games are really about – is their somewhat dire rating truly deserved; is it too low; too high (!); and has something important been overlooked or simply undervalued? This will certainly not be a series that looks to poke fun at any designer’s efforts, but will consider what might have gone wrong, and as and when quality is found, I will do my level best to bring it to the reader’s attention.

So what is this article about? Well, it is about wargames that are all rated in the 5-point-something or other on the Geek, but which just might have something about them that tells a different story – and perhaps, just perhaps on occasion, a very different story. What I will not be doing is going back so far in the hobby’s history that we a clearly dealing with the hopelessly outmoded, or being so naively optimistic that I am trying to find some genuine quality in a game that is simply a flawed mess. In short, I have picked out five games all with a rating of 5 point this or that, and taken a look at what these games are really about – is their somewhat dire rating truly deserved; is it too low; too high (!); and has something important been overlooked or simply undervalued? This will certainly not be a series that looks to poke fun at any designer’s efforts, but will consider what might have gone wrong, and as and when quality is found, I will do my level best to bring it to the reader’s attention.

And in this, part one of the series, I will get the ball rolling by looking at a 1987 game, designed by Mick Uhl and published by Avalon Hill, Knights of the Air. On BGG this is rated at a whopping 5.7, which ranks it a lot lower than any number of other games I have played and considered a definite disappointment. The subject matter of KotA is aerial combat in the latter part of the First World War – roughly speaking, from the end of the summer of 1917 onward. Unlike the far more recent Bloody April, KotA is very much about plane-on-plane combat, one plane per counter, and is, therefore, in most respects, a dog-fighting game, although specific mission types are varied. In this context, the design follows in the tradition of titles going back to at least the mid-1960s with Fight in the Skies, though I suspect that not a few of us got a first experience of fighting over the trenches via 1972’s  Richthofen’s War. For me, one interesting aspect pertaining to the design history of games on this subject is how varied the level of scientific/technological detail has been – and it certainly has not been a straightforward story of “more modern means more detailed or more complex.” When Yaquinto published Wings in the earlier part of the 1980s, it was almost certainly the most intricate, involved and thorough First World War air combat game the hobby had thus far seen – far more detailed than RW, even with its later additions. In its own way, KotA also aims for a faithful recreation founded on considerably more than simply firing machine guns from a flying canvas and strut platform, but since its appearance (and admittedly, there has not been a vast amount of stuff produced in the intervening years), the tendency has been rather more on keeping things relatively simple and with a strong emphasis on both fun and multiplayer aspects – such as with the more recent version of Blue Max and the colourful mass brawl that is provided by the Wings of Glory system at its best. Then again, Canvas Falcons, from the little I have seen of it, appears to include more detail and complexity than anything before, although its appeal, and also its reach, should probably be regarded as being somewhat on the limited side.

Richthofen’s War. For me, one interesting aspect pertaining to the design history of games on this subject is how varied the level of scientific/technological detail has been – and it certainly has not been a straightforward story of “more modern means more detailed or more complex.” When Yaquinto published Wings in the earlier part of the 1980s, it was almost certainly the most intricate, involved and thorough First World War air combat game the hobby had thus far seen – far more detailed than RW, even with its later additions. In its own way, KotA also aims for a faithful recreation founded on considerably more than simply firing machine guns from a flying canvas and strut platform, but since its appearance (and admittedly, there has not been a vast amount of stuff produced in the intervening years), the tendency has been rather more on keeping things relatively simple and with a strong emphasis on both fun and multiplayer aspects – such as with the more recent version of Blue Max and the colourful mass brawl that is provided by the Wings of Glory system at its best. Then again, Canvas Falcons, from the little I have seen of it, appears to include more detail and complexity than anything before, although its appeal, and also its reach, should probably be regarded as being somewhat on the limited side.

I somehow doubt that KotA was envisaged purely as an “appeal to the hardcore” back in 1987, but any intimation of that probably helps explain a little of why it ended up listed alongside the dire and the disappointing once BGG came into being. But wargames, like any kind of game, can fail for any one of a number of reasons, and in order to get a feel for this particular product, we need to go through the product components, as well as its system. For me, there is no doubt that some games just get off to a bad start by somehow looking off-putting – if not downright ugly. This can be very subjective, but one game that almost made it into my five examples of the “5s” was TSR/SPI’s Barbarossa. Aesthetically, before you ever got to the actual system, the game looked “unhealthy” and distinctly uninviting. Colour, and the use of colour, is important in anything that needs, at least at some level, to look appealing; and Barbarossa got off to a bad start in my book by looking dull to the point of being depressing.

I somehow doubt that KotA was envisaged purely as an “appeal to the hardcore” back in 1987, but any intimation of that probably helps explain a little of why it ended up listed alongside the dire and the disappointing once BGG came into being. But wargames, like any kind of game, can fail for any one of a number of reasons, and in order to get a feel for this particular product, we need to go through the product components, as well as its system. For me, there is no doubt that some games just get off to a bad start by somehow looking off-putting – if not downright ugly. This can be very subjective, but one game that almost made it into my five examples of the “5s” was TSR/SPI’s Barbarossa. Aesthetically, before you ever got to the actual system, the game looked “unhealthy” and distinctly uninviting. Colour, and the use of colour, is important in anything that needs, at least at some level, to look appealing; and Barbarossa got off to a bad start in my book by looking dull to the point of being depressing.

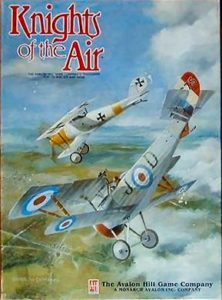

But, by contrast, KotA has a very acceptable piece of box art (an air combat painting by Joe deMarco), along with a mapboard that looks nothing less than stunning. It is a painted, top-down depiction (watercolour as far as I can tell) of a piece of late war Western Front territory, with areas of woods and fields running into a brown wasteland of shelled devastation – all given the perspective of being viewed from several thousand feet up in the air. Of course, KotA is hardly the only air combat game to use a board like this (it is the same “death of the Red Baron territory as RW), but neither RW or any other has ever looked quite this good. To offer another form of comparison, although the components to the latest Blue Max are really rather good (apart from a desperate lack of different aircraft types), the board does not have “the big sky” feel of KotA, which keeps its aircraft counters clear but small, and does not intimate any sense of running off the board edge as you start to wheel around.

But, by contrast, KotA has a very acceptable piece of box art (an air combat painting by Joe deMarco), along with a mapboard that looks nothing less than stunning. It is a painted, top-down depiction (watercolour as far as I can tell) of a piece of late war Western Front territory, with areas of woods and fields running into a brown wasteland of shelled devastation – all given the perspective of being viewed from several thousand feet up in the air. Of course, KotA is hardly the only air combat game to use a board like this (it is the same “death of the Red Baron territory as RW), but neither RW or any other has ever looked quite this good. To offer another form of comparison, although the components to the latest Blue Max are really rather good (apart from a desperate lack of different aircraft types), the board does not have “the big sky” feel of KotA, which keeps its aircraft counters clear but small, and does not intimate any sense of running off the board edge as you start to wheel around.

To be blunt, if you are looking for a big collapse in KotA’s ratings for any component deficiency, you will, for the most part, be searching in vain. More aircraft types would have been nice, supplying a broader look at the air war, but I do not think that played more than a very negligible part, and probably none at all, in terms of how the game has been rated. When looking at one other key component of the game, I feel we get our first serious intimation of what the designer was seeking to achieve. The part in question is the set of aircraft performance cards, which are substantially larger than those for the aircraft types in the Yaquinto game, but within the design model of KotA, work to much the same purpose – profiling the plane in question regarding its armament, engine performance, climb and dive rates, and the range of maneuvers the aircraft is capable of. In places, especially in the maneuver sections, things do get a bit small given how much detail is going into each panel, but nearer the bottom, the cards really do introduce the essence of the game. As far as possible in a board game, you are going to fly these planes – the tracks and the accompanying markers for the control stick, throttle, climb/dive attitude etc. are meant to convey some sense of being in the cockpit; a hard thing to do with paper and cardboard, and I wonder if the designer at least toyed around with a form of background presentation for these cards that would have fitted these tracks into some kind of actual cockpit representation?

Having the tracks mimicking an ammunition belt or drum, a throttle track next to where the throttle for this or that plane would have been in real life, the control stick in front of you and just enough graphical accompaniment to further the mood would have been a remarkable thing; but as it is, the tracks are simply in the sort of order you would expect from a set of cards of this type, and maybe that was an opportunity missed, although it must be said that the cards do have to hold a great many different pieces of information.

Nevertheless, one reason my thoughts turn this way is my recollection of another Mick Uhl design from about ten years earlier. In what has always been known as Gettysburg 77 (well, at least since 1978), Mick showed a real desire for doing something utterly different with a battle that was already a multi-title subject. The three versions of Gettysburg that went into the game box have been described in a variety of ways over the years – the basic version is generally, and rightly, seen as an unfortunate waste of time – with, amongst other things, a jarring mismatch of components; the intermediate model is the one players appear to prefer; but I tend to think that the designer’s vision was all about the advanced version, with its detailed battery compositions, its command rules, and its brigade frontages. I could well have included that game in my series, but it is far too long since I owned and played it. However, I do recall the radical difference in look and feel that the advanced version had, and I believe I recall the designer taking pains in an interview included in The General to highlight what he was hoping to achieve. In this context, the fact that most things in the overall package fell short is neither here nor there; what matters is the passion of a designer to do something different, and I think this was still very much his ethos when it came to KotA.

Nevertheless, one reason my thoughts turn this way is my recollection of another Mick Uhl design from about ten years earlier. In what has always been known as Gettysburg 77 (well, at least since 1978), Mick showed a real desire for doing something utterly different with a battle that was already a multi-title subject. The three versions of Gettysburg that went into the game box have been described in a variety of ways over the years – the basic version is generally, and rightly, seen as an unfortunate waste of time – with, amongst other things, a jarring mismatch of components; the intermediate model is the one players appear to prefer; but I tend to think that the designer’s vision was all about the advanced version, with its detailed battery compositions, its command rules, and its brigade frontages. I could well have included that game in my series, but it is far too long since I owned and played it. However, I do recall the radical difference in look and feel that the advanced version had, and I believe I recall the designer taking pains in an interview included in The General to highlight what he was hoping to achieve. In this context, the fact that most things in the overall package fell short is neither here nor there; what matters is the passion of a designer to do something different, and I think this was still very much his ethos when it came to KotA.

So, if we are looking for that vision, what can the game’s rules tell us? One interesting aspect of the KotA rules is that they seem relatively short when compared to those for Wings. If you have never seen that particular booklet, it is a substantial document for a game that offers far more planes and a chance to get as serious about the “pushers” and Eindeckers as with anything else contesting the skies, or strafing and bombing, in 1918. Certainly, one reason why the Yaquinto booklet is so much more substantial is because of the design’s greater scope. But once you strip out the matter pertaining to dropping bombs and taking photographs of this or that enemy position, and once you have also subtracted those sections of rules pertaining to Zeppelins, observation balloons, anti-aircraft fire and the bigger or smaller peculiarities of obscure aircraft types, you are left with the essence of getting one or other of these games up and running – i.e. how they handle the science of flight and the process of combat.

So, if we are looking for that vision, what can the game’s rules tell us? One interesting aspect of the KotA rules is that they seem relatively short when compared to those for Wings. If you have never seen that particular booklet, it is a substantial document for a game that offers far more planes and a chance to get as serious about the “pushers” and Eindeckers as with anything else contesting the skies, or strafing and bombing, in 1918. Certainly, one reason why the Yaquinto booklet is so much more substantial is because of the design’s greater scope. But once you strip out the matter pertaining to dropping bombs and taking photographs of this or that enemy position, and once you have also subtracted those sections of rules pertaining to Zeppelins, observation balloons, anti-aircraft fire and the bigger or smaller peculiarities of obscure aircraft types, you are left with the essence of getting one or other of these games up and running – i.e. how they handle the science of flight and the process of combat.

Such aspects in KotA, as with any other game on the subject, can be broadly divided into issues of how the design handles details and events in and around the cockpit, and allied to that, how the model carries an aircraft around the sky. Complexity in this regard is not really about, or at least not purely about, having a bundle of different rules to remember and work with – it is far more a matter of how the concepts presented sit with the reader, and how their ensuing implementation challenges the intellect. Of course, this might be said of any game – recalling the very first edition of Third Reich, the actual mechanisms of production, movement and combat were not that difficult each in themselves, but the challenge of doing the right thing in every unfolding context was considerable.

Such aspects in KotA, as with any other game on the subject, can be broadly divided into issues of how the design handles details and events in and around the cockpit, and allied to that, how the model carries an aircraft around the sky. Complexity in this regard is not really about, or at least not purely about, having a bundle of different rules to remember and work with – it is far more a matter of how the concepts presented sit with the reader, and how their ensuing implementation challenges the intellect. Of course, this might be said of any game – recalling the very first edition of Third Reich, the actual mechanisms of production, movement and combat were not that difficult each in themselves, but the challenge of doing the right thing in every unfolding context was considerable.

And within its own sphere, KotA offers its own challenges about touching anything that might disastrously affect something else. This might be intimated to the gamer simply by a first skim of the rules, which tell of a game where learning what a pilot can do with a plane, and what the plane is prone to do in a range of given circumstances, warns of far more going on than simply pushing an aircraft counter to a given point and then blasting away with the guns.

Let us start with the pilot. In at least some air games, the pilot is really nothing more than a dumb proxy to carry the status of healthy, wounded or dead through the passages of play. Of course, most air games seek to give a quality to whoever is representing the player’s game life – aces and the more experienced can do more things, are often the better shots, and in some designs where this is featured, are less likely to panic. By contrast, the rookies have far fewer tricks up their sleeve, may not shoot nearly so well, and again, where it is featured, may even have trouble finding home and landing their crate.

KotA, to a certain extent, follows much the same sort of pattern – better pilots have better maneuvering ability, and aces shoot better than non aces. But where KotA does something rather differently to at least some other titles is in seeking to bind the proxy pilot and the player together in a more palpable sense. This is done largely through the decision-making process connected to the spotting and pursuit rules. Basically, you can only go after enemy aircraft you can actually “see” – i.e. aircraft you have spotted. Part of this is pure mechanism, in that you roll dice to ascertain a raw spotting range from different aspects of your plane’s orientation. This range is then modified by factors such as pilot experience, the presence of an observer, altitude differentials and where exactly an enemy is in relation to where you are – in other words, an enemy right in front of you is going to be easier to see in most circumstances than one who is lurking around the tail of your single-seater.

Where things get really interesting with this system is when, after ascertaining who is spotted, the player decides whether or not to commit to pursuing a particular enemy that he has brought into view – a selected target is marked with a chit to assign an attacker. At this point, the proxy gives way to the actual player, with the player forced to decide whether chasing after this or that plane is worthy of the effort. The rules are at pains to make it clear that there are both advantages and disadvantages to committing to a target – broadly speaking, you get some advantage in movement sequencing versus your chosen prey, but it comes at the price of losing some reaction to whoever has turned their attention your way.

Most air combat games confer advantages for tailing or at least having some form of advantageous position, but, of the several 1914-18 air combat games I have played over the years, this is the only one where, in the chaos of a dogfight, consideration is given to the simple ability to see an opponent and, most importantly, the decision that you then make about that. Of course, the mechanisms for this have to rub against the simple reality of player omniscience – all the planes are on the board, so, in reality, you can still “see” what, in game terms, you are not meant to have noticed. But as the game also specially precludes you taking action against anything other than what you can see or have “fixed” upon, the system works rather well.

Of course, it takes getting used to – the sequencing of moves in terms of spotting and pursuit is a little complicated, but, for the most part, is pretty instinctive. And what it allows the game to recreate is chains of pursuer and pursued, something vividly presented in a 1963 BBC interview with the British veteran pilot of 1916-18, Cecil Lewis, who spoke of often seeing one plane on the tail of another, and another tailing him, and then the same again. The one question apart from the effect on progressing the game, is how such processes may affect player psychology, and whether, in particular, it offers just a hint of the dogfight mentality, where hanging back might keep you relatively safe, but in most cases, it is only by commitment that you can hope to put a plane in your sights. This is important, for some of the most notable instances of the death of an ace occurred through too zealous a pursuit – it played a part in the death of Mick Mannock, and also, most notably, von Richthofen.

One other thing that is inferred by these game aspects is the value of having a capable observer in one of the more decent two-seater planes of the period. The game naturally “invites” tail attacks against single-seaters, not only because there is no defensive armament in that direction, but also because the scope for detection is much more limited. However, with that extra pair of eyes, and one or two machine guns covering the area, going for the rear of a two-seater is that much more formidable a prospect – unless the observer gets things wrong.

Sadly, this is one part of the design where omniscience has held sway over realism. Then again, it might just be a matter of interpretation. What I am referring to is the sort of instance related by another British Flying Corps veteran: on a photo-reconnaissance mission in a RE8, our pilot spoke of seeing several Albatross scouts away in the distance, and urged his observer to keep an eye on them. Unfortunately, the observer insisted, mistakenly, that they were Nieuport scouts, and then, far from watching out for them getting closer, became engrossed in his camera work…until the Albatross flight put several bullets in him and left the RE8 pilot with no other option than to make a tight circling descent to the ground – which by a miracle he just about managed in one piece. Mistaken identity, however, does not play a part in the spotting aspect of this design – unless it is somehow construed as being built into a particularly bad spotting result. It is not a major issue either way, given that any game can collapse under its own weight if you try and pack too much in, and that, for all the science that shapes the best examples of our specialty, any board wargame is an impression before it is anything else.

Having introduced the pilot, and, to some extent, the observer, we can look at the machine guns they will be employing. Taken purely in isolation, there is nothing that remarkable about the process by which guns inflict damage, and how that damage is represented. Within KotA’s mechanisms, planes have the customary damage points assigned to various parts of the target, as well as a possibility of inflicting numerous types of critical or semi critical hit. But where it all gets a bit more interesting is in the way the design seeks to work fire opportunities within the concept of a fluid, ever-changing dogfight. Most air combat games I have played have tended to place weapon-firing after movement, and/or have had some limited form of opportunity fire. In KotA however, there is a real effort to give some feel of a plane either coming briefly into your sights during a pursuit, or of a plane stunting out of the way of your guns even as you are readying to fire. The ironic thing is, that in order to create this “fluid” approach, the movement of a target and its pursuer is rendered that bit more stop-start. Both defender and attacker are given opportunities in the fluid move to halt proceedings and attempt either fire or evasion. And to give an even greater sense of combat being about fleeting opportunities in ever-fluctuating situations, the game also employs a timing mechanism to ascertain where opposing planes are at the moment the action gets stopped.

KotA is not entirely alone in having a provision for relating relative speed to location at key junctures – in the late 1960s, Avalon Hill’s 1914 had an optional rule to convey the fact that different units with different movement provisions were going to arrive in particular locations at different rates, but such rules are rare, and I assume that is because they are commonly far more trouble than they are worth. In the case of KotA, where either side is unlikely to have more than three “units” to move, the system may seem eminently more manageable, but it will inevitably lead to pauses in the action, and as I said, this despite the rule being all about conveying the pace and the unforgiving nature of each instant.

KotA is not entirely alone in having a provision for relating relative speed to location at key junctures – in the late 1960s, Avalon Hill’s 1914 had an optional rule to convey the fact that different units with different movement provisions were going to arrive in particular locations at different rates, but such rules are rare, and I assume that is because they are commonly far more trouble than they are worth. In the case of KotA, where either side is unlikely to have more than three “units” to move, the system may seem eminently more manageable, but it will inevitably lead to pauses in the action, and as I said, this despite the rule being all about conveying the pace and the unforgiving nature of each instant.

Something that did surprise me about combat in the game was my first sight of content that has been broad brushed. Unlike some games, there is no fraught, problematic reloading of those wing-mounted guns set above the cockpit – such as on the SE5 and SE5a. Again, Cecil Lewis spoke of having to replace the drum of a Lewis Gun in the midst of battle – trying to get the empty drum off, a new drum clipped in place, and all this while trying to control the plane, watch for danger, and essentially try and keep things level with an aerodynamic nightmare pulled right down in front of you. KotA keeps clear of this, and also, without the relevant optional rule, of any direct player decision to employ a shorter or a longer burst. What the game does is relate the amount of bullets sent towards the target to the speed of the aircraft involved, and the aspect of the target to the attacker. Obviously some aspects, and less combined speed, will afford a greater chance for more potential damage to be sent on its way, and will also determine the likelier hit distributions when bullets strike home.

If I turn now to KotA’s mechanisms for flight, then, although there is much that is different from other games, it is still an approach to that fundamental challenge facing all air combat simulations – how to present three dimensional movement on a two dimensional surface. There are probably as many techniques for this as there are games on the subject. Some games keep things as straightforward as possible, with only the most basic representation of altitude change – just enough to give a sense of a plane diving or climbing. Some, such as the most basic form of Wings of Glory, eschew even this, as did the basic form of the air combat book series, Ace of Aces.

If I turn now to KotA’s mechanisms for flight, then, although there is much that is different from other games, it is still an approach to that fundamental challenge facing all air combat simulations – how to present three dimensional movement on a two dimensional surface. There are probably as many techniques for this as there are games on the subject. Some games keep things as straightforward as possible, with only the most basic representation of altitude change – just enough to give a sense of a plane diving or climbing. Some, such as the most basic form of Wings of Glory, eschew even this, as did the basic form of the air combat book series, Ace of Aces.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, KotA has a much more detailed approach, designed to represent engine power and lift at all playable altitude levels, and relating this to the amount of time it takes to perform a specific action. The game allocates a number of activity points to much that the plane or the pilot can opt to do, and it is far from unlikely that actions initiated in one game turn will only be completed in the next. All of this works with the overall concept of the ongoing combat event, and the player needs to understand that part of the mastering of the game is not only learning how and when to perform the maneuvers available to any given plane type, but also developing an understanding of how long an action committed to is going to take.

Admittedly in an abstracted form, the design does give you a control stick and a throttle, and performance is linked not only to how you manipulate the positions each can have, but how your plane responds at different marks of altitude. If you introduce the optional rules for the transition of potential energy into performance, and the fact that different plane models have different degrees of inherent agility, things can get that much more complex, and perhaps beyond the desire of the average player to undertake.

As I have already said, there are some things either not incorporated into the main body of the rules, or plain not present at all. Personally, such absences do not bother me, given where the designer seems to have made a deliberate decision to place his emphasis. Among those items totally absent are cloud cover (to be blunt, any sort of cloud counter would markedly affect the game’s aesthetics as far as I am concerned); and the effect of a prevailing wind direction (a factor that can, and did, “drift” planes over enemy lines, or give them a slower, tougher time getting back to their home airfield.

But I doubt if these matters counted a jot in terms of the game’s rating. So what did push it down so far? One interesting thread on the design’s BGG page suggests that it is largely due to the design being “a wargame.” Well, so is ASL, but there the complexity, whilst causing plenty of gamers to steer clear, does not mean that they want to drag the game’s rating into the abyss. There may be a bit more validity in saying that it is an old wargame, and old wargames do not always fare that well in ratings systems. I do not think the game looks old, or in any way “past it,” but it is nevertheless nearly thirty years old, and that is a serious whack of time by anyone’s reckoning.

For me, the likeliest explanation is that this design came out with a perfectly valid, indeed in places, brilliant concept, but it was not the sort of concept the broader hobby was going to fall in love with. It is a shame, because when I see great design, I will want to applaud and recognize it, even if it is not for me. Having said all that, KotA’s “invitation to play” is still somewhat equivocal – lovely map, decent counters, and a theme that I suspect many of us find attractive enough, but the aircraft data cards warn of trials ahead. In particular, certain of the maneuvers on certain of the cards look like equations and formulae posted in an advanced science lesson – which is just about what they are, and what they are meant to be.

As I intimated earlier, for the broader range of gamers, the air combat of the Great War is probably best enjoyed in attractive systems which can facilitate a whirling mass of planes banging away at each other (like Wings of Glory), or have other provisions that can get the chores and the hard work done for you – Dan Verssen’s enjoyable and far from unrealistic card game, Flying Circus, being an obvious example. I daresay you could fight a big air brawl with KotA, but it would not move very fast, and it would take a serious amount of commitment and care to ensure that the sequencing remained viable.

As I intimated earlier, for the broader range of gamers, the air combat of the Great War is probably best enjoyed in attractive systems which can facilitate a whirling mass of planes banging away at each other (like Wings of Glory), or have other provisions that can get the chores and the hard work done for you – Dan Verssen’s enjoyable and far from unrealistic card game, Flying Circus, being an obvious example. I daresay you could fight a big air brawl with KotA, but it would not move very fast, and it would take a serious amount of commitment and care to ensure that the sequencing remained viable.

But whatever this design does not do so well, it is a very good simulation of air combat on the smaller scale. The rating for this game suggests something badly flawed, which it most certainly is not. Providing it is approached with due appreciation of what it set out to do, it should not disappoint anybody.

My personal rating – about 7.5.

If you have access to BBC iPlayer, you will find the interview with Cecil Lewis by searching “Great War Interviews.” Some of his recollections featured in the series The Great War (1964), whilst others were included in the collection Forgotten Voices of the Great War. But iPlayer contains the full session, which lasts for close to forty minutes. Cecil Lewis was, in every sense, a true English gentleman, and as some readers may be aware, he wrote of his own experiences as a pilot on the Western Front in the book Sagittarius Rising.

In the next part of this series, I will be looking at another design set in the Great War, Rob Beyma’s 1981 work, The Guns of August.

Paul Comben