The Lamps are Going Out: World War 1

By Paul Comben:

Now here is a thought worthy of a moment’s consideration: if you took every Great War design the hobby has ever produced and set them on one side of a balance scale, and then dropped the entirety of the hobby’s World War Two output into the other, very sizable pan, the Great War titles would most likely shoot up in the air and head towards the heavens at something like escape velocity.

Well, we all know why – the output of 1939-45 titles has far outweighed those from the 1914-18 period over all the years of the hobby’s existence, and will most likely always continue to do so. On the other hand, when one looks at simulations of the entire span of those two events, the count becomes far closer. Yes, we can argue about just how many fronts or theatres need to be present for any game to be in “in the mix,” but keeping things pretty inclusive and allowing commonsense to reign, we can include the likes of Third Reich (once!), WiF, Paths of Glory, Storm of Steel, Unconditional Surrender, Der Weltkrieg (in its composite hugeness), Axis Empires, Distant Foreign Fields, Balance of Powers, The Supreme Commander…and…Axis and Allies (maybe just twice!).

Well, we all know why – the output of 1939-45 titles has far outweighed those from the 1914-18 period over all the years of the hobby’s existence, and will most likely always continue to do so. On the other hand, when one looks at simulations of the entire span of those two events, the count becomes far closer. Yes, we can argue about just how many fronts or theatres need to be present for any game to be in “in the mix,” but keeping things pretty inclusive and allowing commonsense to reign, we can include the likes of Third Reich (once!), WiF, Paths of Glory, Storm of Steel, Unconditional Surrender, Der Weltkrieg (in its composite hugeness), Axis Empires, Distant Foreign Fields, Balance of Powers, The Supreme Commander…and…Axis and Allies (maybe just twice!).

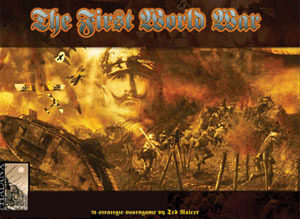

But, in against the welter of different titles, there is one particular niche where the Great War appears to be somewhat ahead in the race – fairly simple and small(ish) recreations of what any reasonable perspective would see as the entire conflict. There is the old (and then revived, revised and renewed) wonder that is Jim Dunnigan’s World War 1; there is another though lesser known fave in the shape of Death in The Trenches; the Ted Raicer-designed The First World War from a few years back (eminently simple and fast-playing); Al Nofi’s The Great War may well qualify but I need to see it close up (and especially its new revised version); but very visible right now as it sits beside me is the fresh and mildly deceptive entry that is The Lamps Are Going Out.

By contrast, the only World War Two game I have ever owned that comes anywhere near the same broad criteria is Hitler’s War – small map, small number of large-scale units, but, on the other hand, the system is pretty detailed (in all fairness, so are some aspects of Death In The Trenches, but that game has a very small map), and it is not really a one-sitting sort of game. Likewise, Blitz seems just too big and involved (albeit possessing an appropriate scale of representation) to qualify for inclusion[1].

By contrast, the only World War Two game I have ever owned that comes anywhere near the same broad criteria is Hitler’s War – small map, small number of large-scale units, but, on the other hand, the system is pretty detailed (in all fairness, so are some aspects of Death In The Trenches, but that game has a very small map), and it is not really a one-sitting sort of game. Likewise, Blitz seems just too big and involved (albeit possessing an appropriate scale of representation) to qualify for inclusion[1].

So what about Lamps? Or, to put in another way, first of all, what about the war that Lamps seeks to represent? To my mind, there are several aspects of that conflict that make it work as a larger scale game/simulation without the fuss and bother that can troop along with many a 1939-45 title:

- The likelihood of long term fixed fronts means you do not have to finesse the military side of things by working at a more intimate scale.

- The long attritional and largely static period of the war was about wearing-out of nations’ capacity to fight (both materially and in political/morale terms) – things that can be represented by simple mechanisms representing declining or newly arriving (e.g. the US) power.

- The war eventually reached its critical phase when the process of “wearing-down” was accompanied by technology/tactics capable of breaking the deadlock and forcing a decision – again, something that can be readily catered for by mechanisms as simple as new events bringing new modifiers.

The first time I played a 1914-18 game that fitted these parameters was some forty years ago, and the game in question was the Jim Dunnigan design. In many respects, what was presented “on map” in that game was secondary to the simple expression of national power expressed in straightforward numerical terms on a separate track. Combat, losses ensuing from combat, and rebuilding or augmenting forces all cost resource points, of which, ultimately, there was only a finite supply for any nation. The “solution” was something you were supplied with as the game progressed to its latter stages – the Entente got their tank unit and their US forces, and the Germans got their Stosstruppen-led armies. Which side prevailed then depended on how fragile either side had become by that point.

Fragility, technology, blockades, revolutions and the crises attending decrepit/senile powers (Franz-Joseph’s mob) have also featured in various degrees and blends within these broad scope designs. Death In The Trenches is a game I own but have not played, but whilst it keeps its map small and its counters relatively few in number, like the similarly driven Counterstrike CSA (which I also own and have played) it is seriously adorned with a variety of extras (for the politics and other colour) which nearly nudge it out of category. The Ted Raicer First World War, despite having a far larger map, is far shorter on rules and colour, but has its accents and nuances where it matters – chits depicting the key technological and political evolutions which give the opportunity to experience crisis and opportunity in a system that is meant for quick set up and play

Lamps has something of that “play, change sides, and play again” feel to it; an aspect of the design I must admit somewhat disconcerted me the first time I read the rules as I had made a rather superficial assumption of it being a bigger game than it actually is. This, mark, is not a criticism, merely an observation. Over the last couple of years, we have been treated to a number of new (or newly revised) “whole of World War One” titles, and seeing as how Compass Games produced two of the largest offerings (Balance of Powers and Fatal Alliances), perhaps I assumed/expected their third title on the same theme to be that bit more substantial in its own way. But that was my error, for the game’s designer appears to have been very clear about just what sort of game he wanted, and kept very much to that.

Lamps has something of that “play, change sides, and play again” feel to it; an aspect of the design I must admit somewhat disconcerted me the first time I read the rules as I had made a rather superficial assumption of it being a bigger game than it actually is. This, mark, is not a criticism, merely an observation. Over the last couple of years, we have been treated to a number of new (or newly revised) “whole of World War One” titles, and seeing as how Compass Games produced two of the largest offerings (Balance of Powers and Fatal Alliances), perhaps I assumed/expected their third title on the same theme to be that bit more substantial in its own way. But that was my error, for the game’s designer appears to have been very clear about just what sort of game he wanted, and kept very much to that.

What this happens to be is a game that seeks to cover as much Great War territory as possible, and this via a vehicle with a strong basic framework, and an assortment of card decks driving the design forward. All this comes with a standard sized map, some rather attractive components all round, a set of rules that look longer and more complex than they actually are, and a playing time that is far closer to the mid-Seventies Jim Dunnigan design than to something like Paths of Glory, to which Lamps has a superficial resemblance.

All this is important to someone like myself owing to the want of the hours and the space to set up and play anything bigger. I would love to experience Balance of Powers, but I really do not have the room to set it up and keep it so over a period of days or weeks. So, perhaps not unlike many of us, I want games of modest complexity and footprint that do as faithful and as detailed a job as possible whilst keeping the overall playing time down to manageable proportions. I recognize that this will often mean compromises in terms of detail, but I still want designs that have the right feel, the right ingredients, a sense of immersion in the subject matter, and which give me that valid play experience in a reasonable span of time.

So, does Lamps match up as a valid experience for a gamer who believes he knows the subject pretty well? Let us start with some of the fundamental mechanisms of the game:

So, does Lamps match up as a valid experience for a gamer who believes he knows the subject pretty well? Let us start with some of the fundamental mechanisms of the game:

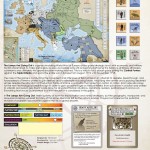

The map is separated into large areas (the entire Western Front will only span an opposing pair of these, and the Eastern Front an opposing three or four at the most), and also features African, naval and procedural types of inset. The greater part of the unit counters represent armies. Cards, divided into event and technology decks for the composite alliances, and refined further by historical chronology, are provided for the various factions within the contending alliances – essentially the major powers according to their main front and then the smaller and/or later arriving nations. However, in a perfectly logical step, technological advances are contained in decks that represent the reality that all the hideous driving force of better killing is going to come from the major protagonists.

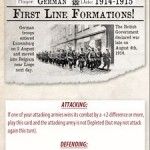

When you look at the cards, they are, depending on your overall knowledge of the period, quite predictable in their subject matter, but, in some instances at least, perhaps a little open to question in their precise effect. But this is where I found myself toppling somewhat between two stalls – i.e. between acknowledging that this is meant to be a straightforward quick-playing game, and my own desire for just a little more finesse and detail in places. To give an example from the early going, the Entente and the Central Powers possess “First Line Formations” cards that confer a +2 DRM to any combat to which the card applies[2]. What, you may ask, is wrong with that? Well, in a sense, absolutely nothing…unless you want a little more than all armies from all factions more or less acting the same. Something that I would have preferred, and might try out, is varying the “First Line” effect depending on precisely who is fighting who: e.g. in the case of Russian armies in combat, there is nothing wrong with a +2 modifier for attacks on the forces of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, but against the Germans maybe the modifier should have come down to +1.

This, I must confess, was a rather ongoing theme for me as I read through the rules and found myself just wanting a touch more finish or colour in places. The event cards can give you a passing sense of a “Verdun,” but I wondered about the pool of trench markers (in such an instance drawn blind) possibly including salient and fortress “specials.” These would add just a bit more character to the fronts, offering both opportunities and weaknesses that a few supporting rules would “encourage” players to deal with.

I did raise this particular issue with the game’s developer, Hermann Luttmann. Interestingly, he admitted that he had had much the same idea for much the same reason – though he saw salient as conferring an attacking advantage (a launch pad for deeper operations), while I saw them as saddling the owning side with a bothersome liability. Hermann confessed that the mechanism, whilst having appeal, did not readily make a comfortable fit within the overall system. That is reasonable comment, as, by then, I was becoming increasingly aware that I may have been asking more of the system than it had been set up to deliver. Then again, tweaking a few of these “peripherals” might have avoided something else that just jars me a little every time I look at the map.

If you have the map in front of you, you will see production areas rated numerically for how much war and war material each can support. The ensuing pool of points elegantly presents the ability of nations to sustain war with new forces or rebuilt forces. The problem is, whilst it certainly works, it gives the appearance of working (if I understand the relevant aspects of the game’s development) as an obvious fix to a subtler problem. The problem was/is play balance (witnessed in playtest versions), and the fix, as I understand it, was to give Germany, within the context of the design, a greater productive output by itself than Britain, France and Russia combined. I cannot help thinking that the game imbalance reported in the test process (with Germany being crushed by 1916), could have been more invisibly mended by honing the content of the cards.

If you have the map in front of you, you will see production areas rated numerically for how much war and war material each can support. The ensuing pool of points elegantly presents the ability of nations to sustain war with new forces or rebuilt forces. The problem is, whilst it certainly works, it gives the appearance of working (if I understand the relevant aspects of the game’s development) as an obvious fix to a subtler problem. The problem was/is play balance (witnessed in playtest versions), and the fix, as I understand it, was to give Germany, within the context of the design, a greater productive output by itself than Britain, France and Russia combined. I cannot help thinking that the game imbalance reported in the test process (with Germany being crushed by 1916), could have been more invisibly mended by honing the content of the cards.

So, I am complaining about broad brushing, yes? Well no, as every creative effort needs more than one brush – or in the case of Jackson Pollock, no brushing at all – so it is more a case of what gets used where. There are certainly cases where broad brushing works very well in this design, and one area I would highlight for that is in the tension on either side of the North Sea pertaining to fleet commitment. On the face of it, the fleet combat mechanism looks simple bordering on simplistic – if there are contending fleet units in the relevant North Sea Blockade Box, you fight a combat that is simply about dice results. Have a bad time in one set of rolls, and that is your fleet on the seabed. But this totally conveys the “lose the war/win the war in an afternoon” trauma affecting both sides. Jutland, in terms of the full fleets coming into action, lasted a mere matter of minutes, and yet, in that very brief span of time, it very nearly lurched into being an utter disaster for the High Seas Fleet. The design does a nice job here, and also rather goads the German player to do something as later (German) event cards will tell out the blockade story if the German Fleet is either sunk or skulking about in harbour[3].

However, one area where the design’s preference for the painting things bigger could seem a little incompatible with what is actually presented, is in the matter of the East African theatre. More recent studies of the First World War, in both book and documentary form, have stressed the “world” nature of the conflict, and that reflecting campaigns with repercussions for the future course of history in Asia and Africa, as well as the subsequent tumults in Europe. Nevertheless, while the designer’s notes offer a clear explanation as to why the theatre is there, there may still be uncertainty among players as to whether the theatre has a place in a game operating at a main scale of armies of hundreds of thousands and bitterly contested fronts extending over hundreds of miles. Yes, one can say that the far more limited forces in East Africa were capable of producing results/consequences that could never be achieved by similar contingents in Europe, but many might remain unconvinced that anything Lettow-Vorbeck could have done in the theatre in addition to what he actually did, was capable of turning any part of the continent into some vastly enlarged version of Napoleon’s “Spanish Ulcer.”

But this is pretty much what threatened to happen, and to some extent, did actually happen. If readers doubt this, I would recommend the book “Tip and Run” by Edward Paice. In the foreword to this, the author makes it clear that events in sub-Saharan Africa cost the British a serious amount of money, involved a commitment of around 150,000 men, and despite the vast distances and other major difficulties, the Germans made extraordinary efforts to supply Lettow-Vorbeck – including by Zeppelin. In other words, events in Africa disjointed and enticed imperial contentions to no small extent, and it is to the great merit of the designer that this aspect of the war found its representation within the game. And just before anyone thinks I was in tune with this all the way…no I was not. I was someone who initially thought the front in East Africa was a waste of time, but did the reading, had a rethink, and do not mind admitting I am merely being wise after the event![4]

However, I still have a few issues with a few other game features, and to view these, we can look at the very best (with, arguably, the occasional hiccup) that the event cards and technology cards, together with their concomitant mechanisms, have to offer.

As I have already said, a good deal of the game is in the cards; and although these cards often give the feeling that you are experiencing but minor variations in the conflict’s grim chronological progression, in particular areas things are a little more subtle than that. Among the examples I can give is with the treatment of German submarine warfare, where some of the story is on the cards, part within the randomness of a clever U Boat Attrition Table, and some in player (Central Powers) choices. This never really becomes any sort of “game within a game,” but it does add a nice sense of depth – pardon the pun!

Cards supply the U Boats with better patrol/combat effectiveness as well as augmenting their efforts via surface raiders; within the context of the British side of the Entente, cards also supply the various responses to the lurking submarine menace – Convoys and Q Technology – the latter being the “shiftier” side of the British response, which historically included dazzle ships and supposedly helpless cargo vessels that were actually armed to the teeth. The various potential sources of wear on fragile submersibles is reflected in the Attrition Table, while the ability of the U Boats to hurt Entente production and commerce is linked to their tech level and what status such a campaign is in – observing the Hague Convention or Unrestricted. Thus, there is plenty of game colour at work here, which builds tension and supplies a quality narrative within the main themes of the unfolding game.

The one area of the commerce/submarine struggle where I am somewhat dubious is the apparent ability of the German/Central Powers player to “hop” between the different submarine warfare status boxes whenever he or she wishes. On the one hand, never being certain how “The Hun” is going to tell his U Boat captains to behave from one turn to the next may create genuine game tension, but it does not seem entirely realistic. That is not to say it is entirely wrong. You only have to read the designer’s excellent notes section on the interrelation of factors that led (or in the game, can lead) to US intervention, to see that a very serious level of consideration has been given to this aspect of the design, and that the designer has fully understood the factors in play and has sought to cater for them appropriately. The Germans did embark on unrestricted submarine warfare more than once, and, to put it crudely, could be considered to have “got away with it” for a while. Nevertheless, declaring unrestricted submarine warfare was very much a crossing of the Rubicon, carrying all kinds of political, diplomatic and military consequences beyond the span of the event, and as such “bouncing” alternately and perhaps repeatedly, between the status boxes seems a little too loose for me.

The one area of the commerce/submarine struggle where I am somewhat dubious is the apparent ability of the German/Central Powers player to “hop” between the different submarine warfare status boxes whenever he or she wishes. On the one hand, never being certain how “The Hun” is going to tell his U Boat captains to behave from one turn to the next may create genuine game tension, but it does not seem entirely realistic. That is not to say it is entirely wrong. You only have to read the designer’s excellent notes section on the interrelation of factors that led (or in the game, can lead) to US intervention, to see that a very serious level of consideration has been given to this aspect of the design, and that the designer has fully understood the factors in play and has sought to cater for them appropriately. The Germans did embark on unrestricted submarine warfare more than once, and, to put it crudely, could be considered to have “got away with it” for a while. Nevertheless, declaring unrestricted submarine warfare was very much a crossing of the Rubicon, carrying all kinds of political, diplomatic and military consequences beyond the span of the event, and as such “bouncing” alternately and perhaps repeatedly, between the status boxes seems a little too loose for me.

But what must be stressed is that the choice of events for all factions, and the advance of technology, has been well thought out. There has been, by way of “errata,” some further explanation of certain cards beyond their printed instructions, but that is pretty small beer. It is certainly eye-catching in the designer notes as to how many times the decks were computer evaluated to see all was in order. That sort of thing certainly looks impressive, but as a caveat from a technophobe, computers cannot catch the nuances of wording and the aesthetic demands of context, colour and shade. Thus, having mentioned hiccups, while the game has a French Mutiny event card, and I daresay it makes sense within the computations, it nevertheless creates a mutiny irrespective of what has been happening on the map – i.e. the in-game French army could be across the German border against a beaten-up German army when zut alors et quelle domage, the whole lot mutinies…for what? Not likely, but you know what I mean.

But what must be stressed is that the choice of events for all factions, and the advance of technology, has been well thought out. There has been, by way of “errata,” some further explanation of certain cards beyond their printed instructions, but that is pretty small beer. It is certainly eye-catching in the designer notes as to how many times the decks were computer evaluated to see all was in order. That sort of thing certainly looks impressive, but as a caveat from a technophobe, computers cannot catch the nuances of wording and the aesthetic demands of context, colour and shade. Thus, having mentioned hiccups, while the game has a French Mutiny event card, and I daresay it makes sense within the computations, it nevertheless creates a mutiny irrespective of what has been happening on the map – i.e. the in-game French army could be across the German border against a beaten-up German army when zut alors et quelle domage, the whole lot mutinies…for what? Not likely, but you know what I mean.

Nevertheless, the cards very largely make logical sense and do a sound job. There will be no silly and incredible leaps in weaponry for either side, since the technology cards need to be played in appropriate order and are coded as such. But, more importantly perhaps, for those of us who have always felt just a tad uncomfortable about the amazing persistence of the Russians and the prevailing non-appearance of the Americans in Paths of Glory, by contrast things work pretty well in Lamps. There is no absolute guarantee that the Americans will appear, but through what is built into the game, the chances are they will, and for reasons that are perfectly in accord with the actual history – including, as is noted, American finance being fearful of losing all the funds they had poured into the war coffers of the Entente if the Entente then went down in defeat.

Nevertheless, the cards very largely make logical sense and do a sound job. There will be no silly and incredible leaps in weaponry for either side, since the technology cards need to be played in appropriate order and are coded as such. But, more importantly perhaps, for those of us who have always felt just a tad uncomfortable about the amazing persistence of the Russians and the prevailing non-appearance of the Americans in Paths of Glory, by contrast things work pretty well in Lamps. There is no absolute guarantee that the Americans will appear, but through what is built into the game, the chances are they will, and for reasons that are perfectly in accord with the actual history – including, as is noted, American finance being fearful of losing all the funds they had poured into the war coffers of the Entente if the Entente then went down in defeat.

As for Russia, it will not persist. It will decline and wobble in a mild variety of ways, depending on the sequence the relevant cards come out in, and what the situation on the map is as those cards appear. It will, however, collapse, with the Central Powers able to enjoy production advantages as well as the freeing-up of forces formerly committed to the east.

One interesting aspect of this, and something that pertains to the design as a whole, is where the armies of different nationalities get to move. Much of this sort of thing varies from design to design, and if we broaden out this study just for a moment, just as some multi-theatre World War One designs preclude or limit where particular contingents can go, we see the same in any number of World War Two Eastern Front games – Rumanians cannot stack with or sit next to Hungarians, and these plus the Italians cannot deploy on the northern part of the front.

One interesting aspect of this, and something that pertains to the design as a whole, is where the armies of different nationalities get to move. Much of this sort of thing varies from design to design, and if we broaden out this study just for a moment, just as some multi-theatre World War One designs preclude or limit where particular contingents can go, we see the same in any number of World War Two Eastern Front games – Rumanians cannot stack with or sit next to Hungarians, and these plus the Italians cannot deploy on the northern part of the front.

The difficulty with theatre limits or outright prohibitions is that you can always find some historical exception. On the Western Front in WW1, the latter stages of conflict saw a couple of Russian divisions serving on the Entente line, and later a Portuguese division as well. On the German side of things, a handful of Austro-Hungarian units found their way into the trenches south of Verdun. According to some accounts, the Germans would have liked rather more Austro-Hungarian units to bolster the front, but the politics and prevarication of the dying empire got in the way – and even if such as these did not, in the game world, rulebooks often put their own block on things.

In Lamps the block comes in the shape of the rule German Pride. This undoubtedly builds on the premise that the German nation of 1914 had very little time and only varying levels of contempt for most things beyond its borders – including its supposed allies. Thus, there are stringent restrictions on what can enter the German Fatherland, irrespective of how friendly it is meant to be, and this effectively precludes just about any chance that just about anything from the mid or lower Danube is ever going to fight in France.

Not all games do this; Paths of Glory permits Central Powers’ players to adorn the front in the west with whatever the Viennese court has got going spare; but it is all very much a designer’s call, which may part rely on how that designer translates history and potential history into a game, and what the designer may see as the danger of “gaming” his model into some form of absurdity and irrelevance. As ever, there is never one cohesive take on the whole thing.

Anyway, having nudged this study towards the war’s conclusion, and just before we rebound back to its commencement, let me take a look at how victory is determined in Lamps.

To put it in the vernacular of a born Londoner such as myself, by the November of 1918 Germany was knackered. Despite the fact that enemy troops were still to enter any part of Germany proper, the Kaiser’s nation was totally done in. Hitler might subsequently vilify “the men of November 1918,” but that was to conveniently ignore what would have happened in December 1918, or any later month if the war had gone on. In short, there were political crises bordering on all-out revolution, economic meltdown, and starvation.

Without being too much of a seer, much of this could have been predicted in the final months before war broke out. The trouble was, behind all the bluster and arrogance, German leaders at least sensed the precariousness of their situation, which, given their overall paranoia and “now or never” take on things, then helped push them towards war rather than away from it. Germany feared a two front war – and got one. It feared a prolonged war – and got that as well. It feared the Royal Navy and formed an overall naval strategy to cope with it – which did not work from day one. It was terrified that its one continental ally of any significance could fall apart if not supported – it got that right but it all went wrong anyway.

Without being too much of a seer, much of this could have been predicted in the final months before war broke out. The trouble was, behind all the bluster and arrogance, German leaders at least sensed the precariousness of their situation, which, given their overall paranoia and “now or never” take on things, then helped push them towards war rather than away from it. Germany feared a two front war – and got one. It feared a prolonged war – and got that as well. It feared the Royal Navy and formed an overall naval strategy to cope with it – which did not work from day one. It was terrified that its one continental ally of any significance could fall apart if not supported – it got that right but it all went wrong anyway.

Modern scholarship therefore strongly suggests what the game’s victory determination is built on – if the Germans have not won a complete and absolute victory by game end, the Entente wins. Both sides can win early by trouncing the other (essentially amounting to serious territorial acquisition), but the onus is on the Germans to take things, destroy things, and knock major powers out of the contest. To a large extent, the Entente simply has to avoid that, and it will prevail.

Thus, the victory determination in Lamps is deceptively blunt, and in my opinion, does a convincing job in portraying the stark reality of just how big a task Germany and its near senile main European ally faced. Behind all the Germanic strut and swagger as the war began, there was the Kaiser suddenly thinking he need only really fight Russia, and asking his generals about the chances of switching his deploying armies from the west to the east; and somewhere in the vicinity there was Helmuth von Moltke, who was well and truly done in long before Germany itself was…as if he knew more than he was willing to let on.

And staying with these early days of conflict, it is interesting to compare this design with Paths of Glory, with its passing similarity in matters of scale and game engine. However, whereas PoG “stagger starts” its course with shorter calendar turns filled with the same processes as anything coming along later, Lamps goes straight into its seasonal progressions, and whereas you will see a few corps here and there on the PoG map, there are only armies in the Lamps’ rendering of the European fronts. In essence, through area scale and turn scale, nothing visually resembling a “Schlieffen Wheel” is going to show itself in Lamps. Because of the content of the cards that can be played in the war’s opening phase (and let us face it, cards pertaining to history and context is always going to be scripting by another name) you will get a glimpse of the folly and tragedy of 1914, but nothing more than that. PoG gives you a little more scope perhaps, if only in that its rendering of the fronts gives you a bit more wiggle room. But where these two games (or any game with a 1914 context to it) tend to join up is in scripting a credible beginning to proceedings either through card or rule provision – PoG has its “Guns of August” card; Lamps has certain combat advantages (multiple re-rolls) for the Germans first thing; and plenty of games have some variation on the flower of French manhood dashing towards chic endings in white gloves.

What I think Lamps will give you, and this is important, is the sense of the opening phase of the war being about establishing a starting point for future ventures. If you are willing to forget about Schlieffen and his half-used and then wholly used-up fantasy of a plan; if you are ready to forget about Belgian retreats into Antwerp and the “Berthas” around Liege; if you are willing to see your version of a Tannenberg rendered in nothing more than a really good die result or two, the game can give you that sense of setting up a decent first position. Referring back to Molkte, it is worth noting the emphasis modern histories have placed on his seeing the early phase of the campaign as being about setting up some range of modest advantages, and then thinking about what might happen next. The game is not set up in any of its checks and balances to permit either side to wreck the other in double-quick time; it might just happen, but it is very unlikely.

Once the fronts settle and the areas acquire their trenches, progressing your cause will probably involve an inevitable amount of attritional grind coupled with apposite use/arrival of the more important event and technology cards. And maybe, just maybe, those secondary and tertiary fronts might yield a handy advantage along the way. Looking at the two opposing decks of technology cards, both mirror each other in a number of identical progressions, but there are notable differences in the naval context and the final improvement of mobility and firepower on land. On the naval side of things, the tech for the Germans involves getting after the Entente’s commerce, whilst for the Entente, it is getting after the subs getting after the commerce. On land, artillery progressions (essentially looking to “bust up” the trenches) are identical until one reaches the final cards, where the Germans to get their Stosstruppen while the Entente gets the tanks. These final conditions act differently, though both are potent in their own way.

Once the fronts settle and the areas acquire their trenches, progressing your cause will probably involve an inevitable amount of attritional grind coupled with apposite use/arrival of the more important event and technology cards. And maybe, just maybe, those secondary and tertiary fronts might yield a handy advantage along the way. Looking at the two opposing decks of technology cards, both mirror each other in a number of identical progressions, but there are notable differences in the naval context and the final improvement of mobility and firepower on land. On the naval side of things, the tech for the Germans involves getting after the Entente’s commerce, whilst for the Entente, it is getting after the subs getting after the commerce. On land, artillery progressions (essentially looking to “bust up” the trenches) are identical until one reaches the final cards, where the Germans to get their Stosstruppen while the Entente gets the tanks. These final conditions act differently, though both are potent in their own way.

But now, I need to be a bit more controversial than at any point before, for while the game’s technology provisions look sound in concept, and the numerous events are well-founded; while the “sideshow” theatres all have their place and the dreadnoughts either dare or dare not, I was reluctantly left wondering just why the design bothered with armies and areas at all? All the armies fundamentally are is a permission to roll a die and employ a piece of tech; and added to that, with a Western Front likely to be just two areas long, and an Italian front coming in at one area of width, I could be persuaded to see the whole premise of this as misplaced.

Of course, not everyone by any means will see things that way, but I am to some extent, and so are one or two other people whose opinion I value. Given the overall scale, with the fronts largely bereft of any defining feature (being just space in so many cases); with there being no Verdun, Belfort, Ypres, Lodz, Przemysl, Lwow, Isonzo, Chemin des Dames or anything else to fight over; when there is no point d’appui, no sense of “with our backs to the wall;” when all the armies are pretty much the same army; when the game wants us to reflect and understand why East Africa mattered, why the USA entered for reasons that went far beyond what German submarines were doing and one infamous telegram; why then burden the presentment of the big picture with what might be seen as superfluous counter clutter?

It could be that designers, even ones with radical visions, eventually get tied to some hobby conventions perforce – in this case, a map to move units on, and the units themselves to do the moving and the fighting. And yet, the first time I approached the rules to this game, for some hard to pin down reasons it reminded me more of a States of Siege game – a series with next to nothing that resembles conventional units, or a conventional sort of map. Perhaps it was musing over that East Africa track, and the Blockade and U Boat boxes that did it? Perhaps it was also the game’s past history and dalliance with a VPG launch?

In any case, a second reading had me wondering what the armies were doing that the trenches could not do in themselves, and then, with the small fronts and want of the aforementioned “wiggle room,” why a two-area-long front was better than a contested track of relative position and status?

This brings me back to a game very largely overlooked in this little family – that Ted Raicer design mentioned earlier in this piece, The First World War. Why do I refer to this game? Because while many people, thinking of Lamps, may see obvious links to another and far better known and rated Ted Raicer design, Paths of Glory, and while some people may see a few links to the States of Siege series (this is debatable), I do wonder how many people will reference The First World War? And yet, while Lamps does have similarities to aspects of PoG in structure, it is, I believe, far closer to that other Ted Raicer design in elements of concept, scope and general ambition. This makes it all the more regrettable, if you assign any weight to my arguments, that Lamps went with armies and a token acknowledgement of a map of areas to bustle and battle on, when the Raicer map design (essentially a series of front tracks with bad news waiting at either end for whichever side gave way) was a concept waiting to be built on.

This brings me back to a game very largely overlooked in this little family – that Ted Raicer design mentioned earlier in this piece, The First World War. Why do I refer to this game? Because while many people, thinking of Lamps, may see obvious links to another and far better known and rated Ted Raicer design, Paths of Glory, and while some people may see a few links to the States of Siege series (this is debatable), I do wonder how many people will reference The First World War? And yet, while Lamps does have similarities to aspects of PoG in structure, it is, I believe, far closer to that other Ted Raicer design in elements of concept, scope and general ambition. This makes it all the more regrettable, if you assign any weight to my arguments, that Lamps went with armies and a token acknowledgement of a map of areas to bustle and battle on, when the Raicer map design (essentially a series of front tracks with bad news waiting at either end for whichever side gave way) was a concept waiting to be built on.

One complaint I have heard about Lamps is that the army and battle side of things is a chore (to be somewhat caustic you merely pick a succession of army units to pick up and pick a fight for). One of my own contentions is that the fronts lack inherent colour and presence, irrespective of what is on the next upturned card. So why, in any conventional sense, bother with armies and area “fronts” at all? At the level this game largely operates on, winning and losing the war was about having the manpower and resources to endure, and then having the technology to prevail. This could have formed an outstanding small game on a very big theme, and Lamps, to my mind, is nudging in that direction without actually going the whole hog.

So, what am I ultimately doing? Am I saying the game is seriously flawed? No. I am still looking at the work and thinking about things – both the very good and maybe the little less than so. Am I saying that people who do like this game have got it all wrong? Again no, because this designer made the thing he wanted to make, and it will be enjoyed by those who appreciate that particular kind of creative effort – and there are certainly things to commend as well as to debate within this design.

In writing my articles, I have deliberately moved away from any sense of rating games by numbers or stars or anything of the like. Wargames make me think, because they are intense and challenging creative efforts. These are essentially my thoughts on one particular effort.

Paul Comben

——————————————————————————————–

[1] Some readers may wonder about the inclusion of Quartermaster General, which has been highly thought of since its launch. However, in my own opinion, the design is just a little too abstract and “Euro” to make the list – a very fine game, but not really about doing the same sort of job as the others I have listed.

[1] Some readers may wonder about the inclusion of Quartermaster General, which has been highly thought of since its launch. However, in my own opinion, the design is just a little too abstract and “Euro” to make the list – a very fine game, but not really about doing the same sort of job as the others I have listed.

[2] Note: a number of cards put a “reminder” counter on the map to show where and when events and advantages apply.

[3] Again, an element of finessing the issue a little more was missed by me…if by no one else! Frankly, I might have preferred no facility to build new fleets (i.e. resurrect new ones), for while the British and the Germans continued with capital ship building during the war, the sense of any one massive clash being potentially decisive is somewhat lost if you can claw your way back into contention with new ships, and those arriving in unlikely spans of time.

Of course, you could argue that a destroyed fleet unit is actually one full of ships with major damage that have managed to limp back to port. But personally, I really like the idea of a war lost or won in an afternoon, or an evening, or just after breakfast. To that end, the blockade penalties do not seem quite punitive enough, and given the actual final collapse of the German fleet into mutiny, a “use it or lose it” prod to the German player might have been a useful thing to include.

[4] Much the same, together with other factors unique to themselves, could be said of the Ottoman fronts. Colonialism and faded, jaded and occasionally paraded imperial aspirations were at work on both sides, and these sat alongside strategic necessities involving forcing (or preventing) a passage to Russia through the Dardanelles, together with the little matter of oil being a rather handy thing to have in order to fuel those new oil-fired super dreadnoughts.

Games Resources:

The Lamps are Going Out: World War I home page

The Lamps are Going Out: World War I home page

The Lamps are Going Out: World War I BGG page