By Paul Comben

Counter Commands

Administration and Leadership on the Wargame Map

“Now You Are In Command!”

Duke of Wellington in 1814

That was the proud boast on the boxes of the very first Avalon Hill wargames I owned back in 1972/73. And whatever else those games contained by way of somewhat iffy orders of battle and combat mechanisms, they were absolutely bang on in making sure that it really was you who was in command. If there were headquarter/leader units in those games, they were there just to decorate the battlefield: they did not actually do much of anything; they were just there, to be idly shuffled around or plain forgotten about, but never to exert any real influence on events.

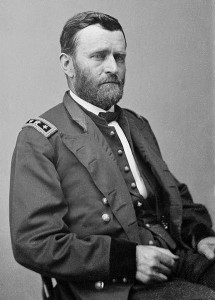

Two of my early treasures were the Avalon Hill classics, Gettysburg (’64 version) and Waterloo. Those games were replete with leader/headquarter units which had no practical function at all. It meant nothing to have Wellington in the front line at Quatre Bras, or to entrust a Confederate assault to units watched over by James Longstreet. You were in command – so, alongside Longstreet’s absolute passivity, as the Union player, you could also be certain Dan Sickles was going to behave himself; and if watching Ney on campaign more than forty five years earlier, he could be trusted to do the French cause no harm, because there was nothing to push the game or any of these decorative ghosts in another direction. Such games did not add a pip to a die roll result for leadership, change an odds column, or, with one exception, make it easier (or harder) to move something to somewhere else. That one small exception came with Afrika Korps, which enabled the Rommel counter to move things that bit faster – but how great or poor leadership could otherwise affect things; how command structures enabled a force to hold together and move to the right place at the right time…or not, these were things still a long way off in the future.

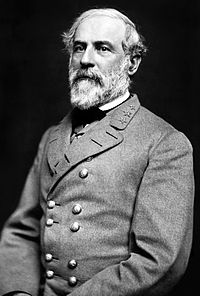

Robert E. Lee

I would not dare to offer a definitive statement as to when a serious look at command, leadership and administration entered the design considerations of individuals and the companies they did work for, as I could hardly claim to have seen everything the hobby produced forty or more years ago. But certainly it was well into the 1970s before I saw a game with anything like a detailed look at battle leadership (Terrible Swift Sword). By contrast, only a couple of years earlier, Avalon Hill had released its game on the American War of Independence, 1776: a detailed work for its time, which nevertheless had no leadership presence at all. There was, so I recall, a variant produced in the pages of The General some time later, which had combat modifiers linked to the historical leaders, but that was certainly not part of the original design.

The first time I saw varying levels of command administration and leadership built into the functions of a game was in the first edition of Kevin Zucker’s Napoleon at Bay, and frankly this opened my eyes to just how incredible the hobby could be when original thinking allied itself to the challenge of presenting historical realities. You were still “in command,” but now, for the first time perhaps, the player got a serious taste of what that meant…utterly realistic frustration – subordinates with no inkling of what to do without a written order in front of them; forces falling to bits the moment you tried to speed them up; battles that could be won, lost, or best avoided altogether depending on the quality of what was written on a desk in a tent beside a nondescript crossroads… wonderful stuff!

I saw another version of this in the early 1990s when The Gamers Civil War Brigade Series started to make an impact. The leaders in this range of games were pretty close to the full package – they issued and received orders; were enthused or confused by what they were told to do; often plain frustrated the hell out of higher ups (the players) by doing nothing at all for hours; or turned many a civil war beard a lighter shade of grey by having an idea all of their own and marching off in entirely the wrong direction. The system was open to abuse, as the gentler voice of command was often avoided by players in the earlier versions of these rules, who preferred to have Bobby Lee barking it out left, right and centre just to make certain Longstreet, Old Blue Light, or Jeb Stuart had got the right idea about what to do and when to do it. Eventually, however, the system put in sanctions for pressing the force button too much (orders could be assigned different levels of force as well as delivered by courier or by what was called an in-person verbal) resulting in a better feel of things. And of course, in addition to this command and order delivery structure, the series also had leaders providing bonuses in battle, exerting a command range, being essential to the rallying of stragglers – in short, as I said earlier, the full package.

One thing I do want to stress, however, is that an absence of leadership or administration/logistic mechanisms is not necessarily to be construed as meaning the game is in any way inferior. In my opinion, game design is at least as much art as science – or at least good design is. Without the art, and what different designers, in the creative moment, are going to pick out as the features of an event they wish to colour and highlight, we are left merely with process. The game I most readily associate with pure function is Avalon Hill’s Tobruk; and whilst that game had its devotees, for many it was an experience which singularly failed to engage the emotions. But on the more positive side of things, if we have had many different takes on Gettysburg, the Battle of the Bulge, North Africa ’41-‘42, it is because we have had so many different designers bringing their own design palette and preference to the shape of great and small events – just like placing three accomplished painters in front of the same landscape, and getting three very different takes on the same scene.

Therefore, we must be cautious: leadership and various finer aspects of command may be “hidden” around the system, or not there at all if the designer has prioritised other things. In a look at how all this works out in practice, I have loosely grouped games by certain definitions which relate to the tiers of campaign and battlefield command. I shall look first at games which either have no obvious leadership or command aspects, or where they are subtly placed – the absent or distant hand. Then, I will look at games which have at least some clear command aspects, and finally at games which provide a serious command and leadership experience.

Easy assumptions need to be avoided, and hopefully readers will be more intrigued towards debate than just perturbed by certain aspects of how things have been done in the hobby. Both of these conditions, assumptions and quandaries, can be found in, or prompted by, games at the grand strategic level. It is not unreasonable to assume, perhaps, that personality is swallowed up and lost as corps and entire armies sweep across the European battlefields of the Second World War. However, whilst John Prados’ Third Reich really did place you in command, with not a leader counter in sight, what do we then say of Mark Herman’s Empire of the Sun, which places the administrative abilities of a whole range of headquarters between you and the ability to move what you want where you want it to go? It may be a long way removed from a tent beside a crossroads, but it amounts to much the same thing. And coming back to the Napoleonic Wars, which stretched over just as much of Europe as the Second World War, it is much more the exception than the rule to find a game on this subject which does not have leaders commanding the forces of all the powers. Napoleon, Kutuzov, Wellington, Davout, Soult… Mack – these and numerous others fill the counter sheets of many a strategic Napoleonic game, and do so for reasons which are integral to the design in question, and are not an optional extra.

As to why we see their like, but not so much Manstein, Bock, Rommel or Patton is surely worthy of interest and debate. Is it the difference between romantic and industrialised war? Is it habit creeping into design? A certain weight of expectation? Whatever individual readers think the answer is, it must surely tackle head on whether there is some fundamental distinction between throwing pencils around in a Berlin or East Prussian bunker, or leading a panzer regiment at Vyazma, as opposed to sitting on a campaign chair waiting for lunch or actually leading a charge of cuirassiers at Borodino.

Now let us look at some games:

1. The Missing, Distant or Unseen Hand.

Having already warned that games minus any obvious command aspect should not be automatically construed as deficient or inferior, let me give some examples of exactly what I mean. Turning Point Stalingrad, (Avalon Hill 1989) was feted by many at the time of its release, and has been generally well regarded ever since. But although, historically, the story of that epic battle included two of the most famous commanders of the Second World War, they never made it into the game. The contrasting natures of von Paulus and Chuikov almost seem to invite inclusion, but the game went elsewhere, and indeed, one can see the deliberate focus of a capable designer and development team in that the original game had the guts to end long before German assaults on the city historically did. This was a system about a Blitzkrieg slowly dying – not what happened when its exponents subsequently turned into the living dead of the Rattenkrieg. For that reason the game’s expansion kit, to take events into the last throes of the historic German attacks, was a bit of a waste of time, and pushed the system into areas it was not ideally suited to.

Who were you in this game? Well, while you may not have had any real sense of the character of Paulus or Chuikov, you certainly had their challenges right there in front of you; and for many players that was sufficient.

Staying on the eastern front, from the venerable Stalingrad to The Russian Campaign to Russian Front, there was nothing by way of clear leadership presence or command structures adding anything to any of these games. However, a distant hand might be sensed in the Ted Raicer design, Barbarossa to Berlin, by way of such a card as the von Paulus Pause, putting a pre-formulated planning break on the eastward surge of the panzers from the distant refuge of the Fuhrer headquarters.

The unseen hand can, by its very nature, seem that bit harder to define, but command and leadership in this context are relevant and are present when, in just about any game, we are pleased/discomforted to get that positive variable reinforcement die roll and when even when some other random event turns in our favour…or not. In short, decisions are being made around us; theatre decisions elsewhere, a higher level command working to our advantage or disadvantage. Yes, we are in command of whatever we have; but then something in the game adds to it, or takes something away, or even stops us in our tracks. Is it enemy action, or do we discern, suspect, a vague shape elsewhere throwing pencils about? So even Turning Point Stalingrad, for all its lack of a von Paulus or Chuikov presence, or any divisional commander or hero of the Guards, is perhaps not so utterly bereft of command leadership hassles, as forces arrive or get taken away, irrespective of what we might want to happen on the map.

Is that it? What about more modern designs which leave out any sense of leadership beyond the merely notional or what might pertain to metaphysical military hands? Well, if we want to look at design as art, and revel in the ensuing range of interpretation, a good place to look is the work of Bowen Simmons – Bonaparte at Marengo/Napoleon’s Triumph/Guns of Gettysburg. These designs have precious little to do with blood and thunder leadership, and a great deal to do with the art of bluff and manoeuvre on battlefields, with units and routines essentially working to an entirely different aesthetic. Some might argue that Napoleon’s Triumph (Austerlitz) does have corps commanders, but they are no more than a presentation and collection device to show the order of the formations in an area – they have no individual characteristics expressed as any form of rating one against another, because Bowen’s eye has picked out something else to highlight; maybe not to everyone’s taste, but certainly to mine.

2. The Leader of the Stack

Within my terms of classification, clear distinctions as to which games fit where are not really possible under any and all circumstances; but to counter that, certain factors do come that bit more into focus when placed alongside something else. So let me just briefly refer back to the “unseen” or “distant” hand shaping events via two very different games on very different subjects. Grand Illusion, covering the early weeks of war on the Western Front in 1914, includes the stipulation for the German player that they cannot initially enter hexes adjacent to the French coast. Meanwhile, whoever is playing the French is initially lumped with having to execute the travesty of Plan 17. This might not strike everyone as a leadership/command presence, but it is – command by Schlieffen, and the embodiment of those misplaced anachronisms behind Plan 17, as well as everyone who tinkered with those plans afterwards, until they were both ready to be unleashed in August 1914. You are in command? Yes, but those vehicles have miles on the clock already, and some naughty and reckless types have been rather heavy on the clutch.

Drive on Stalingrad, hailing back to the days of TSR/SPI, had a serious inclusion of the distant hand – and yes, we are largely back with the pencil chucker again. As the game progressed, the chances increased that the Fuhrer was going to start sticking his oar in, and that in addition to his pencils, with the result that units were going to get stuck or start shifting off in thoroughly awkward directions. In this case, not only has your vehicle got previous history, it has also got a backseat driver with a remote control.

But these are also two games among so many where headquarters and command units have some sort of effect. In Grand Illusion army headquarters help things move and sort themselves out in just another variation of what such units have done over many years in who knows how many designs. For confirmation of this, you only have to look at another game on the same subject, John Gorkowski’s Guns of August, where the various army headquarters carry the artillery assets of the force they command, and need to be up close in order to bring that extra firepower to bear.

Alongside administration and assets, there is personality. It sounds awful, but many games, where one does has functioning headquarters units, there is no sense personality at all. In fact, in this context games tend to split into two camps – those that have headquarters doing some form of administration or support, and those that plump for some form of personality. The most obvious exception to this, that is, designs which possess both administration and the expression of the military personality, is that long line of Kevin Zucker Napoleonic campaign games.

But if we look go forward a century, to look at the game presentation of the armies of 1914, while undoubtedly the personality of commanders played its part in things going the way they did, this does not find its way into the games I have seen. Of course, the designer is always going to have to draw the line somewhere, but in 1914, with you in command, who exactly are you? In a game like Grand Illusion, as the German player, undoubtedly you intend to sweep all before you – but Moltke the Younger, whose job that was supposed to be, never really thought he could do it, and would soon die a completely burnt-out wreck. The Kaiser, whose war this was supposed to be, found himself with more war than he actually wanted and was a bombastic bundle of badly disguised nerves; and at the level of those seven original German army commanders on the Western Front, whose headquarter counters are there on the map, Kluck and Bulow had different ideas of what the great infallible plan meant and literally went their separate ways; whilst over by Verdun, Rupprecht came up with a plan of his own and started demanding forces which were not part of Schlieffen’s priorities – and he, humourless warmonger, had been dead for years anyway.

Vital history no doubt, but does it all fit in a corps level game? In truth, Ted Raicer puts in some of it, and probably as much as the system will take, in terms of changing leaders and progressing the game’s story. But it will not all fit, although it would be fascinating to see someone try.

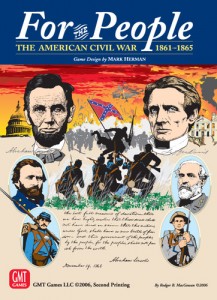

The clean break with the purely headquarters approach is seen with a number of early to mid 19th Century operational and strategic games. Murat and Davout will lead forces across Europe, and Bobby Lee, in Victory Games’ Civil War or GMT’s For the People, will take his Confederate posse of subordinate legends on a march to glory no matter how the game itself finally ends. In designs like these (and of course we can readily add GCACW), the administration of an army is taken as read – and in Lee’s case, that is probably just as well, seeing as how my local fish shop has more staff than his headquarters did. Instead, full of gallant and wonderful combat modifiers, his army tries to end the war with one hard blow, and thus compensate for that allied bunch of zeroes, minuses and next-to- nothings which is supposed to be defending the Mississippi.

Is administration really that out of place in such games? Not entirely, as John Prados’ Army of the Heartland had, as I recall, some reference that area. But it is interesting, as a general trend rather than a concrete principle, that logistics and administration of armies tends to fall out of the design remit the further you go back in time, whereas the lustre of leadership steadily increases. By contrast, the presence of leadership, and its place in designs in all but the purely tactical level, tends to diminish the nearer the modern era you get. The presence of a Manstein/Model counter in The Dark Valley is perhaps some admission as to what has been allowed to drift, as it largely remains the case that one of the greatest generals of the near contemporary era is more likely to be represented by a scenario footnote than a counter actually doing things.

Perhaps the most eloquent example of that design issue comes with the Field Commander series by DVG. These are far from bad games, but I for one struggled to find any sense of Rommel the ever-at-the-front general in the first game (Field Commander Rommel) and only a smattering of Napoleon in the third. By contrast, the Alexander game hit the target for me – his game version led battles; accepted the surrender of cities; looked for omens and sought to fulfill prophecies…in short, the whole tamale. But then, with Alexander, we are back in that heroic era; whereas a Rommel, or, dare I say, a Douglas Haig, is surrounded by wars of a very different kind…or at least we may think so.

3. Character, Communications and Crossroads

To see a leader fully at work, and what works behind a leader, where can we look in a game format? Both the Great Battles of History series and the Musket and Pike series have alike ways in showing how a superior commander can impose his will on the lesser adversary. In essence, the better commander in these designs can choose his moment, and then hit and hit again while the lesser fellow is paralysed with indecision. Furthermore, with the ability to anticipate and dominate often come those other favourable attributes – combat modifiers to bestow advantage at the key point of attack, and morale bonuses to pull muddled formations back together.

But these are games where the battle deployments are often already set, and the field of battle already chosen. In the Gamers/MMP series, the field might already be set, but following the historical path from thereon, even if you want to, is very likely to be frustrated by very historical shortcomings in the ability of such armies to function with absolute reliability. You are in command…but who is listening, who still alive, who looking at the same thing you are? And there are limits on just how many orders you can send out in any period – the more complex, the more supposedly watertight, the longer they will take to put together, with more thinking, and more the need for wearing deliberation or even genius…and not every commander is up to that.

Rudimentary forms of “pulsing” a battle was attempted by Yaquinto in a number of games going back to the late 1970s – Thin Red Line/The Great Redoubt/Pickett’s Charge. The leader combat modifiers worked very much as you would expect, but there was also an initiative rating (optional) to determine who could activate in any given turn. Frankly, after several tries, I could not get decent results with this, and so left it alone. It did not produce anything like a natural pulse on the field, and looked rather like an appended idea, which needed to be worked via a better overall concept.

But in both The Gamers’ series and the work of Kevin Zucker, there is that real sense of administration and planning behind the glory hunting at the front. You are in command, but that also means you must watch the process of formulating an order and its delivery, as well as error and mischance occurring along the way. The reality presented in these designs, is that after all the planning, even the best subordinate may not move in time – think of Stonewall and the Seven Days. And if they do move, but late, honour (integral to The Gamers/MMP approach) may well have them march to destruction rather than offend by thinking again. And of course, the loss of such a subordinate, often little treasures of positive ratings, be it Bagration, Poniatowski, Picton, Jackson, Armistead, will now hurt far more than simply knocking a marker off the map.

This process of turning command into action has received a new level of intensity with the twin games, 1914 Twilight in the East and 1914 Offensive a l’Outrance. I have not seen enough of these games to feel comfortable about making any substantial comment, but it seems that there is a great emphasis placed on army command, putting the players into the process of efficiently turning an order, a plan, into a manoeuvre – basically, if you want to win, plan better (and execute quicker) than the opponent. Here is a truth: not all superiority, all advantages, can be expressed in combat factors or movement allowances. The ability of one army to outwork, out plan, out anticipate another, is something true to many ages of warfare; and in that context, going back through the centuries, I rather doubt if Alexander or Caesar prevailed on campaign simply by what they carried around in their heads. There too, there would have been a tent beside a crossroads, and a lot of writing going on.

In putting this article together I am very much aware that, for every example I have given, there were scores more I could have cited if space allowed. Tactical leadership in series like ASL I have not really touched. What I hope I have done is given a sense of what command can add to a game, and invite readers to ponder where more could be done. I am also aware of whole areas of simulation where leadership has yet to find an effective game format. We may paint poetic pictures and assign splendid ratings to a Nelson counter at Trafalgar; but what made Nelson great was what he did before a battle, not during it; for the plan was already set by then.

And where then Jellicoe? Where Hipper? Tovey in the North Atlantic in 1941, Halsey in the Pacific in 1942? Where does Dowding fit into a Battle of Britain design? Somewhere or nowhere? Where are their staff? Does it matter? Of course it does. Personality can sway events to a vast degree. If Manstein had been in the pocket at Stalingrad, there would have been no surrender of a dwindling army, because no one who could march would have been there past December, irrespective of where the pencils went flying. Leadership and everything it is attached to really matters – and it cannot just continually be forgotten about, played down or paid lip service, or merely consigned to a footnote.