By Paul Comben

Grand Tactical Interpretations of Quatre Bras

Part I

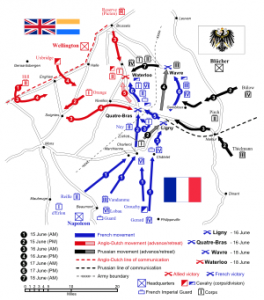

It was not long after the ordeal of Waterloo that Wellington’s diminished but triumphant Anglo-Dutch army returned to the site of its first trial in this bloodily short campaign – the field of Quatre Bras. Although a much smaller battle than Waterloo, and like everything else that pertains to The Hundred Days, forever in Waterloo’s mighty shadow, Quatre Bras had been a vicious dogfight, full of drama, full of missed opportunities and strokes of fortune, and, to no inconsiderable extent, the shaper of events that would unfold just a few miles to the north only two days later.

From the board wargaming perspective, Quatre Bras, with its more limited field, smaller armies, and liberal amount of historical colour, makes an ideal candidate for intense study and the evaluation of systems that have turned their attention its way. The engagement that was fought on the afternoon and into the evening of June 16th 1815 has indeed been the subject of numerous games over the years – some, scenarios plucked from bigger campaign projects, or from four- battle packages, such as Napoleon’s Last Battles, The Battles of Waterloo, and the far more recent Le Retour de L’Empreur. More is likely to be seen of Quatre Bras in this bi-centennial year, but as things stand, at the Grand Tactical level, we have just the two designs, and these of considerable vintage.

Ney versus Wellington and La Bataille des Quatre Bras have one thing in common apart from their subject matter, and that is how far back we can trace their beginnings. Both, of course, are derived from what were pre-existing systems – Wellington’s Victory for Ney versus Wellington, and what has become the extensive (and this is important, evolving) La Bataille family for the Clash of Arms Quatre Bras. This essentially takes us back to the mid-1970s, when the original version of Wellington’s Victory, and the first edition of La Bataille de la Moskawa, were making their own far from faint impression on the hobby. As many readers will be aware, the Wellington’s Victory system had a relatively short life in terms of subsequent titles – Ney versus Wellington and The Battle of Monmouth being the entire story. By contrast, La Bataille has produced numerous titles across the range of Napoleonic conflict, and in the course of its evolution, has become closer to a notion of “art” within the hobby than just about anything else.

What I intend to do in this article is broadly trace the story of the Quatre Bras battle, and at each stage, look at how the two systems deal with those aspects under consideration. This does not mean I will be going through the rulebooks paragraph by paragraph; rather, I will be concentrating on the “feel” of the designs as they tackle (or fail to tackle) the salient issues. What I am driving at here is that while we all play wargames to explore the potential of situations and dwell among the what-ifs, it remains a good measure of a design as to whether it can recreate the actual events of the battle/campaign in question – even if we really do not want them to! If it cannot, or does so in some awkward or contrived way, then something is clearly amiss.

In another Hundred Days article, I described the Napoleonic model presented in the Wellington’s Victory system as being indicative of a “process” game. By this I meant that the game was almost entirely about the function of force and formation on the given Napoleonic battlefield – a game of calculation and science over any real notion of colour. By contrast, from the presentation of the counters to the style of the maps, and even the inclusion of French terms for aspects of maneuver and assault on the field of honour, La Bataille has sought, sometimes regardless of the practicalities, to do things with a higher aesthetic value. This is not to be construed as a criticism of either approach – rather, within the remit of this article, it should be seen as something that adds a real edge to the study, and to that I will say here and now that both systems are pieces of work worthy of respect… not perfect, but what else in the hobby is?

The Battle of Quatre Bras – The Preliminaries

One thing separates this battle from any other engagement in Wellington’s career as a commander – he did not choose the field. In the time leading up to the period of active campaigning in Belgium, the Duke had several potential battle sites surveyed, including full engineering studies of the Mont St Jean ridge and the area around Hal. In other words, whichever way Napoleon came into Belgium, Wellington wanted an evaluated battlefield to meet him on. Quatre Bras was not a major part of the calculation, given that the “gravity” of his concerns had pulled his attention further to the west and his communications across the Channel. Likewise Blücher had been casting much the same sort of eye for much the same reason eastwards towards the Rhine. Thus, the advance of the left wing of L’Armée du Nord towards the crossroads of Quatre Bras, found Wellington’s army still scattered over a wide area, and with very little positioned at the hamlet crossroads itself.

Nevertheless, although Quatre Bras was not a typical Wellington position, it did have a few traits in common with the area immediately south of Mont St Jean. These included enclosed farm buildings on the approaches to the main line of defence (most notably Grand Pierrepont and Gémoincourt), as well as a scattering of sunken roads and lanes. The countryside thereabouts can be readily described as “rolling,” but there was not any true “reverse slope” position for the Duke’s forces to take post on. Two other things were literally staring the combatants in the face, one of which both games cover (they could hardly dare not to and still be taken seriously) and the other one Ney versus Wellington seems to have avoided like the plague. Readily present on both maps, the Bois de Bossu was a substantial piece of woodland extending across what would become the right of Wellington’s line. Its southwestern extremity was bounded by a sizeable orchard, which is readily visible in the La Bataille version, but almost (but not entirely) covered by the tables and tracks about the periphery of the Ney versus Wellington map.

However, entirely missing from the Ney versus Wellington map and rules is the incredibly tall and extensive fields of rye and other cereal crops established about the area. Accounts over many years, including the words of soldiers who fought in the battle, speak of a towering crop over seven feet high, which certainly had an effect on units trying to deploy and ascertain what they had in front of them. From the design perspective, it is not too difficult to deduce reasons why all this growth never made it into the SPI game (what do you do with the functionality of map, and what can you make, from a 1970’s design outlook, of the crop’s effects that will not clog the design?). By contrast, La Bataille’s Quatre Bras has a relatively straightforward (though optional) rule for obscuring units setting up in the fields. This is okay as far as it goes, but as it does not apply to units arriving after the scenario start, and as it is all about confusing the French rather than affording any nasty surprise to the Anglo-Dutch forces (some of whom were, on the day, caught meandering around with hostile and hard to see cavalry looming close) it is perhaps not all that it could be.

As to what else is actually on the maps, and these being maps that are essentially at the same scale (about 100 yards/metres per hex), there are certain differences presented in the length of particular sunken lanes, but never drastically so, as well as variance in the presentation of walled farms, especially when comparing Ney versus Wellington to its own ancestor. In the parent title, La Haie Sainte and Hougomont both had several utterly impassable (“walled”) hexsides, whereas the walled farms in Ney versus Wellington are simply presented as generic building/village hexes. La Bataille, on the other hand, has them depicted as the enclosed “mini fortresses” they were. How this all plays out in the actual battle recreations we shall see a little later.

When it comes to Line of Sight, even if we just leave the crops out of it, the systems still diverge considerably. To offer a personal opinion on LoS issues, I would always go with a big dose of common sense, even “winging it/fudging it,” call it what you will, rather than having the gameplay descend into a mess of disputes and misinterpretation. There is, however, nothing in the La Bataille version that should cause any real problem, and especially if you have the rules from the most up-to-date Quatre Bras edition – the Third Edition rules, on the other hand, could have you in a state of distraction well before you ever got to explanations as to who can see what. By contrast, the Ney versus Wellington LoS rules are long, complex, and rather off-putting. In seeking to present series maps of rolling contours and gradients, the LoS aspect of the rules ended up being filled with bits of mathematical equation more at home in a college textbook. The basic premise was simple enough – are you on top of a slope, on the reverse or the front side, and what else is getting in the way of your cannonball? Frankly, for me, this was when the process of the game got particularly oppressive, so I ignored it, played it with a bit of common savvy, and looked to enjoy the better things the game had to offer.

Overall, you should find, like me, that the maps do convey a sense of the ethos behind the designs. Ney versus Wellington is largely about stark functionality as well as reflecting “the wargame mode” of nearly forty years ago. La Bataille has its period-style, hand-drawn look helping to set the scene and create the mood – though had its place in the series been nearer its origin, it might well have come with NATO symbols adorning the pieces. As it is, the counter graphics to both designs reflect the changing way of things: the Ney versus Wellington pieces are clear, functional, but would never win a design prize today, whereas La Bataille units sit close to the extremities of “art for art’s sake,” as much of the most vital information is hidden on the reverse side, allowing room on the front for those intimations of uniformed splendor the genteel ladies would be pearling their eyes over.

One last thing to mention before when get to the battle proper is the sequence of play for both games: Wellington’s Victory was the first game I encountered with an asymmetrical play sequence, and outside of this series, I have not really encountered its like again. This was more than the designer simply adopting change for change’s sake, as it was built upon the logic of giving Wellington (i.e. the player) the advantage of his ridge position and his inherent ability as an outstanding commander on the defensive. Basically, the way the sequence was ordered, whatever the French player had brewing by way of massing this and moving/charging with that, the Anglo-Dutch forces had some opportunity to respond to before threat turned into reality. And although Quatre Bras put the Duke’s army in a much less advantageous position, the Duke was still there, and that in itself was probably sufficient to keep the original play sequence intact for the later game.

As for La Bataille, we are back to a comfortable symmetry, with formation change, movement and combat where you would expect them to be – but always, throughout the series, with the insistence that the French move first.

The Battle Begins

By the time Ney finally bestirred himself to launch his attack towards the strategically vital crossroads, the afternoon of June 16th was already well advanced. Ney versus Wellington begins at this moment, with the French columns about to press on the thin Allied line. The Clash of Arms game begins earlier, with the French forces still advancing from Frasnes – note: the Clash of Arms Quatre Bras has a map that is rather more South to North than East to West.

However, despite the greater time scope of this game, including a nice piece of colour regarding the late arrival and on the spot “crisis management” of the Duke, it is hard to escape the feeling that some major design opportunities have been missed. Given that we have a welcome representation of Wellington hastening to the battle, and sufficient preliminary time for the French player to evolve a different approach and pace to the subsequent engagement, it is hard to understand why no real effort was made to do something special with the inviting game canvas that is Marshal Ney.

For all the touches around issues of tall crops and Wellington galloping back from Ligny, so much of what happened at Quatre Bras was linked to the odd goings-on in the brain of Michel Ney. It is all very well varying the arrival of Wellington’s reinforcements (actually, no it is not – more anon) and concealing what is where at the start, but throughout the battle, the struggle was very much driven by Ney’s wildly varying perceptions as to what was going on and whether he was winning, losing…or needing to try harder. I will come to the treatment of the French I Corps in due course, but will state here that I think it was an error to set hard and fast victory conditions, as that very fact helps to blow the fog out of Ney’s head – which, from the point of view of setting a true stage for the bloody play of affairs, is the last thing you want to do.

But whatever the prelude does or does not do, the first challenge facing the French troops of Reille’s II Corps on both maps is likely to be clearing the forward Dutch-Belgian forces from those outlying fortress farmyards. Reading between the lines (or peering between the stalks), there are indications/inklings in both games that rules provisions for this sort of situation took some sorting out. On the day, the fight for these bastions gave the first indication that the Dutch-Belgian troops were ready to put up a fight. However, with both models built largely on the premise that unformed/disordered units are bad news, and that anything other than open, uncluttered country is a bad place to be for the neatness and efficiency of your battalions, reversing all that to present determined stands behind farmer Jacque’s pigsty seems to have proved a bit of a challenge.

Looking at the most recent series and specific rules for Clash of Arms’ Quatre Bras, the short but highly effective paragraph dealing with infantry units in “Grande Ferme” hexes is shaded grey – indicating a revision from the last time around. The solution is perfectly simple: treat the unit as in square; discount just about all the negatives for supposedly being disordered among the muck, ducks and manure; up the fire defence strength by a considerable margin; and do not allow more than a portion of any assaulting force’s strength to be included in an assault calculation – not everyone, after all, can be climbing over a wall at the same time, or squeezing through a half open gate. Thus, even what is meant to be lowly Dutch militia has a serious chance to make a courageous showing.

With Ney versus Wellington, I suspect the provision for this sort of situation never really settled down into something everyone understood and could work happily with. The system is so immersed in the iron regulations of formation use, that trying to do something sound in a situation that is supposed to be bad is not readily addressed. Trying to enter that game world, you never get the sense that having four walls around you and a roof over your head is going to make you feel more safe and secure than confused and ready to run off. In Wellington’s Victory you never really wanted, or by rule were commended, to put a battalion unit of infantry in a chateau or farm building – by consequence your unit would be disordered and subject to other negatives that the rules did little to allay. A recent question on BGG highlighted the uncertainty; for while the system more than inferred that the only thing to put into strongpoints were skirmisher units, it was hard to see where their intrepid fortitude and resilience were meant to come from. It really was a case of the system only begrudgingly yielding a few unremarkable advantages to forces, which historically, held these positions for a considerable number of battle hours. I would actually recommend taking the example of the Clash of Arms rule and simply adapting it to the Ney versus Wellington environment. Then again, perhaps the revised new version of Wellington’s Victory will tidy all this up…perhaps.

Back at the battle, even as the French were pressing against the farms, the first contingents of Wellington’s Reserve Corps were approaching the crossroads after the march south from Brussels. Picton’s division was in the lead, followed by the Brunswickers, who were urged on by their pipe-smoking casualty-waiting-to-happen, duke. This is what Wellington expected to see, and this is precisely what he got. But in the La Bataille version, you might get something else at some other time. While this sounds like just the sort of thing to throw into the mix, to my mind it is not the right approach. To be blunt, it cuts the Duke right out of the ordering of his own reinforcements – reinforcements which had, in reality, been sent on their way via clear orders issued whilst everyone was still present at the Duchess of Richmond’s ball.

Again, where the variability and confusion really belong is with Ney. The wanderings of D’Erlon’s corps helped to frustrate and bewilder him to the point of incandescent fury. He showed precious little appreciation of the overall campaign plan, or nuancing thereof, within which context simply holding his own and letting D’Erlon go on his way was far better than the “sulks in the sweetshop” approach to military planning he was lapsing into. As for the small reinforcement he did avail himself of (part of Kellerman corps of cavalry), far from being any sort of scheduled arrival, it was more a question of a fuming Frenchman looking here and there for anything he could grab hold of and throwing it into the fray.

This is not difficult stuff to model: imagine at Ney’s emotional state being represented on an ascending track, with the marker moving up if the Marshal of France has failed to capture the crossroads by a certain time, has seen D’Erlon drift off, or more Allied reinforcements arriving. The higher the track, the more likely Ney will try and grab D’Erlon back (losing victory points), or start using the forces the emperor told him to leave alone, or launch a foolhardy attack akin to those found on the Hood table in The Gamer’s “Embrace An Angry Wind.” Why not give it a go?

As for Ney versus Wellington, everything arrives precisely when it did, which, after the criticism I have made of the game thus far, might well sound like I am now damning it with faint praise. The best aspects of that system, is in the interrelation of force types and formation – which, if I recall correctly, the design notes of the day highlighted as a key aspect of how the game shaped up. And with that in mind, anyone approaching this system needs to be careful not to pick off too many aspects of any one game mechanism without seeing how it links to what is going on around it. But I am willing to make one more exception here, and that is in the context of the presentation and use of skirmisher units in the two systems.

On the face of it, the way the skirmishers are handled in Ney versus Wellington appears perfectly acceptable, and certainly, for the most part, it works. As was the historical case, French/Allied light infantry regiments can transform into the proverbial cloud of tirailleurs/jaegers/light companies and riflemen, whilst adding to the hostile overcast, full strength French/Allied infantry line battalions, can release a company-strength unit to act the same way – and with exactly the same values and attributes as their légere/jaeger/light company comrades. Certainly, this sort of provision can produce a substantial belt of potshot adepts, but that is also where the problems begin. One criticism of the approach this system took was, and is, that it standardized matters a bit too much – the strength of formations was evened out, and skirmishers, French, Coalition, from light regiments or from anything else of at least average effectiveness (militia/landwehr could not detach skirmishers) were all rated 1:5:5 – 100 men, level 5 effectiveness, and 5 movements points to dash about with.

In all likelihood not everyone will agree with me on this, but I found this both a bit bland and mechanically oppressive. Why every skirmish company got into battle in exactly the same good mood, and how I was supposed to enjoy myself having to roll resolution dice here, there and everywhere for the lot of them, was quite beyond me. Furthermore, I was not the only player who thought they were too much of a power on the battlefield, and should have been a little more restricted in their usage. Of course, you could hardly leave them out altogether, in what was meant to be a grand tactical system; although interestingly, La Bataille does go halfway towards that. There, only the elite light regiments, or Allied battalions with genuine elite companies, can sent out skirmishers, with a bit of extra game seasoning in the ability of certain cavalry regiments (those given a firepower factor) to act as mounted screens and harassers of enemy forces.

What was intended by the La Bataille approach, I am guessing, was part a desire to keep down clutter and clogging in the gameplay, yet also a statement of design outlook that saw the broader mass of “base, common and popular” skirmishers as being far more puff than bang and therefore not worth including. Overall, I think there are issues with both approaches, and will offer my own alternative (for what it is worth) in a moment. Just before that, however, it is worth taking one last look at this skirmisher aspect of the old SPI design just to glean a bit of honest-to-goodness gaming history from it. If we do consider the Wellington’s Victory system flawed at this point, and a bit too fussy and mechanically overbearing, let us remember not only the short evolutionary story of the series (actually, it hardly evolved at all), but also that long ago time when the series was making its appearance.

I recall the mid-1970s as an era in the hobby when people had a fascination about seeing just how realistic, and big, and “all thing’s in,” designs could actually get. Realism and sheer bigness seemed to troop along together, and no one seemed to think that much as to how playable the end result would be. Indeed, I well recall a humorous piece in The General from about that same time, wherein a friend of a wargaming fanatic visits his home and finds him in the midst of setting up “It,” a game covering World War Two in Europe at a scale of one unit equals one man/tank/plane etc. Perhaps no one should be surprised then that Wellington’s Victory wanted its take on big, broad, and all-in – it was more than just the system model, but truly a reflection of the time.

Nevertheless, it might seem rich coming from me, that after talking about the measure of a game being partly its ability to recreate the historical pattern, I then start criticizing a game for essentially doing, or seeking to do, exactly that. In response, I would still insist that I do want the historical whys and wherefores present, but in my mind that does not mean committing the resultant model to fiddly minutiae. Thinking of all those Hundred Days battle maps I have seen, with lines of skirmishers extending over the entire front, I am given to wonder if the effect of skirmishers could be presented without having any such unit on the game map? If skirmishers were ubiquitous, so was the mud at Waterloo and the rye (again!) at Quatre Bras. But we do not have muddy puddles all over the Waterloo map, or the tall crop printed around Quatre Bras – the effect is in the rules. Why not the same for skirmishers? Maybe you keep the absolute elite companies on the map for the really important stuff, but otherwise just have a skirmisher effects table – roll a die each turn and see if you can inflict a couple of free hits on the enemy; or be shielded from the same; or knock out a battery; or have a chance of putting a ball into the body of some unfortunate senior officer. No clutter, no fuss, and job done.

But whichever way skirmishers are presented, there can be no doubt that a fair number of the combatants at Quatre Bras fought in far looser formations than would have been considered appropriate in other circumstances. A major reason for this was the Bois de Bossu, which was entered by troops from Jerome’s 6th French division in the aftermath of the Allied outlying positions being cleared and the Dutch-Belgian forces falling further back. It is important to note that the weight of the overall French effort constantly remained more to the east throughout the battle, where commanders were able to find a platform for their artillery, room for their cavalry (not that there was much cavalry about), and where the so important Namur road ran north of the Materne pond and thus on towards the Ligny battlefield roughly seven miles distant.

Even before the fighting actually began, Bossu had put a brake on French intentions. Ney apparently feared what might be lurking within, and this helped delay the French advance. Furthermore, once the fight was underway, Ney and Reille could hardly ignore the wood, which ran along much of their left flank and close to the Brussels road; and so Bauduin and Soye’s brigades of Jerome’s division were sent into the trees. Ironically, these troops, and those who would oppose them later in the day, the British Guards, would be matched up again in and around the Hougomont woods just two days later.

In both systems, putting a formed infantry battalion into woods causes a change of formation state – Disorder in Ney versus Wellington, General Order in La Bataille. Troop capacities in such hexes are less in both games than for clear terrain, and are best described as one battalion unless losses permit more units to make up the same total figure – 9 (900 men) in Ney versus Wellington, and 10 (1,000 men) in La Bataille. Both systems hold to a figure of 1,800 infantry for a clear hex. Fire combat, as one might expect, given the trees and the dispersion of force, is seriously ineffective – in both systems a one in six chance of inflicting a one point loss. As for melee/shock, in a situation where there are trees and diverse other forms of vegetation all over the place, the notion that melee purely applies to massed bayonet charges or anything that brings soldiers to the hurly-burly of hand to hand combat must be qualified. Inevitably, there is still going to be musketry at these short ranges, and it is probably the case that it will be more the show of resolve (i.e. unit morale/effectiveness ratings) and the commensurate power to endure longer than the opponent that will decide a combat fought within the time span of a game turn.

When it comes to how the two systems turn all this into game mechanisms, one might summarize the differences here by asking if you want a two act showdown or something more elaborate? Both systems come to essentially the same conclusion, the same effect, but do so via markedly different means. In Ney versus Wellington you add up the strengths, throw in the top unit’s effectiveness rating, find the right column for the resolution, and roll the die. Of course, it is a bit more complex than that, but not overly so – note: cavalry for both systems is another matter entirely, and is addressed later. By contrast, when it comes to infantry assaults in La Bataille, the game wants you to feel the drama of the drums beating the Pas de Charge, the “Huzzah!” of the British line going forward with bayonets gleaming…and, as one might possibly imagine, Ney falling off his horse. Where the Wellington’s Victory system takes a number of things as read when it comes to infantry melee, La Bataille takes you through the process, and presents it very much as a several part psychological showdown. The attackers must show a willingness to close; the defenders must then show a willingness to stand, or, should they wish, a capacity to clear out in decent order; and then, and only then, if one side is closing and the other side standing, do you get to the question of material hurt.

If there is an actual melee, both systems have their resolution tables; but here, quite apart from the different formatting of the tables concerned, there is a notable difference in the range of results. Overall, both tables do stress running off, retreating and routing far more than the spilling of blood, but in La Bataille, there is a notable provision of bloodshed at lower odds attacks. In extreme cases, up to three or four points of loss can be suffered from the table, whereas, at the same moderate odds levels in the SPI model, losing two points is a rarity and is the product of a rout occurring. I am not going to express an opinion as to which system tells the better, more realistic story, as there is logic behind everything – though again, La Bataille has the colour. What is pretty obvious from the La Bataille table is an interpretation of numerical results (your actual losses) being representative of fights where neither side gives way and the tussle is going on longer. The lack of “blood” results at the higher odds levels probably reflect one side hopping it as a result of being materially or psychologically overwhelmed, even if they determined to stand in the first place.

The Battle for the Crossroads

Having arrived, Picton and Brunswick were thrown straight into action. The Brunswickers were deployed around the hamlet itself, whilst Picton’s brigades turned east and moved along the sunken Namur road. However, accounts make it clear that a good deal of the time, Picton’s forces were immediately south of the road rather than clinging to the moderate shelter of the chaussée itself. These same accounts do not really spell out why the 5th division’s regiments were not entirely deployed within the only protection around, but both games offer answers via what can be gleaned from the play experience. If we look at the Ney versus Wellington map, its attention to the lie of the land tells us some very important things Firstly, that Anglo-Allied artillery had to be deployed forward to get anything like a field of fire, and with the small number of Anglo-Allied batteries thus deployed, there was a need for them to be protected. A substantial portion of the Namur road was on a mild reverse slope – great for protecting the men with the muskets, but no good for sending destruction out to six hundred to eight hundred yards.

Furthermore, owing to the “grain” of the battle area (no, not the rye in this case!), if Picton’s forces had clung to the road, they would have been out of alignment with the Brunswickers, who were forward (south) of the Quatre Bras crossroads as their natural defensive position. The consequences of this are made clear simply by looking at any map of the battle, or, as in my case, a satellite view. Holding to the line of the road would have put the eastern end of Wellington’s line pointing diagonally ahead of the rest of the position, and have afforded an awkward field of fire pointing at much of its own army.

French Cuirassiers attacking the Black Watch (42nd Highlanders) at the Battle of Quatre Bras by William Barnes Wollen

But that is not the only thing these games have to tell us about how the battle progressed at this stage. With only a relatively small cavalry force present, the French were nevertheless able to launch some very menacing cavalry attacks which resulted in far more discomfort for Wellington’s forces than anything cavalry alone inflicted on those same forces just two days later. In this context, clinging to the road was a recipe for further disaster, for, as the games tell us, you cannot form square in a sunken road hex. Lose track of this, and those two rank lines you thought to keep relatively intact along the chaussée run the risk of being cut to pieces.

Overall, this is one situation where I think Ney versus Wellington has a bit of an edge on La Bataille, at least as far as this battle is concerned. The La Bataille map is a lovely piece of work, but does not have the geographical subtlety of the SPI map. Things are somewhat evened out – mild slopes are there, but they are purely decorative, and thus who should or should not be able to see what from any given point along that road may be a tad compromised.

Neither Ney or Wellington’s army had bucket-loads of artillery, but, as ever, the French artillery was a dangerous and daring force. Both games give the French the divisional batteries of Bachelu’s, Foy’s and Jerome’s divisions, plus their corps battery of twelve pounders and Pire’s artillery battery. Conspicuously missing is the horse artillery of the Guard Light Division. Of course, Napoleon had more or less drummed it into Ney’s head that he was not to use this force for anything arduous – he could look at it, move it around a bit, but it was meant to be kept fresh for the intended night march on Brussels. This, of course, does not sit comfortably with Ney versus Wellington handing out an entire regiment of Guard Lancers to do with as you please. On the other hand, recent accounts of the battle, and that especially means Tim Clayton’s book, rather suggest that not all the cavalry assets that should have been banging about the field made it into the games. Clayton cites (Waterloo: Chapter 23 Note 2) contemporary sources whose testimony suggests that the Guard Light Division did at least have its artillery in action at Quatre Bras.

This possible employment certainly fits French artillery ethos; that guns from whatever formation source could be melded into a larger/grand battery for whatever purpose. But irrespective of whether the French had this or that number of artillery pieces, there are a few other things worthy of mentioning in connection to game usages of cannon. In La Bataille, getting unlimbered artillery ready to move is far from automatic, though it is easier for French batteries, reflecting the training and aggressive élan of the arm. But for the Anglo-Allied player, siting artillery should be done with that bit extra care, as it is likely to become a semi-permanent feature of that hex once it is deployed.

With the Wellington’s Victory system, a major change from the parent title to Ney versus Wellington was the removal of the artillery crew counters. I rather suspect this had a lot to do with Ney versus Wellington being a Strategy & Tactics game, and there was no room on the counter sheet. Then again, the crews were another bit of clutter the system could do without, and their absence in the Quatre Bras game makes absolutely no difference to play whatsoever. Also missing is the restriction on limbering batteries, but if you wish to use it with the SPI games, the Clash of Arms rules are eminently transferable.

One thing that should have been factored in to both designs, but is only in one (La Bataille), and that only in its more recent forms, is the amount of baggage (literally) any battery brings with it. In the Mark Adkin “Waterloo Companion,” there is a telling diagrammatic layout of the French Grand battery set up in the early stages of the June 18th battle. Basically, behind the deployed guns, there was a deep belt of caissons, limbers and other impedimenta that formed a very serious obstacle to formed troops. Again, more recent accounts of Waterloo offer up evidence that games designers should be interested in bringing to their work. In particular, the eighty-plus guns deployed against the left-centre of Wellington’s line caused such an obstruction that at least two (or possibly three) of the four infantry divisions of D’Erlon’s corps swerved around the eastern end of the gun line rather than try and pick their way through it. Even a couple of batteries can make a fair barrier, yet the Wellington’s Victory/Ney versus Wellington model has nothing beyond some stacking provisions to cover the issue of infantry passing through artillery. I suspect that this really is not enough, given that the moment you send a battalion through so much as a scrap of woodland things start to shake loose.

At this stage of the battle Picton’s forces launched a limited counterattack. But with next to no cavalry to set against the French mounted forces, to go any distance was to invite disaster. As it was, a French cavalry attack against the Brunswickers led to Picton’s line being compromised as its right flank was exposed – there you are, should have stayed in the road! This provoked one of the battle’s several crises, and gives me the excuse to introduce the command systems of the two games.

Ney versus Wellington…whether we are looking at the game that bears that very title, or at the Clash of Arms game, it is hard to think of a more complete contrast of command character than possessed these two gentlemen. Whatever might be thrown at Ney for his failures in the 1815 campaign, he had certainly had his glory and achievement in the past. His name is forever linked to the terrible retreat of 1812, where his desperate rearguard actions were the one aspect of that disaster where a sense of glory might still be claimed. But studies suggest that it all had a calamitous effect on Ney, with the argument being that the experience left him psychologically wrecked. Whether it did or not, Ney had ever been a quick tempered, brash, brave and aggressive fighting general, who was at his best when told what to attack or what to defend; but when it came to any amount of creative planning or astute interpretation of a complex situation, he was seriously out of his depth.

In this light, the last person he needed to be pitted against was Wellington. The Duke was certainly an emotional man, but like U.S. Grant, was able to contain those emotions until the business of the day was complete. If one desires material proof of just how collected the Duke was on the field of battle, look no further than the orders he composed in the very heat of Waterloo. Written in pencil on pieces of prepared hide, the surviving examples display an absolute clarity of thought and equanimity of temper. In the early stages of Quatre Bras, Wellington’s forces were outnumbered and hard pressed, but he never lost control of the situation – or of himself. The one thing he had in common with Ney was that he led from the front. Throughout the campaign he was up with the fighting regiments, narrowly escaping a group of French cavalry at Quatre Bras and having numerous members of his staff fall about him at Waterloo. It is also interesting to compare the reaction of troops who found either Ney or Wellington close by – exuberant French acclaim and élan contrasting with the command of more than a few British sergeants: “Silence! Look to your front. The Duke!”

There was one other difference between the two men in that brief 1815 campaign, which one might look to see reflected in the right sort of game simulation: he may have lost many a colleague and friend at Waterloo, but Wellington entered the campaign with a fully functioning staff; as for Ney, galloping after Napoleon and L’Armée du Nord even on the very brink of actual hostilities, he had practically no staff at all. To put a staff together, Ney had to grab anyone to hand and hope they had some inkling of a staff officer’s job. This was in turn part of what unraveled for Napoleon in Belgium, and Napoleon had no one to blame for that but himself. On Saint Helena he admitted that a number of his appointments in 1815 were the wrong choices – Grouchy was no wing commander, and neither was Ney; Vandamme, the opinionated curmudgeon, was a bad choice for corps command given a campaign plan that required speed of execution; Soult wrote out some disastrously vague orders; and Suchet, aggressive and capable, was left criminally unemployed.

In numerous games of the Napoleonic era, at whatever scale, there have been a variety of mechanisms employed to create command frustrations or to highlight the qualities of better command abilities over those that can be readily deemed as inferior. In some there is chit pull, in others command tables, and some take you through the process of writing orders and issuing them (or trying to) to subordinates. In the SPI games, it would have to be said that the vintage of the designs puts their mechanisms at a point before all of this kind of stuff became de rigueur – not that it has ever been entirely that to this day. Thus, in the SPI series, you get some very mild stacking benefits for having a leader present, and those same leaders can help with a morale check if the unit in question lies within command radius…and that is pretty close to being it. There is no actual issuing of orders, keeping calm or blowing up – every last unit in a non-routed condition will move when and where you want it to…no funny moods, no getting the jump on the opponent, no misinterpretation.

I am trusting my memory here as much as anything, but I think I am right in saying that the La Bataille family did not have much more to say on the subject for a fair number of years – and no surprise there maybe, when the origins of that series go back to the same time as Wellington’s Victory. My first encounter with “the family” was in the early 1980s, when I got the GDW version of La Bataille de la Moskowa. It was certainly a different system to what I had seen in the SPI range, but, by and large, it was impressive more because it was big, and not because it was some stunningly innovative work of genius.

What qualities that same family possesses today are in no small way thanks to the series having been allowed to go on rather than “doing a General Mack” – i.e. getting cut off and isolated. Perhaps the SPI series would have evolved under different circumstances; and while it is there asking for attention, the new Wellington’s Victory, yet to see the light of day, remains a bit of an enigma. Of that forthcoming revamp all I will commit myself to saying is that I did not like the look of the bit of new map I saw any more than the original “Wellington of Arabia” offering.

Aspects of command in La Bataille today cover everything that the SPI games do, and then an awful lot more – although to stress the point again, it has reached that point by stages over many years. And what evolution has occurred, it must be said, has not exactly followed a straight path. There is a fork in that path, where you either stay with the evolved basic rules to the system, or head off down the “Regulations of the Year XXII,” which is a posh way of saying that there is another set of rules, advanced rules at that, out there if you wish to avail yourself of them. I did in the past, because I was having a serious struggle trying to get my head around the Third Edition rules.

These days, I find the rules presented in the latest Quatre Bras or Moskawa as quite enough thank you; though why some things are in one set of rules and not the other is still a mystery. Cavalry leaders of special ability is one such rule – it is in the Year XXII rules set, but is absent from what comes as standard in a game such as Les Quatre Bras. Frankly, I regard such leaders and such colour as so integral to the Napoleonic battlefield they should be in the standard rules. And if a game includes a leader who acted like an utter berk, I do not want to have to buy another book to find out why.

Où est D’Erlon?

There are a couple of bloody ironies about the Waterloo campaign. Twice, in the space of a couple of days, Napoleon’s expected reinforcements failed to turn up; and then, on the fateful 18th June, the Coalition armies did to Napoleon what Napoleon had planned to do to them on the 16th – successfully screen one force and envelop and overwhelm another.

To appreciate what happened at Quatre Bras, it is important to understand the details of Napoleon’s campaign strategy, and how it got mucked up.

Essentially, Napoleon’s Armée du Nord was in three component parts as it crossed into Belgium. The left consisted of Ney commanding the I and II army corps; the right was under Grouchy, who had III and IV army corps; and the reserve consisted of VI corps, the Guard and much of the cavalry. The basic premise was that whichever of the Coalition armies shaped for battle first would be engaged by either the left or the right wing, supported by the reserve. The other wing would screen off any contingents from the other Coalition army, and also send a force onto the flank of the main battle to complete the victory. All being well, with this achieved, the rest of the campaign would be a formality.

Of course, wisdom has it that no plan survives contact with the enemy, and in that regard Napoleon was certainly ready to finesse his plan as circumstances presented themselves. But to do this effectively meant getting the right information from his subordinates; and, what is more, having subordinates who could act appropriately as conditions changed. And that is where it started to go wrong. Ney, after an initial reconnaissance of Quatre Bras, told Napoleon he had next to nothing in front of him; and the Emperor took him at his word. Ney might have added, if he were being completely truthful, that he had next to nothing behind him either, as his corps were taking far too long to move up from around Charleroi and Gosselies.

Napoleon, however, was ready to adjust his original plan on the basis of what Ney had actually told him. In that regard, he concluded that Ney had far more men than the situation in front of him required, and so he had Soult write to bring I Corps direct to the engagement presently building at Ligny. But Soult, in the first instance, never told Ney that up to 85,000 Prussians were facing the Emperor, and Ney, for his part, was soon wishing he had not shot his mouth off about how very insignificant were the Allied forces in front of him. There then ensued, through the afternoon and evening of the 16th an absolute farce of order and counter-order, with neither Ney or Napoleon having a decent appreciation of what the other was facing. Ney thought the Emperor was up against a glorified rearguard; and Napoleon still held to the belief that Ney was facing a few bits and pieces, and did not need I Corps.

Jean-Baptiste Drouet, comte d’Erlon (July 29, 1765 – January 25, 1844) was a marshal of France and a soldier in Napoleon’s Army. D’Erlon notably commanded the I Corps of the Armée du Nord at the battle of Waterloo. – Wiki

Who was to blame? I have already blamed Napoleon once for making bad appointments, so one might assume I am going to blame him again. Professional historians might concur, or put the blame more on Ney for the simple fault of failing to think things through. But for me, the blame lies almost entirely with D’Erlon. Whatever vague statements Soult was putting into his communications, or however lost Ney was in the smoke of his own battle, D’Erlon had been in the army long enough to know that doing something was better than acting like a dog chasing its tail. His presence on either battlefield would have been decisive, and as a senior commander, he should have known that, and either quietly told Ney to go stuff himself whilst heading to Ligny…or upset the Emperor just a bit before inviting him to rejoice in a splendid victory achieved by I and II Corps at Quatre Bras. But he did neither.

How does this play in the games? Well, with an air of resignation I must tell you that it does not play in Ney versus Wellington at all. There is no option, no opportunity, to bring D’Erlon to the field. Whether this was a counter sheet thing, or deliberate decision, is hard to say. Then again, although there is plenty of I Corps in La Bataille, it is likely to turn up just in time to see who won or lost, and how dark it has got in the meantime. There is a chance the corps will arrive substantially earlier through the random reinforcement provisions, but this seems bereft of any real historical context. Of course we want games to explore the what-ifs, but to no small extent one might prefer that to be based on what has gone on before game start. The La Bataille game begins at a time when Ney has already told Napoleon of his trifling opposition at Quatre Bras, and Napoleon, in response, has altered his plans accordingly. But if you roll the I corps event on the random reinforcements table (and that is all you do, roll) the corps arrives in Frasnes as if Napoleon or Soult had not bothered to say or write anything at all. Within the historical parameters, it is far more likely that Ney would get the I Corps because D’Erlon dared to turn it around, and would be bringing it on the east edge of the map somewhere between the Bois de la Hutte and the Namur Road.

Paul Comben

End of Part I

In Part II the French cavalry charges, and then, as evening falls, victory is determined.

Read Part II Here

An excellent article, with one ‘rider’. As someone who has just completed mapping QB/Ligny at 100/hex, and who is currently doing the same for Waterloo/Wavre, I have two comments about why those ‘head high’ fields usually are NOT modeled in the game’s graphics and rules.

(1) Withe all the research I’ve done, there is no reason whatsoever (save perhaps the lack of British writers harping on the subject) for anyone to assume that the field at QB was in any way ‘special.’ That is, this whole part of central Belgium grew the same crops, and had the same other agriculture – there’s no reason to think that the fields at QB were in any way different ‘different’ than those around Ligny (several ‘klicks’ to the east) or at Waterloo two days later. Blucher’s Prussians and Napoleon’s main Army were all dealing with the exact same field conditions. Only the British writers chose to harp about them, but

(2) And perhaps more importantly for any game designer, if you try to actually ‘model’ those much described field effects at QB, you run into the same problem as trying to depict, in game terms, the many cornfields and wooden fencelines that were scattered around most ACW battlefields. If you give them any actual game effect, then you also have to be able to show them as being blown/trampled down – a true nightmare in terms of counter clutter and production. And in a Regimental/Battalion scale game, way too far ‘down in the weeds.’

Those crops were certainly all over that part of Belgium, but at Quatre Bras their effect, at least by my interpretation, was a little more pronounced. For Wellington’s forces, coming in hot and tired after force marching in from the north or the west, plunging straight into this stuff or the adjacent woods, directly and without pause into battle, must have been a bit more of an issue. There was no opportunity to get acclimated with the field (what little they could see of it), and to make matters worse, there were other problems in telling friend from foe.I also think of those instances of French Lancers riding up close to Wellington’s forces and thrusting their lances into the ground to give their attacking battalions some sort of marker to aim for.

On the other hand, there’s no doubt that Ligny, quite apart from the villages, had a significant amount of natural and semi natural (hedges, crops etc) clutter, and from my reading, Napoleon’s reconnaissance from the windmill just north of Fleurus did not give him that much of a sight of anything. At Waterloo (and here, I readily admit, I am guessing) the massive and prolonged downpour may have beaten down some of the rye etc, but in addition, the Anglo-Allied army had around 70,000 men, plus cannon and caissons, moving off the roads and into the fields hours before the fight, and this might have brought down a lot of whatever was in the way.

As for how to model the crops in battle at Quatre Bras at least, I don’t think you could do more than broad brush it. I was thinking of a formation change equivalent of the accidental flanking fire Wilderness rule in Bloody Roads South – to apply to anything not in a buildings hex or possibly a road. I’d be tempted to partner that with a limit on checks, say just the first six times one of Wellington’s units attempts to form square with cavalry closing, or when units of different Anglo-Allied nationalities are placed next to each other. Thereafter, it is assumed units have trampled down everything in the way, and units have got used to who is who.

One other thing I want to add is just in what awful state of repair some of the most noted buildings of these fields are in. Hougomont has had to be helped by charity donations before at least parts of it collapse, and the great barn at Quatre Bras, immediately to the north of the crossroads, is a neglected ruin that has been covered with what look like “rave” posters as well as other modern advertising “adornments.”

Considering that these are some of the most important battlefields in European history, and that many a wounded and dying man was placed in these buildings or fought from their walls, I must wonder what that the European Government enclaves just up the road in Brussels think they’re playing at?

The rules have evolved beyond Regs XXII

http://www.labataille.us/rules.shtml

Marshall Ent also has their Premier rules.

Regarding the tall corn: The La Bat. game does have rules governing it catching fire… which tends to happen at the worst possible time.

Regarding the amount of baggage missing from the QB games: What happened to the Artillery Ammunition Wagons that accompany each battery in a La Bat. game (and I might add, lots of people complain about)? We spent a lot of effort including them in the countermix and writing rules for their use. Theoretically each battery thus occupies two hexes… one with the guns and one devoted to this clutter.

Ed Wimble has quite correctly pointed out that I missed the artillery wagon rule used in La Bataille games – whose effect would create precisely the sort of battery clutter I referred to in The Battle for the Crossroads section of Part I. Whoops! Totally my oversight.

In mitigation, artillery wagon rules and their necessary counters, I think I am right in saying, have not featured right through the series, but are a relatively new and very welcome addition. Nevertheless, I don’t think they made it into the recent ATO Vauxchamps game.

Hopefully, Ed or someone linked to the LBdQB could perhaps offer some explanation as to why Rogers artillery battery of Picton’s division got entirely left out of the LBdQB game (I’ve got books, including modern ones, citing the battery commander as to his experiences in the battle), as well as why Vincke’s brigade was placed at the battle instead of Best’s?

I will correct the oversight regarding the artillery wagons in the main body of the text asap.

And now the good news

I have been in communication with my Member of Parliament regarding the terrible disrepair of several key Waterloo campaign buildings – including the Great Barn at Quatre Bras.

In response, today my MP contacted the British Foreign Secretary regarding the upkeep of these sites. I know many gamers will feel that these places need to be properly maintained. The barn has been in an appalling state – not the thing for a place where many brave men sheltered with their wounds or died in great pain.

Regarding Christopher’s comment above, I was really trying to compare the two systems as they appear “out of the box.” – i.e. what you get when you buy either game. I did refer to the XXII rules in passing as they were the only other set I have owned.

With regard to Ed’s comments about rules for the tall crops, I must admit I really wanted to focus on that issue of the French getting all the hesitation and doubt as to what might be lurking in the fields, whereas the not too dissimilar problems it caused for Wellington’s forces were not catered for.

As for fires occurring, I cannot see this, in how the rule is presented, (or how I am reading it!), as being specifically linked to rye catching fire. Just about any hex, by my reading of the rule, can generate a blaze, with exactly the same die roll range. In other words, no type of hex – buildings, woods, “clear”, soggy and boggy bits etc, is more or less prone to catching fire than any other type.

And now for the bad news; I’m pretty sure the battle to save the great barn at Quatre Bras ended last summer after a long and hard fight, and it is slated for demolition in order to enlarge the crossroads itself.

Ed. I’ve just written to my MP again to ask for the current status of these buildings, and what the government of Britain has or has not done to recommend their restoration and upkeep.

If the barn is lost, and I rather think your information is correct, I hope someone in government (Westminster or Brussels) will have to stand up and say something.

As my ancestry is largely Belgian on my father’s side, I have feelings about this from more than one national perspective.

This is where/when that preservation battle was fought:

http://napoleon-monuments.eu/MONUMENTSENPERIL/Quatre-Bras_EN.htm