By Harvey Mossman and Fred Manzo

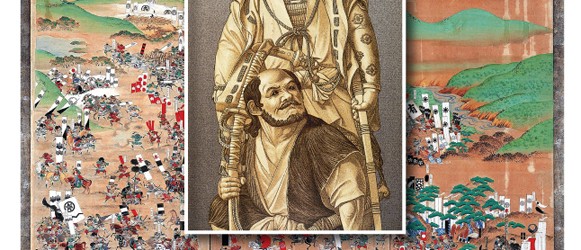

Sekigahara: The Unification of Japan

A while ago we played Matt Calkins’s Sekigahara: The Unification of Japan, a game that won the Charles S. Roberts Award as the best Ancient to Napoleonic Board Wargame of 2011. We used the first edition, although a new printing is now available that has a few minor changes.

Sekigahara is a 2-player game depicting the war between Tokugawa Ieyasu, the most powerful daimyo (leader) in Japan and Ishida Mitsunari, champion of a warlord’s child heir. The 7 week campaign unfolded in 1600 as each leader rushed to assemble a coalition of daimyos to prosecute the war.

The decisive battle occurred at a crossroads called Sekigahara, where disloyalty and defections turned the tide of battle from Ishida to Tokugawa.

Basically, we are dealing with a block game with each block representing approximately 5,000 warriors and the 7 turns each representing one week of real time.

The map of Honshu is both beautiful and mounted. Roads are depicted between various cities and certain areas include resource centers or castles. Edo and Kyoto are particularly important as the players’ capitals. The player controlling the most castles gets extra reinforcements and victory points are received for controlling resource areas. Various recruitment and reinforcement boxes are depicted on the map as well as the game turn sequence and the Impact track, which has to do with combat resolution.

Each rectangular block has 1 to 4 clan symbols (representing its strength) as well as a set up position. Some blocks have gun or cavalry symbols indicating special units attached to their usual complement of warriors.

The cards have corresponding daimyo symbols, the daimyo’s name, and an initiative bid number (more on that later). Some cards also contain a sword symbol which allows that card to activate special units. All of the components are top-notch including black and gold resource cubes to mark controlled areas and the felt bags from which reinforcing units are randomly picked. So, we are talking about another high quality GMT game that requires a serious look.

A typical turn starts with the reinforcement step where players see if they are due any reinforcements, then randomly draw the units from the provided felt bags. These units usually appear in recruitment boxes to be later transferred onto the map by a Mustering action.

Players then decide the turn order by an initiative bid. Each player plays a card face down and, when revealed, the highest initiative number on the card decides who will go first. This can be a painful choice if you want to move first but don’t want to expend an important card to win the Initiative. The turns are divided into A and B steps so essentially there are 2 movement and combat phases.

To move his units a player discards from 0 to 2 cards. If he decides to discard nothing he may activate one stack for movement or perform a Mustering action to bring on reinforcements. Furthermore, one discard allows 3 stacks to move or one mustering action in lieu of movement. Two discards allows every stack to move as well as a Mustering action. In general, units move one point along a road but they can move an additional point if they have leadership (i.e., they have a leader with them or start a move from a friendly castle or capital) or they move solely along a highway or they force march, which requires the expenditure of another card. Players can move 4 blocks without any negative modifiers to their movement allowance, however for every additional multiple of 4 blocks, the movement allowance of the entire stack is reduced by one. This subtle mechanic wonderfully represents the difficulty coordinating the movement of large armies over long distances and players will find it necessary to have positive movement modifiers if they want to maneuver big armies.

Combat may occur when friendly units enter enemy occupied territories. In general, players start a battle by alternatively feeding forces in until one side runs out of units or the cards needed to motivate them, at which point the weaker side flees.

Essentially, in battle, players are trying to accrue more Impact than their opponent. Here is where the cards and the units present in battle create quite a conundrum.

In order to deploy a unit for battle, there has to be a matching clan symbol on the card used to deploy the block. The base impact is equal to its strength as depicted by the number of clan symbols on the block. As you deploy subsequent blocks, you obtain one additional impact per block deployed of the same clan, above and beyond its strength. So if your first block was a combat strength of 3 and you were next able to deploy a 2 strength block of the same clan, you would actually gain another 3 impact (2 for the strength of the block followed by an additional 1 for deploying another block of the same clan). Our take is that units aren’t automatically in a fight just because they find themselves on the same battlefield as their enemy and they don’t automatically generate a consistent punch just because of their size. First, they need to be motivated, and then they need to be committed.

Game Resources