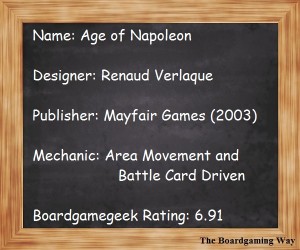

Age of Napoleon

Review, Reflections and Analysis by Paul Comben

When it comes to recreations of the entirety of the Napoleonic Wars, the world of board wargaming has an interesting mix on offer. Games on the subject have come in just about all shapes and sizes, and have presented this very inviting subject with a variety of systems, ranging from the complex and intricate through to designs that have put at least some form of emphasis on shorter playing times and general accessibility.

For someone like myself, who loves the subject but is strapped both for space and game-playing time, a number of most impressive designs have had to pass me by – or at least sit on the shelf at home whilst I wait for life’s fickle wheel to turn again. In the meantime, however, suiting my Napoleonic need in at least some ways, is the card-driven game, Age of Napoleon.

When I look at this game on BGG, I am inclined to think that there are generally two reasons why a design gets a lot of forum posts – in the case of AoN, page after page of them. The game can be amazingly good and incredibly popular, or it can have some issues people are trying to deal with. In the case of AoN, I think the game sits somewhere between those two worlds – i.e. the design does indeed have its enthusiasts (like me) because it has some real merit; but it also has its issues, which not a few players have been willing to work hard to address.

Yes, I like AoN. In fact, I like it a lot. What it has as positives outweigh the range of puzzles and conundrums its system has presented me with. It is a lovely looking game, with a real sense (within the scope of a lighter overall treatment) of the war and the period, and this done with a very modest game footprint and not an exorbitant amount of playing time for a full campaign. Of course, the perception seems to be that it is nowhere near as detailed as some other designs on the same subject, but I think it is detailed enough where it needs to be, and some parts of it are really rather clever.

But let us get the issues out of the way first. Perhaps someone proficient in how people process information could explain precisely why this has occurred, but I think I am not the only person, who, in encountering the relatively short set of rules to this game, inadvertently stumbled over large parts of them. Despite several readings, I missed certain game functions repeatedly, and found it difficult to get a clear picture in my mind as to what some other functions really meant “in the round.” One example of that was getting a clear understanding of the fundamental game differences between a French Ally and a French Dominion; another was grasping how and when I could restore spent forces. Whatever else, you do need to get a grasp on how the various diplomatic alignments, from neutral to belligerent, work in practice, as this is integral to sound play. As for the broader scope of the rules, it may be the order that they are presented in; it may also be that at least a few rules and some of the event cards could have done with an extra clarifying sentence or two. But none of this could be called fatal, and in addition to the considerable help around BGG, most issues can be fixed by the simple expedient of employing a bit of reasonable interpretation.

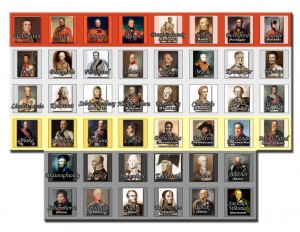

When it comes to the essence of the game itself, working through the component parts of the sequence of play will tell you a fair amount about what to expect from the design. And for the bulk of this review, that is the approach I will take. But just before that, I would like to take a look at the representation of force in the game, and also at the presentation of terrain. In AoN, military power resides with named leader counters, which represent both the command abilities of that individual and the troops he has with him. In the rules, average troop strength per counter is given at about 40,000 men – so we are dealing with units somewhat larger than most Napoleonic corps, and hovering around the definition of being a small army in themselves. However, given the way the game works, you really do not want to go round fighting battles with just one of these units present – more on that later.

When it comes to the essence of the game itself, working through the component parts of the sequence of play will tell you a fair amount about what to expect from the design. And for the bulk of this review, that is the approach I will take. But just before that, I would like to take a look at the representation of force in the game, and also at the presentation of terrain. In AoN, military power resides with named leader counters, which represent both the command abilities of that individual and the troops he has with him. In the rules, average troop strength per counter is given at about 40,000 men – so we are dealing with units somewhat larger than most Napoleonic corps, and hovering around the definition of being a small army in themselves. However, given the way the game works, you really do not want to go round fighting battles with just one of these units present – more on that later.

To my eye, the units are gorgeous, and suit the area map very well. They are colour coded for nationality, and the colours chosen are the ones we have largely learnt to expect in the Napoleonic world – blue for French, white for Austrians, green for Russians etc. The units all possess three numerical values, alongside the pleasing representation of typical national infantry types, and the name of the leader in question. These values are a battle rating, a movement rating, and a seniority rating – the flip side of units shows a “Spent” status, with ratings other than Seniority reduced. The Seniority Rating is largely to do with who can command what; but unlike some games, you can command an army with whomever you choose, as the seniority rating merely refers to how many units that historical personage can lead to triumph or disaster. Of course, it is hard to think of any reason why you would subordinate Napoleon or Davout to some sad twit in a funny hat, but there are subtler situations within the game, where you might only get the overall force you want if you go with a commander who has a less than ideal rating in one area, but has the right qualities in another – note: some of the best fighting generals in the game simply cannot command that many forces.

Artillery and cavalry are not directly present in the system – they are assumed to be within those 40,000-strong counters, and their effects are built into the cards you will use to refine actions and sway battles. Massed artillery (Grand Battery card) is only available to Napoleon, and then only to nationalities beyond the French who had that sort of field artillery capability and are allied to France in a battle where Boney is present. Likewise, only the British can make use of the Reverse Slope card, and the implied cavalry only really makes an impact if you have the Cavalry Charge card or Pursuit card, which denote something big and brutal either by way of a mounted riposte or rout inducer.

When it comes to sea power, Britannia very much rules the waves, and there is nothing anyone else can or dare do about it. The full campaign game begins just about the time Bonaparte’s fleet is being hauled away full of holes or is tumbling down to the ocean floor following Trafalgar, and from that point it is usually only a matter of when (by dint of playing the Britannia card or by Britain being the only French enemy still in the war) until the Royal Navy starts looking for places where it can land troops and cause problems. There are no naval units as such, just Britain’s vast naval capability to move her own forces or those of allies to most coastal spaces around the map – and if Napoleon only wanted control of the English Channel for a day, just imagine what you can get up to when you have control of anything salty and sea-like for up to ten years.

Now to the depiction of the war itself…

Alongside the accounts of the campaigns and battles, the story of the Napoleonic Wars is also very much one of diplomatic stratagems and shifts involving some of the most skilled, notorious, mendacious and utterly untrustworthy figures in European history. Former enemies became allies, and then became enemies again; eternal friendships were avowed to, and then blown away when other money talked or the wrong noble couple ended up marrying for reasons that had about as much to do with mutual attraction as Caesar had with the knives in his back.

In AoN, the Diplomatic Phase comes at the very beginning of the campaign year, but the rub is that you will only be able to use whatever dedicated diplomatic cards you have left from the hand you played through the previous year. New hands come later in the present year’s sequence, which, of course, should make you loathe to play strong diplomacy cards simply for their subordinate purpose of shifting armies about. One thing you will find with AoN is that the game is rather more stringent in the use or misuse of cards than many other card-driven designs – or at least, that is my perception. With AoN, it is not merely a matter of trying to acquire and employ the best cards, it is the challenge of having any cards left for those key phases tagged on to the aftermath of movement and battle.

There is a clear tension here, as in most cases, armies can only move by spending cards; but when opportunities arise to pull the diplomatic rug from under all those shiny buckled shoes, you might regret not holding onto that prized card rather than sauntering towards another heroic engagement. When you look through the game’s Diplomacy Phase cards, they tend to reflect two particular trends – attempts by the Napoleonic “regime” to impose its order and its preference in alliances on the greater and lesser powers of Europe; and in opposition to that, the efforts of Britain and whoever else is around to undermine every French move in that context. Where the game gets particularly subtle is in the Coalition ability to use cards, that, on the face of it, are about extending French power, but in reality, are setting up France and Napoleon for a serious fall. Some of Napoleon’s actual ham-fisted attempts to establish his line around the royal houses of Europe are very much part of this, but such Coalition play can also reflect the simple resentment of people who feel they are being taken advantage of. To that end, the game world’s Coalition, and sometimes just Britain as the one constant enemy, will often want the French to have more power and more dominion, because sooner or later it will lead to serious problems.

There is a clear tension here, as in most cases, armies can only move by spending cards; but when opportunities arise to pull the diplomatic rug from under all those shiny buckled shoes, you might regret not holding onto that prized card rather than sauntering towards another heroic engagement. When you look through the game’s Diplomacy Phase cards, they tend to reflect two particular trends – attempts by the Napoleonic “regime” to impose its order and its preference in alliances on the greater and lesser powers of Europe; and in opposition to that, the efforts of Britain and whoever else is around to undermine every French move in that context. Where the game gets particularly subtle is in the Coalition ability to use cards, that, on the face of it, are about extending French power, but in reality, are setting up France and Napoleon for a serious fall. Some of Napoleon’s actual ham-fisted attempts to establish his line around the royal houses of Europe are very much part of this, but such Coalition play can also reflect the simple resentment of people who feel they are being taken advantage of. To that end, the game world’s Coalition, and sometimes just Britain as the one constant enemy, will often want the French to have more power and more dominion, because sooner or later it will lead to serious problems.

As for the French, they are not without some strong diplomatic play when the right cards are in their hand. In particular, they can “damp down” Europe with a range of neutrality/alliance/dominion moves. These often include being able, as was the case historically, to have Russia onside and much else of Europe kept quiescent through the imposition of dominion status. This is all well and good, but if the timing is not perfect when it comes to reaching for those relevant victory conditions, (and it very rarely will be perfect), you can look forward to much of your Napoleonic edifice falling into periods of disrepair and revolt. In short, the game provides far too many causes of disruption to expect greater France to endure without serious hassle. Putting a major power into dominion status is likely to be a short term fix, as the British will put that power into insurrection the first chance it gets; and once that is done, the French will potentially be looking at trouble for the rest of the game.

Ultimately, the big difference between the two side’s diplomatic moves is that Coalition efforts are about stoking things up, and those of the French about keeping things under control. But here the game is clever again, because the “higher” victory conditions for the French, in terms of control and conquests, include stipulations that require entering territory you might rather keep out of – and Russia is the prime example of that. As the French, you cannot win big unless you have trailed the tricolor around a lot of Eastern Europe’s forests, plains and steppes, which hardly sits well with dynastic marriages and concords made on the Tilsit.

Diplomacy is followed the Insurrection Phase. Clearly these two phases go hand in glove, with the anti-Bonapartists looking to capitalize on whatever prospects present themselves. To commence an insurrection against French rule, the opposing player must play a card that prompts such an uprising. That might involve a fair amount of prior diplomatic skullduggery, and as Spain provided one of the best historical examples of insurrection against the French, we can use that case to illustrate the actual gameplay involved in creating the same effect. In 1805, Spain in the game, as Spain was historically, is a French ally. If you are playing as France, Spain as an ally is, of course, entirely acceptable, as that fits in with victory conditions. But then the indomitable British, with not a great deal else to do with their cards for want of continental allies, go and play some piece of diplomatic bad news most likely linked to French imperial dynastic pretentions (the Reign in Spain), and this then turns Spain into a French dominion – i.e. being bullied and told what to do. That, in itself, is not too much of an issue, as on the surface, Spain is still in the fold and behaving itself. But now, Spain is only one step away from an uprising, and of course, as then actually happened, Spain blows up, (Perfidious Albion and its shopkeepers play that Insurrection card) and now the Spanish army is mobilizing and a British expeditionary force is on the way. Bother!

For the French, insurrections need not be the end of the world, as not every country that might revolt is going to have that much of an army, or be in some vitally important position on the map. But it is all wear and tear on French resources, and as the game progresses, and that French army is not quite what it was, having a major country in revolt on one side of the map whilst Napoleon is berating his marshals on the other side, is not an ideal situation.

The next phase is the Strategy Phase, where unused cards are returned, a new deck formed if necessary, and a variable number of cards distributed to the players dependent on the current war situation. The most important aspect of this phase is how a failing war effort and a deteriorating overall situation is going to get worse as your hand size declines. You will find yourself unable to move or reform many of your forces, and perhaps those better cards in your hand might have to be used simply to get some kind of army from A to B. I am tempted to say that one thing the game is missing here is a reward/penalty for a major battle won or lost, which is something we do see in a range of other 18th/19th Century themed designs. Yes, you can see your reward or loss in the pure casualties and the spent formations, but the aura of victory and the pall of defeat are things which go beyond that, and I cannot help thinking that being immediately able to draw (or in defeat lose) another card might offer that bit of something extra.

Hand management is very important in this design. I have played many card driven wargames, and hand management has been important in all of them; but in this one, because of the demands on a player’s resources beyond moving armies and improving the odds, cards seem to fly out of your possession at an alarming rate, and given that some card opportunities for your present hand do not occur until the next turn, the dilemmas of “play or pass” are that much heightened. And rest assured, smaller hand sizes will cripple your efforts, and even with larger sizes, you still need to think carefully about what you aim to do.

When it comes to the Reinforcement Phase, players are faced with some other fundamental aspects of the powers’ ability to wage war. All the major powers have a force pool (called a “Reserve” in the game), but while some nations have a formidable array of units, there is often a lot of mediocre tosh in the mix. A great deal of what Austria, and even more so Prussia, can initially put in the field is distinctly underwhelming. Reflecting outmoded doctrine and geriatric leadership, the force pools for both these powers do not improve until they have been forced to surrender – and the French cannot really go gamey and avoid trampling these nations into a better state of military practice, because you need those conquests to win. However, whilst the game caters for the improving nature of those central European armies after the historical reforms conducted by Radetzky (Austria) and Stein (Prussia), I have yet to play a game where the right cards turned up to initiate the process. In fact, I am tempted to think that fundamentals like this should not rely on the right card getting into the right hand, but should have their somewhat random entry produced by die roll once the qualifying surrender has occurred. This might prevent a key event becoming a non-event, or for key events to fall out of any timing (i.e. they happen too far away from their historical moment or context) with what was supposed to cause them. For me, when I first read through the rulebook to this game, I thought that some fundamental events were a bit too elusive (i.e. if your country has been militarily smashed, there should surely be a sense of urgency to reforms that seems missing from the game).

But whatever I think of the evolution of forces, the game is still interesting in terms of how armies are deployed and enlarged. Nations each have a mobilization and deployment limit – the first reflecting the size of forces that nation can keep in the field, and the second the number of Reserve units that can be brought onto the map in any given Reinforcement Phase. Taken together, these two conditions keep force levels at realistic levels, and neatly reflect the profile of different nations’ military ethos and capacities. The French can sustain the largest overall field strength, with up to ten units on the map at any time, plus a small contribution from their allies. The Russians come in next, with a mobilization limit of eight and a limit of four on deployment. The Austrians and Prussians can offer more than their original middling quotas after (or if) they get their reforms, but coming in resoundingly last are the British, who can never put more than two homegrown corps into the field at any time. What this means is that Wellington (the best commander out there after Nappy) is likely to become the Hannibal of this war, leading various polyglot assemblages of strength to wherever he can do the French cause the most harm. There is nothing wrong with this, of course, given all those Spanish and Portuguese troops he led in Iberia, but it can take a bit of getting used to, to see Old Nosey ducking round the Tyrol or crossing the Rhineland with a stack of Austrians and Prussians/Russians (or both!) in tow.

One thing that gameplay experience has taught me to be careful of (certainly when playing the full war scenario) is cherry picking all the best forces for each country ahead of the makeweights. As the French, for example, it is obviously tempting to get those renowned names with their superior campaign values onto the map as soon as possible, but as the game’s combat eliminations are determined by the owning player in nearly all cases, you really need to do yourself a favour and add some cannon fodder to give you an option beyond having the likes of Davout or Suchet having to join the casualty pile. The same also applies to satisfying attrition losses – it might seem gamey, but within the context of the game as is, it is all very well marching around with a stack of martial superstars, but when attrition inevitably kicks in, one or two of those best baton wielders are going to be out of the game – perhaps for good. And beyond all that there is consideration of the later periods of the game – whether you are reaching for victory in 1813 or trying to stave off defeat, it will be a help if there is still something of value to put on the map other than the too old, too young, or too inept.

Finally, the Reinforcement Phase is where you can restore Spent (flipped) forces to their fresh side, at the cost of one card per area where any force is spent. Spent forces are in a very precarious position – not so much because their moving and fighting values are somewhat reduced, but because any further hurt will permanently remove them from the game, and that will do no good to your cause at all. The problem is, that sort of restoration is going to have you spending cards from your new hand before you have marched anywhere, but nevertheless, unless you have some mitigating factor, restoring forces really should be a priority.

We now come to the Campaign Phase, where the actual marching and fighting is going to take place. AoN is played in yearly turns, whose centerpiece is the up to six Campaign Rounds. The last two of these rounds are deemed winter, and unless you have a very good reason to be moving, you really should be keeping still and waiting to play whatever diplomatic bombshell you have left in your hand.

In any round, generally one side (usually the French first in the earlier period of the war) will activate one army (stack) by spending a card without using its event, and this is followed with an activation by the other player. You can opt to pass if you want to (or have to), and frankly, hand management is so important in the game, and attrition so potentially harmful, that you really should not go moving stuff around unless you have a clear idea why.

March attrition (usually affecting forces marching three or more areas, or any distance in winter), naturally affects bigger assemblages of force more than smaller packages, so pure shifts of position might be better done by smaller contingents activated separately – albeit at the cost of spending more cards for entire movement. On the other hand, if you are going to engage in battle as the attacker, you will have no choice but to shift at once with everything you have got (unless you have a Major Campaign card, giving you multiple movements), so very much part of the consideration of entering combat is how you are going to arrive on the field. The French have certain advantages here, in that their “corps” are often that bit more mobile than their adversaries (an extra movement factor) and can therefore close over longer distances. But that sort of move can easily flip a number of corps to their spent side before they have done anything, and as I said a little earlier, spent units will end up in the permanently destroyed pool if any further hurt comes their way.

Within the wisdom of diverse cultures, there is the teaching that travelling a-ways to a fight is something to be done by your opponent…and here and there is also advice about “living to fight another day.” What this means in the context of AoN should be readily apparent after you have played a few games. Most significantly, the game gives a significant advantage to the French player if they have worked out how best to employ it. Rather than using the better French movement allowances to trek deep into the back of beyond, these same allowances will often permit their forces to intercept adjacent, moving Coalition hosts (at the cost of spending a card but with no attrition risk) or avoid interception themselves. There is a lot to be said for sitting in the right spot and seeing how well, or badly, the Coalition can shift things in your direction. And while no maxim is an absolute, even if there is a big enemy force mustering, it might not be so big when it finally arrives, and via withdrawal your niftier French might well be able to skip out of the way leaving the foe gasping and grasping at nothing.

As for battle, that is a relatively straightforward business, and one where you should really look to have as much as possible in your favour if you are going to get a decisive result. Having said that, the actual battle process here is not one of finesse – more bring on those “big battalions” and have at least one combat related card to hand. At first sight, the battle results might not seem particularly bloody or telling, but the woe of losing anything like a big battle is rather pronounced. Alongside those forces permanently erased or temporarily lost as prisoners, the loser automatically incurs an extra hit for having lost, and unlike the victor, cannot restore his entirely spent army by playing a card. In fact, all sorts of baneful game mechanisms can kick in after a defeat – you may well want to shift your spent remnants far away from the source of harm…but then you risk further attrition to your frail forces, and if it is winter, and you just happen to end up in one of the less hospitable portions of the map (there’s no “feast in the east” for a start), you can readily go from having some army to some sad recollection of one you have not got any more.

Needless to say, the trick is not to lose the battle in the first place – combat cards can help you there, but be certain they can up your effectiveness on the results table before laying them down. There is no point in putting down cards that increase your strength, but not to the point where you shift up to a higher strength range on the table. Furthermore, you should be just a bit wary of sending your massive host against what gives every appearance of being a stack full of indifferent factors. Even large differences in combat strengths are no absolute guarantee of inflicting more casualties than you receive, or actually being determined as winning the fight – you probably will win, but it is not certain, and the game does provide a sort of narrow margin victory, which can hurt rather more than it pleases. Beyond that, your intended heap of weak victims can acquire more teeth if they are fighting on home soil (each of their corps gets a +1 to their strength), and if they also have a fog of war card, all those tasty modifier cards you were planning to use will be as much good as wrapping paper without a present to put it round.

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington by Robert Home – wearing his major generals uniform in 1804

Beyond these issues, it is worth repeating that the best leaders/units in the game need protection from deadly turns of fortune – although there is a “Hero’s Death” card which will rob you of your best leader even if he is hiding behind plenty of other men. I think there are very sound design reasons for the battle system being as direct as it is (not a game you want to slow or clog up), but I am tempted to suggest a bit more finessing might not have gone amiss – that Wellington, when in company of at least one other British unit, should always get the Reverse Slope benefit; that Napoleon, when leading an army of at least three units from 1809 onwards should always have The Grand Battery benefit etc. What I am glad is not present is any form of tactical matrix – all that random selection of refused flanks, reconnaissance in force, withdrawals, bombardment etc. I do not feel particularly comfortable saying that, as I seem to have purchased an awful lot of games where this stuff is present…but I do not like it. Tactics are meant to be about commander quality, the abilities of armies, the nature of the field etc., so to have some military rock/scissors/paper exercise going on has never been among my favourite mechanisms for resolving or finessing combat.

The last thing to say about operations on the map pertains to its geography. Outside of western and central Europe, the map becomes hostile, especially during the winter rounds. Many areas in the east and in Iberia are in a slightly difference typeface, to denote the fact that they are barren. There are also mountain and swamp areas, and where the misery really kicks in is when you foolishly, or perhaps unavoidably, make a long march in winter through harsh terrain (Tolstoy anyone?), which will cut an army (most likely spent) to pieces. If you get this sort of thing wrong, your pride and joy of an army can disappear between the last marches of the year and the specific winter attritional rules at the end of the turn. That is the time to be in small stacks in home or capital areas, which is a nice modeling of what armies did in practice.

Also towards the end of the turn is a Surrender Phase, and a Victory check. Forcing the surrender of a major power revolves largely around what force it has left in home areas and who controls its capital. Britain, however, is untouchable. And this being altogether a very different age of war, defeat and surrender can be followed by all kinds of diplomatic volte-face, with nations turning this way and that…until they are likely back in the same modes of belligerency they started off in. Victory levels for both sides are ranked as either marginal or decisive, and my reading of them is that their particular conditions are rather more demanding of the French. In essence, even at the marginal level, if the French have not got what could just about pass as a European empire of some sort, they are not going to win, full stop. To win big, they must totally dominate Europe. For the Coalition, France left with next to nothing but herself wins a marginal victory for the forces of monarchy and the ancien regime; but if she surrenders, or if Napoleon’s unit is permanently lost, the Coalition wins a decisive victory. So as the French, yet again, keep Boney in plenty of company.

And in case you are wondering, I tend to doubt that a rather ahistorical “Kill Nappy” strategy is going to work that well. Indifferent Coalition armies overreaching across the map to try and pin him down is not the way to do things. Far better, in fact, to let the heat and the cold, the drought and the snow, have a chance of polishing him off, than trying to fight this or that costly big battle with the hope of a fluke result at the end of it.

There is just one more thing I wanted to add, and that regarding Napoleon and the other “personalities” in the game. At Ligny, when Napoleon’s career had only days to run, the word among French commanders was that the Napoleon they had known did not exist any more. However, if you play a full campaign in AoN to its potential full course, Napoleon will be exactly the same in 1815 as he was in 1805. That is not me be overly critical, it is just a reality of the game. Likewise, unless you lose Kutusov in battle, he will still be falling asleep or hugging people in 1815. No commander, in fact, changes, gets worse or gets better, they simply are what they are and nothing else. There is a “Fallen From Favour” card that can shift a presence into the background, for a while at least, but that is not really the same thing as a bit of natural death or an accident.

Staying with this theme, perhaps the oddest card in the game is the “Republicans and Royalists” event. Played by the Coalition, it forces the French player to dispose of Napoleon’s services and replace him with someone taken from the reserve pool. The illustration on the card implies assassination, but the card’s text does not make it clear whether Boney is gone for good or can re-enter later as reinforcement. It is tempting to say that his goose has been well and truly cooked, but in the normal run of things, that is meant to lose the French player the game. And frankly, if the game does want to present a successful royalist coup, I fail to see what an enduring war would be about, as the restoration of the French monarchy was precisely what the crowned heads of Europe were after. Frankly, at least for me, this is a bit of a rogue card, and if there is an answer on BGG, and there might well be, somewhere, I have not tracked it down.

But really, what does it matter? If your Napoleon comes back having survived his injuries, fine. If French royalists want to pursue more war for their own reasons, fine again. You are working with history your own way after all, and that is the purpose of playing the game and enjoying it. What you have at the end of the day is enough colour and fun to take your mind off the occasional hiccup – the fundamentals of what you might want in a game of the Napoleonic Wars is present – armies clash, freeze, starve and waste away; alliances come and go; Napoleon marches into Russia or races around his own borders when the tide has truly turned; and frankly, you can have a very good time building up powers or breaking them up. Perhaps it could have been better here and there, but it is still better than you might think. If you get a chance to play this, my advice is to give it a serious go.

Paul Comben

Game Resources:

AoN v2 main rules (published version).pdf (Give it plenty of time to load)

AoN v2 main rules (published version).pdf (Give it plenty of time to load)

General rules explained by game concept

Major Power Diplomatic Alignment Chart

Paul,

Thanks for the thorough (and positive!) review. A few clarifications, if I may:

“I am not the only person, who, in encountering the relatively short set of rules to this game, inadvertently stumbled over large parts of them”

Indeed, and the why puzzles me, but so it goes. Perhaps it is because I don’t repeat myself much and there is also little fluff in the rulebook. Pretty much everything matters.

“the seniority rating merely refers to how many units that historical personage can lead to triumph or disaster. Of course, it is hard to think of any reason why you would subordinate Napoleon or Davout to some sad twit in a funny hat”

To be clear Napoleon cannot be subordinated to anyone as he has the highest seniority rating. More generally, a commander can only be subordinated to another commander with an equal or greater seniority rating.

“Massed artillery (Grand Battery card) is only available to Napoleon, and then only to nationalities beyond the French who had that sort of field artillery capability and are allied to France in a battle where Boney is present.”

Not quite true. Napoleon’s presence is only required to use this card when attacking, not when defending. Look for the semi-column in the card text; it clearly (?) makes the requirement that Napoleon be present only applicable to attacking.

“However, whilst the game caters for the improving nature of those central European armies after the historical reforms conducted by Radetzky (Austria) and Stein (Prussia), I have yet to play a game where the right cards turned up to initiate the process. In fact, I am tempted to think that fundamentals like this should not rely on the right card getting into the right hand, but should have their somewhat random entry produced by die roll once the qualifying surrender has occurred.”

A fair concern that I sought to attenuate in the second edition (published by Mayfair). See Rule 2.3.12. My cardless version makes these events automatic based on certain requirements.

“I am tempted to say that one thing the game is missing here is a reward/penalty for a major battle won or lost, which is something we do see in a range of other 18th/19th Century themed designs. Yes, you can see your reward or loss in the pure casualties and the spent formations, but the aura of victory and the pall of defeat are things which go beyond that, and I cannot help thinking that being immediately able to draw (or in defeat lose) another card might offer that bit of something extra.”

An interesting idea.

“In any round, generally one side (usually the French first in the earlier period of the war) will activate one army (stack) by spending a card without using its event”

Except for the first move of the campaign phase.

“spent units will end up in the permanently destroyed pool if any further hurt comes their way.” Spent corps do not get any more permanently destroyed than fresh corps. They’re just weaker. Whether a loss is temporary (corps returned to the reserve after some time in the prisoners’ box) or permanent (corps not to return unless the Veterans card) is played is not affected by whether a corps is fresh or spent.

“Staying with this theme, perhaps the oddest card in the game is the “Republicans and Royalists” event. Played by the Coalition, it forces the French player to dispose of Napoleon’s services and replace him with someone taken from the reserve pool. The illustration on the card implies assassination, but the card’s text does not make it clear whether Boney is gone for good or can re-enter later as reinforcement. It is tempting to say that his goose has been well and truly cooked, but in the normal run of things, that is meant to lose the French player the game. And frankly, if the game does want to present a successful royalist coup, I fail to see what an enduring war would be about, as the restoration of the French monarchy was precisely what the crowned heads of Europe were after. Frankly, at least for me, this is a bit of a rogue card, and if there is an answer on BGG, and there might well be, somewhere, I have not tracked it down.”

I guess that’s because it does not seem like people have been confused by the card. The illustration relates to an actual, but failed, attempt against Bonaparte in 1800. That said, the card is just about Napoleon having to go home to deal with domestic political issues. His corps is substituted and returned to the reserve, which means he can therefore return in the reinforcement phase (assuming there is no issue with the mobilization or deployment limits).

Cheers,

Renaud

Hello Renaud

Many thanks for giving my article a nice reception. I had the game set up for much of the last few weeks, whilst my wife was away on a respite health break much needed by us both. Although I put it away a few times after finishing, I could never resist having another go shortly afterwards.

I must also thank you for the clarifications. As I went from the playing to the writing, I did wonder what was really behind so many rules questions, but apart from adding the occasional extra sentence here or there, all I could think of was that the game’s pretty fast pace has players reacting faster than they are thinking (this is all conjecture!) and so they “speed” past things that might otherwise have picked up. Certainly, one or two of my own slips seem to be due to that.

The only other thing I would say about the rules as they are goes back to that Republicans and Royalists card – I had another look at it, and think I might have got the implementation right if I had not had an embarrassing hole in my personal historical recollections concerning attempts to kill Bonaparte. Having said that,please forgive me if I still think the card is short of clarity when it comes to where Napoleon goes after he has been replaced. But hey, now I’ve got some definitive designer clarifications, so all is well!

There were two other thoughts I had about the game’s functions, but left them out of the piece to avoid any sense that I was somehow twisting your design out of shape. One, which I’m sure plenty of other people have thought of (possibly) is to blind draw your arriving forces; the other connected with doing something with the occasional unit here and there that can get left “hanging out to dry” as you run out of cards to shift them with. I thought of being able to declare them as withdrawing into a fortress (like a lot of Napoleon’s forces historically in 1813) and giving them immunity from any one hit result…or something like that. I might give it a try, as I can take a token from anywhere to show that the force in question has gone behind the walls and the works.

Before I end, there is a good chance I will be covering some aspects of The Price of Freedom in the not too distant future – it will not be a dedicated one game piece like this, as I have an article in mind looking at how a range of ACW games cover the depiction and usage of the same prominent leaders.

All that remains is to thank you again for a design I enjoyed tremendously, and was, in a real sense, just what the doctor ordered.

Very best wishes

Paul