By Paul Comben

Medieval Cavalry in Board Wargames

According to more texts than I would care to count up, the Battle of Hastings lasted from the morning of a mid-October day in 1066 to the coming of the dusk. The Saxons stood bravely, the Normans charged up Senlac Hill (nope!) ferociously, and in the aftermath of that bloody occasion, the battlefield got shifted erroneously – a little more on that in a moment. Near three hundred years later, at Crecy, another English army stood on another hill (the right one), filled it full of holes, and concluded the ensuing and rather larger battle than Hastings in a fraction of the time. But of course, Agincourt takes the biscuit, for there, a socking great big French host, all banners, boasts and breastplates, faced a small and hill-less English host in a very bad mood because of guts ache and the weather, and was wrecked in less time than it takes to go a few stops on the average London bus route.

The story of medieval arms and practices (or of the immense ancient era, for that matter) is very much one of particular weapons, tactics, cultural outlooks and so on, having each their periods of ascendancy and each being responded to by a new form of attack, a better form of defense, or plain social and cultural pig-headedness. What is interesting, is that through all the bygone millennia, wherein practically all battlefield weapons did what they did by blades, points or weight (i.e. swish, stab and smash), there should have been so much variation found in how armies went at each other. From the European armies of antiquity to those that just brushed into the gunpowder age, the number of different weapons that swished, stabbed and smashed, the number of different soldier-types who employed them, the formations they were put into, and the tactics that pertained to them, truly boggles the mind.

In 1066, it took William all day, mounted knights notwithstanding, to break a Saxon army that was probably behind rudimentary field works on Crowhurst Hill (my earlier article on The Boardgaming Way deals with this); but had he faced Henry’s or Edward III’s forces, he would have been wrecked in less than an hour and left wishing he had not willingly cancelled his return transport arrangements. On the other hand, the French 1415 army, or the 1346 one, would have gone through Harold’s host, including his ditch and his interwoven twigs, without any real trouble at all – tanks crushing the wire at Cambrai springs to mind as one near-modern comparison; but in the medieval period, it was not so much that entirely new assets were invented, just that those already around were gradually improved – and much of this had to do with the efficacy, and often simply the threat, of the mounted arm, and the various responses to it.

When it comes to gaming the battles of this era, it would have to be said straightaway that this has hardly been major box office over near all the time the hobby has been in existence. I did own and play Yeoman (part of SPI’s PRESTAGS series) back in the 1970s, but with its drab and utterly uninspiring look it was rather akin to trying to appreciate the paintings of Turner or Van Gogh via a series of black and white photographs taken by someone with a very small camera. A few years after Yeoman came Agincourt, also by SPI, which modeled the historical battle so well, you could not get anyone to play the French unless they were sozzled, full of themselves, ready to wage a tenner on winning easily…and had not looked at the combat results table – which is more or less what happened in real life. Nevertheless, the game did have a fair bit of colour, and I liked it – despite my original copy having a counter sheet so out of alignment it could have taken Grognard’s “Name the Game” unit counter quiz to an entirely new level.

When it comes to gaming the battles of this era, it would have to be said straightaway that this has hardly been major box office over near all the time the hobby has been in existence. I did own and play Yeoman (part of SPI’s PRESTAGS series) back in the 1970s, but with its drab and utterly uninspiring look it was rather akin to trying to appreciate the paintings of Turner or Van Gogh via a series of black and white photographs taken by someone with a very small camera. A few years after Yeoman came Agincourt, also by SPI, which modeled the historical battle so well, you could not get anyone to play the French unless they were sozzled, full of themselves, ready to wage a tenner on winning easily…and had not looked at the combat results table – which is more or less what happened in real life. Nevertheless, the game did have a fair bit of colour, and I liked it – despite my original copy having a counter sheet so out of alignment it could have taken Grognard’s “Name the Game” unit counter quiz to an entirely new level.

In more recent years the situation has improved appreciably. Alongside the occasional one-off or stand alone game, like Worthington’s Scotland Rising, there have been several series of titles, including Richard Berg’s Men of Iron (MoI), Ludofolie’s steadily growing Au Fil de L’Epée (AFdE), and going back a few more years, the Clash of Arms pairing of titles, Baron’s War and Wallace’s War. Those last two games were not a rip-roaring success in terms of player appreciation, (in the case of Baron’s War it comes to something when the last BGG posting is about a nasty smell in the box), but initial rules issues aide, these two games, with their four battles, were a serious effort to model combat of the period and thus deserve to be here.

Two other things that need to be said before looking through these designs – first, that I was not overly disposed to include games that are very much on the lighter side of things – whatever their precise remit, they are basically “move cavalry faster than infantry, add up the factors and bash away with the dice.” Secondly, I do have an issue with Hastings games, as there is now a welter of evidence that Senlac Hill had about as much to do with the battle as a shellfish stall on The Old Kent Road had to do with Stalingrad – again, see my article, which introduces some of the main arguments and evidence. I would have loved to include a Hastings game here; but it is more than simply moving from one hill to another. Part of the new argument, which is the product of hard work by dedicated people, is that the Saxons did indeed build effective works across one of the best choke points of the then English coast (which in Sussex and Kent was very different to today’s), and this helps explain why the battle lasted as long as it did. Without those positions, and without the massive Malfosse on the edge of the field (and there is a very broad and very deep ancient ditch at Crowhurst), I have to ask myself what any Hastings title up till now can tell us about the battle and the nature of the armies that fought it? Answer, not very much.

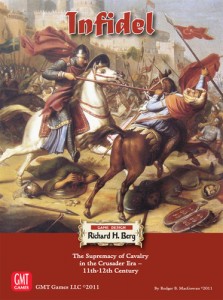

With the games I will be considering, the furthest we can go back is the First Crusade (Richard Berg’s Infidel), and then, after travelling through the subsequent eras via a range of designs, we end with another in the Berg Men of Iron series, Blood and Roses, wherein the armies of the white and the red rose do some very violent things in the snow at Towton, some utterly treacherous things in the lost and found field of Bosworth, and, amongst other brutalities, go hacking around in the pile of mud and manure that was the Fifteenth Century’s take on Saint Alban’s High Street – which is, however, quite genteel now, with roundabouts and bus stops and a Costa’s. Anyway, that is the order I will be looking at things in, from the time when cavalry was the force on the medieval battlefield, to when and why it was not.

It will do no harm by way of introducing all this if we look at why man and horse became an integral aspect of so many wars and battles, for by doing so, we can highlight the principle strengths of cavalry, as well as some of the weaknesses. Horses, as man discovered in the far long ago, could be tamed and trained. In situations of conflict, the horse enabled its rider to move faster than he could all by his shaggy little self. The horse could also carry considerable weight and deliver that full package of weight (horse, man, armour, weapons, as an imposing shock assault into the enemy line). Furthermore, with his added height and swifter mobility, the mounted warrior could scout for the enemy and get out of the way of trouble if he had to. Mobility also meant cavalry could harass an enemy force by niggling at it, bothering its flanks and doing all sorts of nasty stuff to its rear. As a mobile weapons platform, in some circumstances at least, the horse was an asset enabling the rider to deliver attacks with spear and bow without getting into the range of returning harm. Finally, there were few more imposing sights on many a battlefield than seeing a mass of armoured cavalry bearing down on your dubious foot, who might already have been on the point of fleeing before anything bad had actually happened.

It will do no harm by way of introducing all this if we look at why man and horse became an integral aspect of so many wars and battles, for by doing so, we can highlight the principle strengths of cavalry, as well as some of the weaknesses. Horses, as man discovered in the far long ago, could be tamed and trained. In situations of conflict, the horse enabled its rider to move faster than he could all by his shaggy little self. The horse could also carry considerable weight and deliver that full package of weight (horse, man, armour, weapons, as an imposing shock assault into the enemy line). Furthermore, with his added height and swifter mobility, the mounted warrior could scout for the enemy and get out of the way of trouble if he had to. Mobility also meant cavalry could harass an enemy force by niggling at it, bothering its flanks and doing all sorts of nasty stuff to its rear. As a mobile weapons platform, in some circumstances at least, the horse was an asset enabling the rider to deliver attacks with spear and bow without getting into the range of returning harm. Finally, there were few more imposing sights on many a battlefield than seeing a mass of armoured cavalry bearing down on your dubious foot, who might already have been on the point of fleeing before anything bad had actually happened.

On the other hand, a horse and its rider makes a far bigger target, and also multiplies the number of vulnerabilities the “package” is prone to – hurt the horse, one great mass of susceptible flesh, and you harm the rider; kill the horse and the rider is often entirely hors(e) de combat. And while horses are not the dumbest of animals by any means, the battlefield rider (with some exceptions in the European armies, where the horse might well have been more intelligent than its mailed and plated baggage) is going to have to do all the thinking for it, and then much depends on the mount’s willingness to comply – which might not be forthcoming if the beast is panicked by any number of things. Finally, to this day, the owning of horses is often seen as a symbol of social status and wealth, which, in hierarchical societies where the mounted arm was especially prized, could lead to a lack of cohesion within armies (them and us – think of events in the French army at Crecy), and also tie the arm to haughty notions of etiquette and protocol way ahead of the simple practice of good military sense.

But now we travel to the era of the Crusades, and to an area of conflict where the clash of cultures was reflected in contrasting armies and doctrines of engagement. As Infidel’s designer states, the armies of the Eastern powers were the inheritors of military traditions and armaments that went far back into antiquity. Indeed, in the forces that confronted the Crusader armies in the hundred years or so the game covers (First to Third Crusades) there was not a great deal that would have been beyond the ken of Alexander, Trajan, Valerian or Julian – the designer actually uses the example of Crassus, but why linger on the fate of a Roman chump who supposedly ended his days (if you believe the most lurid accounts) with a mouthful of molten moolah?

As a prime example of how concepts endure, what Jackie Fisher would envisage centuries later for his battle cruisers (move fast, hit with a long reach and not get hit back) was essentially how the Crusader’s enemies composed their armies – mobility and massive amounts of missile fire. This was all fine and dandy whilst the armies of the Middle East were facing other armies of the Middle East, but against heavily armoured knights the effectiveness of the eastern bow could be open to question. And of course, it was much the same with those battle cruisers – “float like a butterfly and sting like a bee”….butterflies are fragile and have a depressingly short life, while bees can tear themselves apart in seeking to deliver their sting.

In Infidel, the character of those Middle Eastern armies is displayed through a multiplicity of force types, though any player is soon going to notice that the first recourse of any such host is the mounted archer. Such armies are certainly not bereft of heavy cavalry; but there are important differences compared to the European heavies. The European knight can be the Muslim player’s worst enemy, or its own worst enemy – superb melee weaponry, superior armour, well-trained mounts and codes of honour ignited to a blazing obligation by being in the “Holy Land,” are likely to have any mix of volatile effects on just how they comport themselves on the battlefield. A law unto themselves is the most apt way to put it.

So how is all this reflected in the game? In a nutshell, this is not a game (or a series for that matter) where the dogmas, cultural mindsets and practices of medieval conflict are reflected in a mass of “shalts” and “shalt nots.” Appropriate units can charge (or countercharge), with commensurate benefits and restrictions according to era. There is also a combat matrix (the sort of thing well known to players of GBoH – Great Battles of History) that reflects where advantage will lay in any melee between different unit types. But it is up to the player to devise how to translate all of this into effective tactics. If we stick with the horse archers, the rules do not tell you, let alone actually insist, that you twang the old bows mid-move and then turn away from harm – it is simply there, staring you in the face.

What is key in the multi-era MoI system is that the subtle aspects of military evolution over this entire period are often relayed by the combat-related modifiers on a game-specific set of tables – that is, at least some of the modifiers and die ranges for common actions differ from title to title. By contrast, the similarly multi-era AFdE (Au Fil de L’Epée) has all-purpose, all era tables, from which you simply pick the relevant lines. If you have the combat-related charts to all three MoI (Men of Iron) designs, studying them will reveal an economical but effective approach to changing how the armies fought – amongst other things, charges are carried out with greater or lesser enthusiasm depending, at least in certain cases, on what the target is; and a commander may have either a weaker or more effective brake on what threatens to run wild around him.

Overall, this approach to characterizing units is entirely acceptable – providing it keeps the key contingencies covered. The only area where this system has a notable wobble, in my opinion, is in the instance of infantry getting close to enemy cavalry – or perhaps, infantry putting itself in a cavalry-vulnerable state is a better term to use, given an Infidel map scale of 250 yards per hex. The game will certainly offer punishment to any player who moves poor or indifferent infantry units close to decent cavalry – it is likely, with a range of detrimental modifiers, to be well and truly pounded under hoof.

But there is no preclusion to moving your infantry to such a spot, and the only “punishment” is by the actual instigation of combat, not by any morale or formation hurt the mere presence of the cavalry might inflict. I must admit to being dubious about this, as for any unit type whose sole effective defense is to be somewhere else, acquiescing to march up close to the bad news in the first place seems a highly unlikely occurrence. Of course, you do not want a clean system cluttered (and by and large this is about as clean as they come), but slowing a unit by increasing terrain costs, or forcing a unit to flip (disorder) once it sees the gee-gees in the distance does not seem too much like clutter to me. If you want another simple analogy, the victims of the lions in the Roman arena would not wait till they were being mauled and chewed upon before they started to panic, run around and cry out.

This is not meant to imply, however, that infantry is utterly useless in these battles whatever the circumstances. On the march, Crusader infantry probably had a role as important as the mounted arm, if only to ensure, by warding the perimeter of the column, that the precious mounts were not shot to pieces. But there was little in the infantry “kit” at this point to enable it to negate the effects of the charge or get after a mounted arm in the way later generations could. Certainly, some of the change would rest upon evolving weapon technology, such as with the longbow, but considering the misfortune visited upon the haughty knight by long pointy bits of tree and sharp pointy bits of metal (caltrops), much probably had to do with changing mindsets rather than any massive leap forward in available weaponry. When we come to Bannockburn, we will see that Bruce and the Scots did not try to match the English knights as counter them with an alternative solution – a lot of mud, a lot of long pointy sticks, (far longer than one a knight could couch), and a generally cavalry unfriendly environment. Much the same is also true of Courtrai.

But back with the knights, and back in the Outremer (the Levant), a charge by just about any quantity of them, going in the right direction, was the most powerful thing on the field. There was seldom that many knights though, outside of a “current” crusade, because the feudal Outremer, such as it ever was, could hardly sustain any large number. One other game to cover battles from the time and area is Vae Victis’ Le Lion et L’Epée. This title, part of the company’s very extensive and growing medieval battles series, covers two engagements from the campaigns of Richard the Lionheart – according to Hollywood, a great hero of the English, according to the English, someone with about as much English feeling and sentiment as Charles DeGaulle.

But back with the knights, and back in the Outremer (the Levant), a charge by just about any quantity of them, going in the right direction, was the most powerful thing on the field. There was seldom that many knights though, outside of a “current” crusade, because the feudal Outremer, such as it ever was, could hardly sustain any large number. One other game to cover battles from the time and area is Vae Victis’ Le Lion et L’Epée. This title, part of the company’s very extensive and growing medieval battles series, covers two engagements from the campaigns of Richard the Lionheart – according to Hollywood, a great hero of the English, according to the English, someone with about as much English feeling and sentiment as Charles DeGaulle.

What is interesting is that despite presenting things its own way, the Vae Victis title and GMT’s Infidel are essentially the same in what they feature at the killing end of these armies “giving it large” on the battlefield – both have their combat matrices linked to unit type, both demand a form of quality check for charges, and both are very much about getting the right sort of modifiers into play. Of course, both systems are also very much at the “get set up and get playing” end of the complexity range, which is great, as the battles on offer from the Crusade era are full of enough atmosphere to whet anyone’s appetite.

What is clear is that putting just about anything in front of a charge by knights of this period was often like putting feathers in front of a leaf blower. But as I have said in other articles, when one is dealing with any “epic” era of warfare, such as one that presents leaders of the ability of Cœur de Lion and the presence of Saladin, it would be nice to have a bit more about them than numbers on a counter. In the scenario rules for the VV design there are some great bits of material about desperate lunges towards personal combat, with Richard getting bonked on the head, and also of the Hospitaliers’ commander finally ignoring Richard’s orders at Arsuf, and charging straight at the arrow-loosing tormentors. These things are at least given consideration in the game, portraying our men of the moment as more than better quality bits of cardboard. But as ever, I just wish there was more of this kind of stuff in designs generally.

The only real issues I have with AFdE as a series are that, again, all kinds of nondescript infantry can be moved within thundering hooves range of the enemy without any real penalty at that point, and that the cavalry types cannot evade the melee intent of the enemy by dint of being faster – something they certainly can do in MoI and the Markham designs. On the other hand, the mounted knights in AFdE can choose to dismount and fight on foot, whereas the “prepared” knight on foot is entirely a scenario at-start stipulation in MoI, and thereafter the only way “Dasterdly Jasper” comes off his horse is if his horse suffers an unpremeditated malfunction.

To the next era under review it is only a matter of a few decades (to the Barons’ War in England and to various complex disputes in the regions of France). Any decent book on armour and/or weaponry will chart the slow evolution of battlefield accouterments over that era. Advances in metallurgy, in bow technology and so forth, created their own cycle of advance in one area and response in another, culminating in the contest between longbow, crossbow and the armoured man and horse. But at the time of the Barons’ War and the other engagements of the same era, whilst infantry had grown somewhat in professional status, it could (literally) be hit or miss as to what effect it had in any given battle.

A look at the wargame OOB and certain scenario specifics for these battles offers insight into the character of the engagements. With Barons’ War (once you have drawn the elusive OOBs down from the ethereal mists – i.e. from Wallace’s War) there is a lot of infantry to hand for both sides, capable of holding its own against anything of the like on the other side, but which is going to go completely “Gadzooks” if enemy cavalry comes up close. This is reflected in both the melee modifiers as well as the utterly dismal missile ability of these units when the hooves are on the way. The designer, Rob Markham, does not present any actual missile units for these battles (Lewes and Evesham), but incorporates their often less than stunning presence within the function of standard infantry. As such, these units can launch ranged attacks against other like targets with some level of effectiveness, but against a declared charge, when horse, man and hurt are coming their way, what you get is a game representation of “throw and fluster.”

A look at the wargame OOB and certain scenario specifics for these battles offers insight into the character of the engagements. With Barons’ War (once you have drawn the elusive OOBs down from the ethereal mists – i.e. from Wallace’s War) there is a lot of infantry to hand for both sides, capable of holding its own against anything of the like on the other side, but which is going to go completely “Gadzooks” if enemy cavalry comes up close. This is reflected in both the melee modifiers as well as the utterly dismal missile ability of these units when the hooves are on the way. The designer, Rob Markham, does not present any actual missile units for these battles (Lewes and Evesham), but incorporates their often less than stunning presence within the function of standard infantry. As such, these units can launch ranged attacks against other like targets with some level of effectiveness, but against a declared charge, when horse, man and hurt are coming their way, what you get is a game representation of “throw and fluster.”

If I am interpreting things the right way, Rob saw the missile troops of this era, or at least in England, as not having the overall skill, status and organization to do more than “chuck it, twang it, and hope.” And although there are studies of the mounted arm in this era that argue that the use of cavalry on the medieval field could be rather sophisticated, it certainly was not in some of the most famous battles of the time. At Lewes (for American readers, this is pronounced much more like “Lewis”) the future Edward I led his cavalry with all the control and guile of a dog chasing after a ball. Driven by the hectic impetuosities of slighted honour, barely was his wing in array then he was off with the best men in his father’s army. He prevailed in the ensuing melee, but then he, his command, and his father’s hope, went riding off into the wide blue yonder and was gone for hours.

This infamous trait of English cavalry (think not only of Lewes, but also of Edgehill, Naseby, and Waterloo) is in this case created by an optional rule that commits Edward’s battle to attacking one particular enemy battle to the exclusion of any other target. That this is optional, and that the battle targeted is player-chosen, does seem like equivocation about presenting players with the difficult traits of many such battles. And it also will not take his battle entirely off the field, contrary to what actually occurred. Edward would grow into one of the most formidable military leaders in Europe, but here he acted like a complete idiot…like so many other chivalric nincompoops on many other fields. Considering how much effort designers put into modeling the performance of a Panther tank or the flight characteristics of an early Spitfire, getting iffy about modeling and presenting leadership traits remains an area of frustration. The rule is optional – so if you like, Edward does not approach the fight full of ire at perceived insults to his mother, and just acts out his part according to the numbers on his counter; but that is like taking the engine issues away from the Panther and the firepower/carburetor problems out of the Spitfire’s profile, and we know what gamers would think about that.

It can seem odd, but in the scope of “Western” military practice of the time, facing what was seen as a weaker host, or in any other way (including social) an inferior host, was often more replete with dangers to the aggressive side than confronting an army of equal stature. This was not only because it would prompt the supposedly better force into acting like a richly accoutered version of something that would go lumbering after Will Robinson and Zachary Smith once a week, it was also often the case that the apparently inferior force was far more dangerous than it looked.

This is not the place to go into the social divisions and tumults of medieval Europe in any detail, for it is sufficient to understand that less materially advantaged men and alliances, (but by no means unintelligent, or often that poor) needed to find a way of fighting their haughty adversaries that would suit their pockets and not demand too much of men and boys taken from their trades or fields to fill a line with reasonable effect.

The precepts of this were pretty simple:

1) Do not fight on terrain that suits cavalry.

2) Protect your flanks.

3) Hurt the charge long before it can hurt you and/or

4) At the very least, hearten your line and blunt the charge’s closing effect by natural and manmade terrain features, and by the employment of simple weapons with a greater reach than those of the knight.

What this meant when the lines formed was that providing the common man could hold steady with a long piece of sharpened tree, with a ditch or an expanse of boggy ground before him, and the same to either side; or, with greater skill, could loose a shaft alongside his companions, the cavalry were in dire trouble – not that they ever really thought they were until it was too late to think anything. In terms of this progression in war, Richard Berg’s first Men of Iron design comes into play now, as does that venerable offering, Agincourt, by Jim Dunnigan. But, just for a while, I will stay with the Markham designs, shifting from Baron’s War to Wallace’s War.

What this meant when the lines formed was that providing the common man could hold steady with a long piece of sharpened tree, with a ditch or an expanse of boggy ground before him, and the same to either side; or, with greater skill, could loose a shaft alongside his companions, the cavalry were in dire trouble – not that they ever really thought they were until it was too late to think anything. In terms of this progression in war, Richard Berg’s first Men of Iron design comes into play now, as does that venerable offering, Agincourt, by Jim Dunnigan. But, just for a while, I will stay with the Markham designs, shifting from Baron’s War to Wallace’s War.

I just want to add here that where the range of games does diverge in the handling of the charge is the extent to which terrain affects the ability to press the attack home. In the Berg series, adverse terrain (like the Courtrai ditch) strips the cavalry of its ability to melee with any charge modifier, but does not prevent some sort of attack going in. In the Markham series, there are some odd differences in the handling of terrain between the two games produced for Clash of Arms, but the essence remains that if cavalry cannot normally enter the hex/hexside, not only does the unit lose ability to charge, it cannot melee at all – heavy cavalry in this model can only deliver melee via a charge. AFdE is, surprisingly, very unfussy as to the charge “corridor” – the mounted quality can go pounding through most anything, perhaps losing movement factors as well as a level of combat effectiveness by ending up covered in bits of bush or a villager’s stew, but very little prevents a charge attack going in.

But now back to the battles of the blue-faced one…

In the two engagements presented in this game, Stirling Bridge (1297) and Falkirk (1298), one finds examples of both “the common man” prevailing, or with hope to prevail, against his titled adversary. We also see elements of combined arms in how the Scots were defeated at Falkirk (for now we do have archers as units in their own right) – and how they might well have been vanquished at Bannockburn if Edward II had proved less of an intemperate idiot commanding no respect among his knights and lords. Bannockburn, of course, is very much deserving of a mention, for bringing nearly all those “common” battlefield provisions into play, but I still want to tarry by Stirling and Falkirk to examine notions of army morale being affected (or not) by the fortunes of the “elite arm” – still very much the cavalry.

And I will first do this by shooting forward a little over five hundred years to Napoleon’s post-Waterloo excuses. There, in his own take on “the dog ate my homework,” the emperor constantly repeated the theme that the battle had been all but won, with only the English centre still holding, but that then, “an inexplicable panic” had seized the army, and total disaster had ensued. The panic, of course, was hardly “inexplicable,” as it was totally linked to a tired army, raised to boiling expectation by the advance of the Guard, then seeing “La Garde Recule,” and every hope dashed with their unlooked-for defeat. That was not how it was meant to happen – the Guard won battles, finished them off in other words; it was never meant to go into reverse with its battalions cut to pieces. But at Waterloo, that is exactly what happened.

So now, back to Wallace’s War. In the historical notes for Falkirk, the designer writes of how Wallace’s hopes for victory died as his reduced schiltrons failed to withstand the attacks of the English cavalry. What is strongly implied here, and would have been great to see in these games (but do not) is how one side’s morale can deflate faster than a punctured pig’s bladder in a village football game if the arm recognized as the prestige force of that army, the battle-winning rout enforcer, gets turned about and routed itself. Simply knocking morale down when this or that unit gets eliminated, or when unit X routs through unit Y is not the same thing.

So now, back to Wallace’s War. In the historical notes for Falkirk, the designer writes of how Wallace’s hopes for victory died as his reduced schiltrons failed to withstand the attacks of the English cavalry. What is strongly implied here, and would have been great to see in these games (but do not) is how one side’s morale can deflate faster than a punctured pig’s bladder in a village football game if the arm recognized as the prestige force of that army, the battle-winning rout enforcer, gets turned about and routed itself. Simply knocking morale down when this or that unit gets eliminated, or when unit X routs through unit Y is not the same thing.

Even though much of the English victory at Falkirk was due to the archers and the infantry, the cavalry were the glory boys, and how they went, so went the army. A number of Napoleonic designs have sought to present the morale impact of the Guard “going in” and possibly “running out” after a bit. So, imagine the frisson of sending the mailed fury of Longshank’s cavalry into the fight WITH the danger that if they turn about, your army and your winning position could all end up like so much Scotch mist.

Richard Berg’s original Men of Iron design covers Falkirk, as well as Courtrai and Bannockburn. The Berg take on Falkirk presents the infantry-heavy and largely immobile Scottish army as a kilted version of sitting ducks, ready to be disposed of by a combination of properly handled English archers and cavalry under the watch of the mature Edward I. Morale issues are a simple matter of measuring losses against a specified break level, which again leaves issues of the defeat of the elite arm well out of the calculation.

However, in the same game package, Courtrai and Bannockburn demonstrate what occurs when adverse terrain and chivalric arrogance combine. Despite the nature of the field, “Proud Edward’s Army” had every chance of winning at Bannockburn, as a clear process of gaining the day was staring the brash weakling in the face. But, as he could not co-ordinate the army, and control his own hotheads, he was not destined to win anything. As for ourselves, we can at least partly occupy our minds with that question dangling at the end of a Scottish pike – to wit, just how mobile or how static were these Scottish schiltron formations? The Berg interpretation, as seen in Men of Iron, is that they were essentially fixed in place. But in the Markham model the schiltron units can move (they actually have a printed movement factor, albeit not a very speedy one); and to this one might add that the recent and rather well done Bannockburn drama documentary, which featured contributions from, amongst others, the highly experienced military commentator Dr. L Nusbacher (author of a book on Bannockburn), also referred to mobile schiltrons. It may be hard to make a definite call on this, especially with regard to what is going on with formations on a wargame map, but at the least I suspect that the Bruce was able to train his men to do more than stand still and keep their pikes straight.

Returning to the cavalry, whether the elite arm’s misfortunes prompt a rout among “les autres” may well depend on what else is present on the field; but whatever the permutations, how that arm acts, or fails to act, will often have massive consequences. Of course, at Bannockburn, the repulse of the English mounted arm would only have served to further discourage a host that was in a floundering mess anyway. And at Crecy, the Berg design leaves a mass of mounted French nobility to play out their own near exclusive ruin their own way, as there is nothing else on the field save the Genoese crossbowmen, that the French clearly did not give a ducat for.

Men of Iron’s Courtrai specifically refers to the contempt the French nobility had for their lower class foes; but those foes had terrain, training and equipment on their side, none of it very sophisticated, but all of it highly effective. In game terms, every modifier advantage the French might have in open ground against their foe is here taken away from them entirely.

Men of Iron’s Courtrai specifically refers to the contempt the French nobility had for their lower class foes; but those foes had terrain, training and equipment on their side, none of it very sophisticated, but all of it highly effective. In game terms, every modifier advantage the French might have in open ground against their foe is here taken away from them entirely.

Inevitably, anyone coming to this subject today will wonder way the bitter lessons of experience did not encourage the baron in his castle to try something other than what was repeatedly failing? The short answer to that is that they generally tried two things: to provide the man and steed with improved armour; and to further expound the chivalric code by offering ever greater sacrifice and valour to getting it right – which is why they kept getting it wrong.

The history of the evolution of armour and what tries to pierce it is a massive subject, to which many fine books have been dedicated. Undoubtedly, the armour of the latter part of the Hundred Years War was far more complex and effective than what was sported by the nobility and their “people” at Lewes or Evesham, and it has been very much part of the academic to and fro as to just how effective many an infantry weapon was against it. In fact, if we are talking about the simple matter of armour being effectively holed and flesh effectively entered by arrows, there is plenty of evidence that a good deal of armour for the man and his mount was capable of withstanding missile impact – albeit at the cost of losing vast amounts of vision and (debatable) amounts of upright mobility.

But that is not the entire story by any means, given that the most famous battle of that long war, Agincourt, ended in utter French defeat. To understand what happened in a battle where most of the French knights were on foot in their highly expensive “complete armour,” one needs to know that not every English arrowhead was intended to make a hole and hit home “to ye vitales.” Many of the arrowhead designs were about making a smashing, perturbing, unbalancing impact – capable of knocking a man off his horse or the dismounted knight off his feet. You only need to imagine those thousands of shafts incessantly whacking against a tight-pressed line on boggy ground to comprehend why so many of the French dead expired through suffocation rather than being punctured by the saucy sharp weapons of their social inferiors.

At Courtrai, as Richard Berg states, the Flemish army was short of bowmen of any description, but through the office of the ditch they stood behind and the use of the goededaag, (a weapon all about yanking any rider from his horse), they achieved a more than acceptable effect. This is a case where a weapon/tactic is presented in a game by means beyond either a terrain effect or a modifier on the matrix – in these circumstances, repulsed French cavalry has a serious chance of becoming a dizzy unhorsed knight with no proper facility for seeing anything or moving anywhere; in other words, a sitting target.

One theme certainly worth bearing in mind is that whilst armour became increasingly sophisticated (as well as hideously expensive), and was the product of very clever men doing very clever things with hammers, presses and sooty blasts of heat, the responses generally tended to be simple, effective, and a fraction of the price. A longbow is a beautiful thing, but cost-wise, probably the equivalent of a box of matches compared to the small fortune a decent bit of metal suit would set you back. And then there would be the poleaxe, another bargain, the four-in-one wonder weapon, capable of hauling a man down, and then hacking, hammering, hewing or holing him into total incapacity.

On reflection, we should not be surprised that nobility about Europe cleaved to chivalric codes all the tighter even as the fallacies of the ethos screamed out at them. Chivalry was the manifestation of status allied to religious fervor, and to act chivalrously was a definition of class, a promoter of reputation, and a means to heavenly deserts. Without skewing things too much, one might wonder if winning a battle came ahead of dying gloriously in it? And as one commentator said, comparing French disasters at Crecy and Poitiers to what would occur at Agincourt, the perception among the French was that their forebears had failed not because their tactics were fundamentally flawed, but simply because they had not been chivalrous enough in seeing the charge home, and thus the resistance to effective change, with its de facto overthrowing of precious beliefs, was immense.

And so we come to an October day in 1415 via a summer day in 1978 or 1979, when I bought SPI’s Agincourt. To be honest, that is not the only Agincourt game I possess, as I also have the MoI “extra” included in C3i. However, that offering is a dinky little thing, with the game play best described as “set the French units up…and then take them all off again.” That, in small, is certainly the story of the battle, but hardly much of an experience as a game, nor much of an attempt to create the ambiance of this so famous medieval battlefield – something that the James Dunnigan SPI title aimed to do in plenty.

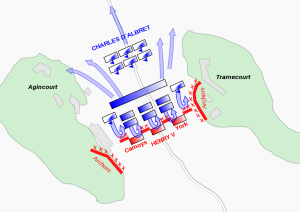

In the historical scenario, the battle opens with the English, having completed an advance of several hundred yards, then loosing volleys of arrows into the French ranks. The ensuing charge by the French mounted wings is baked into the system – no choice, no ifs or buts, the arrows are loosed and the charge follows. What is interesting with this is what a simple set of mechanisms, backed by some fascinating historical notes by Al Nofi, tells us about the two armies. The charge rules in this game are close to being the simplest I have encountered, and there are just the two French wing units (just a few hundred men all told) who are going to thunder forth. On the other hand, this simple process speaks volumes as to the absolute idiocy and headstrong arrogance of the entire host. French cavalry had charged and gone “Zut alors!” on one battlefield after another, and yet, despite the bloody precedent of repulse after repulse staring them through the visor, off they went again, in limited number, supposedly to achieve what thousands had failed to do not only against the English, but against the Flemish and other adversaries as well.

This, in essence, is more than a straightforward validation of the charge mechanisms we have thus far seen– for here the reaction charge is truly a reflex action devoid of thought or any calculation. The French cavalry, such as it was at Agincourt, had been meant as a flanking force, to compromise the English line as that line was originally, further back, with no helpful terrain anchoring it at either end. However, thanks to the mindset of the French as the English upped stakes and went forward, a mindset whereby a French knight/man-at-arms was more likely to strike a fellow Frenchman for a place of honour than deal with the vulnerable men under the Cross of Saint George, they first missed that opportunity to hit the English army when it was out of position, and then pressed forward as if the battle plan they were supposed to be following had been no more than a jest passing through one ear and out the other.

This, in essence, is more than a straightforward validation of the charge mechanisms we have thus far seen– for here the reaction charge is truly a reflex action devoid of thought or any calculation. The French cavalry, such as it was at Agincourt, had been meant as a flanking force, to compromise the English line as that line was originally, further back, with no helpful terrain anchoring it at either end. However, thanks to the mindset of the French as the English upped stakes and went forward, a mindset whereby a French knight/man-at-arms was more likely to strike a fellow Frenchman for a place of honour than deal with the vulnerable men under the Cross of Saint George, they first missed that opportunity to hit the English army when it was out of position, and then pressed forward as if the battle plan they were supposed to be following had been no more than a jest passing through one ear and out the other.

As for the units the game supplies to perform this folly with, a charging cavalry unit is flipped to its higher strength and then performs its charge. The next interesting thing is the handling of terrain. We have already encountered various degrees of terrain stringency or laissez-faire in the other designs as the horses snort and the knights thunder and blunder about, but the Agincourt design offers something more. Essentially, the field is empty, but it is muddy, and it also dips mildly from the French to the final English position. In the normal run of things, going by other game experiences, one would think nothing of this as it would do nothing – but in this design, you cannot charge through a descending contour. I find this fascinating, and by my interpretation I would tend to believe that it is both mud and going downhill that is the problem – basically, the charge would end up like a comedy clown act at the circus.

One thing that is certainly worth referring to out of the game’s accompanying notes is how the two armies set about the process of fighting on foot. The English were long used to it, and accepted it as their way of war. However, although the vast majority of the French army was also on foot, with the exception of the crossbowmen one gets the distinct impression they would all far rather have been up in the saddle – irrespective of the realities. One piece of evidence for this is that the French had shortened their lances to enable them to have a weapon more akin to a pike. But the very fact that they did not have a proper pike in the first place, or any notion as to how to dress a line of foot so that it might fight with efficiency and not go forth like so much tangled scrap metal, really does give the game away. And while it is often stated that King Hal had to close the distance to get the battle going, there was probably not a great deal wrong in stopping where he first was, for either the French would have started fighting among themselves, or, had they finally advanced, going eight hundred yards totally soused and in an tight pressed disarray, would have done most of the English army’s work for them.

In the end, it hardly mattered, because the French went down to the worst defeat of the war, part of which was the total destruction of their cavalry wings. To make a game rather than a study experience, the design, as I have already said, offers a range of what-ifs, from free French set-up, to Hal attacking, to a different (but still muddy) field. But whatever the hiccups in the system, this remains an amazing look at one particular battle; for unlike the other designs, this one would not readily translate into a recreation of just about anything else from the period we are studying, as, at least in my opinion, the systems here are too tailored, too specialized, to comfortably hop into something else, beyond possibly Crecy or Poitiers. But for Agincourt, providing you understand that this is a study more than a game, it is a quality piece of work.

For the latter part of The Hundred Years War, as well as other French broils, we are back with AFdE. The system remains as it was, but a greater diversity of units are now fitted in it, as the smoldering linstock and the smell of sulfur make their presence known upon the field. If you look through the counter manifests for any of these battles, the mounted knight is still there, but these are very different armies overall to anything on the receiving end of a “Twang, Swoosh, Eurggh!” at Crecy. And having, at least to some extent, given up on fighting the French, it was the turn of the English to fight among themselves, and this on the miserably prolonged scale of the Wars of the Roses.

For the battles that end our period of study, the game is Blood and Roses, being the third of the Men of Iron series. Two things are readily apparent in this series of Wars of the Roses battles – the preponderance of infantry over cavalry, and the designer removing the charge reluctance provisions that are present in the earlier games of the series. The game rationale for this is that infantry weapons of this period were not of the type that could be presented as a mass of gleaming sharp points which would deter a charge being pressed home – and also that the armour for man and horse in this late medieval world was simply far more effective.

All of this sounds perfectly logical, but as we have already seen, the medieval man on his steed was not the most logical of beings. In MoI, depending on the precise era and the army in question, you can sometimes put the brakes on a bunch of intemperate knights, but that is only part of the story. It is, of course, a fact that in near all circumstances, a horse is not going to dash headlong into an array of gleaming points, but that is not the same as a charge never getting going in the first place. It may, in fact, falter at the end, at the moment of delivery. The games vary in coverage of this issue – MoI sees such attacks go in, but weakened by dint of losing their charge status; the Markham designs do not really deal with this, you either charge with full effect, or stop where you are by volition, and it is the same with AFdE. With counter/reaction charges, however, all three of these systems usually call for a die roll to be passed, otherwise your force will remaining on the receiving end of whatever is arriving.

And on that issue of receiving things, often very nasty things, we must surely also consider the infantry, often reluctantly looking at what is thundering forward – only the games have not too much to say on this.

I am going out of era here, but it is worthy of note that British officers of the Napoleonic era did sometimes comment adversely on their men’s ability to hold firm in square when faced by a charge. Despite the fact that they were in the optimum formation to receive cavalry, officers at various levels described the men as becoming “twitchy” and shuffling about, rendering the cohesion of the square doubtful. This, on occasion, led to cavalry entering the square (this appears to have occurred at Quatre Bras – though not to be confused with incidents in the battle when squares failed to form in time), and so, as I suggested much earlier in this article, one can make the criticism that infantry, even not very good infantry, is getting away with a bit too much as these systems stand, and should need their own morale checks in these circumstances.

Just to further illustrate this by way of an interesting anecdote, most of us will have seen the film Waterloo, and I will not have been the only person who thought it silly that the spectacular charge of the Scots Greys spectacularly charged into a big empty space utterly devoid of the French infantry they were supposed to be routing. But the truth is the director, the great Sergey Bondarchuk, had arranged all the shots of the infantry falling back in panic from the cavalry, but could not get the Soviet infantry extras to face their Soviet cavalry extras in any way that would make the scene work. In fact, despite having clearly marked (taped) charge lanes for the cavalry, the infantry would not agree to take part, and so the entire set of shots had to be scrapped. Such is the psychological impact of a mass charge.

Staying in the Napoleonic era, some of the most interesting charge mechanisms I ever encountered were to be found in Wellington’s Victory, where much anything that found itself in a cavalry unit’s charge zone, moved slower than units elsewhere (a reflection on the speed of the charging horse compared to a man on foot), and also had to undergo a test of morale.

Whether adding these sorts of factors to the charge mechanisms of any of the games would have added more than administrative clutter, may well be a matter of individual taste. But they are issues worthy of consideration, if only because, inevitably, another designer will one day want to turn their attention to the battles of medieval Europe, and will be faced with the challenge of what to put in, and what to leave out – though seeking to put everything in has never been a good idea.

And having reached the end of our era, among the snow storms of Towton and rough goings-on up Saint Albans’ high street, one might have thought that the mounted man was well and truly on his way out – rendered redundant by stakes, pikes, caltrops, guns, longbows and something approaching commonsense in the era of the Renaissance. But that is not what happened, because armies still needed the mobility that only the horse could provide, wanted the psychological intimidation that only the horse could provide, and then, once the rider had weapons and tactics that enabled the mounted arm to be effective again, the cavalry was back with a vengeance – put onto the wings of armies during conflicts such as the Thirty Years War, where, if it did engage infantry, it was from the flank and rear, and with its own supporting infantry close by. The cavalry pistol enabled the cavalryman to inflict hurt beyond the range of a pike, and the general intention was for cavalry to fight other cavalry and then help the infantry finish the day by breaking the enemy foot. Of course, the armies of the Middle East had been twanging away with mounted, ranged fire for centuries, but the armies of Europe, in the pre-gunpowder age, never quite got the habit. As for the later eras, Napoleonic cavalry hardly ever went in first, but was kept back to finish what the infantry and artillery had started; and as for the American Civil War, the first thing a cavalryman did in many battles was get off his horse and reach for his firing piece.

One thing I do want to stress before I end is that this has not been intended as a review of the games I have brought into the discussion. There is a great deal in all these designs I have not mentioned at all, because this is an article specifically about what medieval cavalry did and how games have portrayed it. The three design series each have their merits, very much so in certain aspects, whilst Agincourt is an outstanding recreation of one of the biggest pieces of military idiocy in history. The “pulse” and the clean look of the Men of Iron series is not to be undervalued; and the gorgeous look and scope of AFdE is well worthy of attention.

One thing I do want to stress before I end is that this has not been intended as a review of the games I have brought into the discussion. There is a great deal in all these designs I have not mentioned at all, because this is an article specifically about what medieval cavalry did and how games have portrayed it. The three design series each have their merits, very much so in certain aspects, whilst Agincourt is an outstanding recreation of one of the biggest pieces of military idiocy in history. The “pulse” and the clean look of the Men of Iron series is not to be undervalued; and the gorgeous look and scope of AFdE is well worthy of attention.

By contrast, the Barons’ War/Wallace’s War series is a bit more fussy, and added to the original rules issues, has never been as popular. On the other hand, I could not possibly have done this article without including these works. Agincourt I would recommend to anyone who wishes to see a working model of a great battle – it may not be much of a game, but it is very good history. As for the cavalry of Eastern Europe, I would love to have included something on the subject, but there really is not much around – I do have the ATO title Kulikovo, but as it uses the MoI model, there is not a great deal to add. The Devil’s Horseman was another alternative, but as I do not own it, and it contains some battles far beyond the remit of this article, I felt I could not include it. Nevertheless, the article, as I present it here, should give plenty of food for thought, and in that spirit I hope you enjoy it.

Paul Comben

Not disagreeing with your general thrust, but a couple of points. You note that the French kept charging with their chivalric cavalry despite repulse after repulse – this is true and false. They did suffer many defeats at the hands of the English archers and Flemish foot…..but they also had many crushing victories (Muret, Beneventum, Tagliacozzo) against armies similar in composition to the English, just not as skillfully led.

A second point is not really addressed by you, but needs to receive more attention. Studies of the French and English agricultural economies in the middle ages (14-15th centuries) have raised serious questions as to the sizes of the armies. While it has long been known that chronicles exaggerate, numbers like 30000 have been accepted for the French at Agincourt or Crecy, and 50000 total combatants for battles like Towton. These studies have demonstrated that the armies of the time CANNOT have been close to these sizes for the most compelling of reasons: the economies of the areas campaigned in could not have supported feeding such armies for more than a few days. The governments in question could in theory procure food in other places to support these armies, but there is no evidence to suggest that they did this, despite fairly complete expense records in both kingdoms for these periods.

Points aside, thank you for your article!

Good points Matthew.

With regard to the first, I think the lesson is that if doctrine stifle or incompetency overtake any force, whatever power it had may often fall to naught.

On the second point, I wondered if you had read Hans Delbruck’s histories? He very much professed the effects of culture and economy in determining an army’s size. He too readily dismissed fanciful and bloated army registers. I think the best example I could offer is some dreamy historian twenty five centuries from now insisting Britain went to war in 1914 with an army of ten million because, well, look at the size of her empire!

Thanks very much for the article Paul, I really enjoyed it.

My pleasure.

I will be doing something Napoleonic next time which I hope you will enjoy also.

I enjoyed reading your article. Your comment about the response of the mounted knight to stress the chivalric code chimes very well with miltary thought prior to World War One when faced with the increased power of weapons; their view was that they needed to resort to methods to improve the morale of the troops so that they would reach then enemy’s line.

Hello Andrew

I will very much be staying with pre-gunpowder battlefield environments for my next article on this site. A three part game study, you should find it interesting.

Glad you liked this piece. Paul.