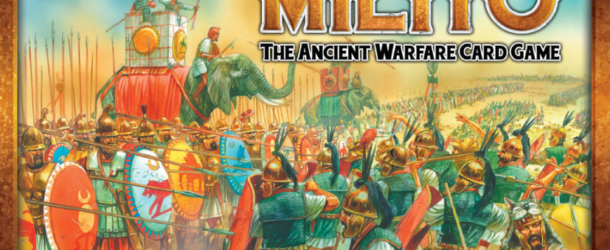

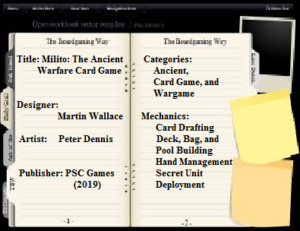

Milito

By Paul Comben

Perhaps for many people, British designer Martin Wallace is associated first and foremost with games about aspects of industrial history and trade. On the quiet, however, the number of wargame-related titles he has produced has been steadily growing over the years. A hallmark of these, and perhaps of his work in general, is that it is rare for any two of his design models to look like anything else in his catalogue. I own several Mr. Wallace’s wargame designs, including his unique renderings of Waterloo and Gettysburg as well as the more recent but equally idiosyncratic Lincoln.

But what of Milito? Perhaps it is stating the obvious to say that it is different again – totally card format, with six armies from the ancient era ready to do battle in whatever combination you choose. The armies in the box, each consisting of just over twenty cards representing a variety of troop types, will offer you three historical matchups – Britons against Imperial Romans, Republican Romans against Carthaginians, and Greeks (Alexandrian/Macedonian) versus Persians, but the design really does work around the invitation to create whatever battle you will involving forces that never historically met. This is a game designed to play fast, be fun, and take up a modicum of space. The “battlefield” itself is created semi-randomly by drawing five terrain cards from the small collection provided – most cards are depictions of open plain, but the chance exists of encountering combinations of rough, wooded, and hill terrain to be placed upon the battlefield’s edges. Plains cards always go in the centre of the created array, while anything else is placed upon the flanks following a few simple guidelines in the rules. You then randomly select an initial nine cards from your army deck and decide who will go first – flip a coin, etc. The winner of the game is the first player to control three of the five terrain cards come the next victory check in the game sequence.

But what of Milito? Perhaps it is stating the obvious to say that it is different again – totally card format, with six armies from the ancient era ready to do battle in whatever combination you choose. The armies in the box, each consisting of just over twenty cards representing a variety of troop types, will offer you three historical matchups – Britons against Imperial Romans, Republican Romans against Carthaginians, and Greeks (Alexandrian/Macedonian) versus Persians, but the design really does work around the invitation to create whatever battle you will involving forces that never historically met. This is a game designed to play fast, be fun, and take up a modicum of space. The “battlefield” itself is created semi-randomly by drawing five terrain cards from the small collection provided – most cards are depictions of open plain, but the chance exists of encountering combinations of rough, wooded, and hill terrain to be placed upon the battlefield’s edges. Plains cards always go in the centre of the created array, while anything else is placed upon the flanks following a few simple guidelines in the rules. You then randomly select an initial nine cards from your army deck and decide who will go first – flip a coin, etc. The winner of the game is the first player to control three of the five terrain cards come the next victory check in the game sequence.

It is some measure of how simple Milito is to learn that, having taken the game to a friend’s home recently, despite having never played any wargame of any description, she (Karen) was pretty comfortable with play after a short introduction followed by the first few rounds of battle. Where Milito’s complexity comes into effect is via the decision-making that is required to make the best use of your hand and the circulation of cards into and out of it. All six armies have strengths and weaknesses, and bad play will see some quality troops heading into the eliminated pile rather than simply being placed in the discard deck ready for another deployment later.

To a not inconsiderable extent, getting a feeling for the game’s tempo is key to playing well. This involves looking beyond what you can hit to consider what might then hit you even harder unless you have something lurking in your deck (like a combat-effective leader) who can bolster your line with a bonus if on the defensive. No more than two cards from the same army can vie for any area, and even then, they must be of the same unit type or be the sort of skirmishing light/missile troops than have a combination ability depicted on their card.

To a not inconsiderable extent, getting a feeling for the game’s tempo is key to playing well. This involves looking beyond what you can hit to consider what might then hit you even harder unless you have something lurking in your deck (like a combat-effective leader) who can bolster your line with a bonus if on the defensive. No more than two cards from the same army can vie for any area, and even then, they must be of the same unit type or be the sort of skirmishing light/missile troops than have a combination ability depicted on their card.

For our initial battle, Karen commanded a host of Britons (all chariots and surging barbarian infantry) against my Imperial Romans (including some very deadly heavy infantry…providing whatever it is facing does not/cannot get out of the way of its slow progress.

Let us now look at the sequence of play – the first player performs the following phases in sequence, and these are then repeated by the second player.

- Victory Check The active player can win at this point if they already have three terrain cards (called columns in the game) in their control. Tempo comes very much into play here, as the active player may be facing imminent defeat but will still have their whole turn to remedy the situation. Whether they can or not will largely, but perhaps not entirely, depend on what they can bring into play via their hand. Face this situation with sparse forces in a depleted hand and you are in serious trouble.

- Advance This is not, as you might assume when you bring new forces into play, but when control of terrain changes. If you are facing a terrain card with forces that have nothing directly opposing them, the card is moved to your favour – i.e. it is turned so that its control facing is pointed to your units. As this happens when it does in the overall sequence, clearing a card of opponents later in the player turn phases does not necessarily imply it is going to turn to you – your opponent may get a chance to contest it again or even clear you off the position altogether.

- Flank Attacks Both Karen and I saw forces chewed up by these nasty attacks. If you have forces facing a target “position” plus forces unopposed one column along, you can attack the target with either the directly opposing force or the adjacent force. In either case you get a +2 to your combat strength – more on resolution a little later. One key aspect of making flank attacks is that you must go in with what you presently have on the table and in the right locations. Unlike “orthodox” attacks in the next phase, you cannot bolster your intended melee with additional forces from your hand – except leaders, which are a vital resource although some armies have a better quality that way than others.

- Player Actions, In theory, you can empty your hand in this phase, loading columns with forces up to the maximum, declaring attacks, and adding leaders to give your combats that desired final edge. But note, it all comes at a cost. Some combat units require discards to be taken from your hand or your draw deck in order to get them into play – this can be expensive with some of the dangerous but somewhat plodding units, reflecting both their lack of speed and general manoeuvrability. Terrain can also affect costs or prevent the placement of units in the first place – e.g. no chariots in rough terrain. And included in the finer subtleties of the design is the dubious merit of stuffing a location full of big lads. Only your chosen lead unit will get to do anything with its full combat value, while both units will suffer whatever woe comes that location’s way. Better tactical mixes are missile troops with whatever they can assist. However, just to add a little more complexity along the way, Karen’s Britons, as seen in our battle, did have a limited leader ability to combine a couple of units of the same type into the same combat. Depending on what you are facing, or think you are likely to face, placing a lot of cards may or may not be a good idea, though as there is a strong element of hand management in play here, virtually exhausting your hand and relying on a three-card replenishment to tide you over is not always going to be a good move.

- Draw Cards Take up to three cards from the draw deck – ensuring your hand is not increased beyond nine. Reshuffle your discards if you are out of fresh draw cards to make a new draw deck. Note, this also acts as a form of timer, as for the Britons, their main infantry loses a combat bonus once this shuffle occurs – i.e. they are out of momentum and first fury.

A potential flanking chance for the Britons. The two circled cards can, per rule, combine to attack their direct opponents, adding the +2 bonus for the flanking situation. Alternatively, one card from the group with the arrow can make the attack, again with the bonus. The other infantry merely adds +1. If the right British leader is played, both the infantry cards can fully combine.

A potential flanking chance for the Britons. The two circled cards can, per rule, combine to attack their direct opponents, adding the +2 bonus for the flanking situation. Alternatively, one card from the group with the arrow can make the attack, again with the bonus. The other infantry merely adds +1. If the right British leader is played, both the infantry cards can fully combine.

—————————————————————–

One thing that is apparent from early study and play is that a great deal of work has gone into making the armies perform differently. This is more than simply a matter of details such as the Greeks having heavy pikemen and the Persians and the Britons having chariot forces with their given numerical values. Many of the forces are further shaped by a brief description of a particular ability or restriction at the foot of their card, and indeed, not all the combat cards have a numerical value for all the potential capacities the game presents.

The best way to present this simply is to take a look at the following illustration of sample forces drawn from four of the armies – Persian, Imperial Roman, Alexandrian/Macedonian and British.

The Greek Pike unit is the slowest unit in the box (0 relative speed) but is very strong in combat, both in attack and defence (next two ratings). To be deployed from the player’s hand means discarding two cards from that hand or the draw deck. Engaging in a flank attack again requires a discard, while the big weakness is a -3 to defence value if being flanked. Add that to the +2 the flanking attacker will get for their own force and the pike unit is a near-certain casualty. To the right, the Persian Heavy Cavalry is far faster (in-game terms it gives it a better chance of preventing targeted units from withdrawing or giving itself a better chance of evading hurt). The Imperial Roman Archer displays a chain-link symbol meaning it can deploy in a location alongside any other unit type. Note also its advantage deployed on or next to a hill location (bottom of the card).

The Greek Pike unit is the slowest unit in the box (0 relative speed) but is very strong in combat, both in attack and defence (next two ratings). To be deployed from the player’s hand means discarding two cards from that hand or the draw deck. Engaging in a flank attack again requires a discard, while the big weakness is a -3 to defence value if being flanked. Add that to the +2 the flanking attacker will get for their own force and the pike unit is a near-certain casualty. To the right, the Persian Heavy Cavalry is far faster (in-game terms it gives it a better chance of preventing targeted units from withdrawing or giving itself a better chance of evading hurt). The Imperial Roman Archer displays a chain-link symbol meaning it can deploy in a location alongside any other unit type. Note also its advantage deployed on or next to a hill location (bottom of the card).

The British Leader can add +2 to combat to which it is assigned, or act as one card for discard costs. Not all leaders in any army are the same – some have qualities expressed in text, while some have better discard values, and one of the British leaders is a negative combat presence – too much bellowing and beer! The British Chariot is fairly fast, better at attacking than defending, but is not so good against light infantry and cannot enter rough or woods terrain.

Note: Leaders do not get to occupy locations on the battlefield – they get played at the relevant instant to cover discard costs or to help support combat.

Cards defeated in combat are permanently eliminated. Cards a player chooses to withdraw or must withdraw are recycled via the eventual reshuffling of the discard deck once there are no fresh cards left to draw.

—————————————————————–

Being the player to start the game off is rather challenging – or at least I thought so! My inclination is that you need to get all five terrain columns filled to avoid early flanking disasters, but at the same time it will not help matters if you cannot deploy anything with a bit of weight to it in most of those locations. It is tempting to think that if you are going to start with a shorter line and with an open flank, it better include something tough that can be backed by a good leader if combat subsequently arises, or, if you have one of those really honed armies as your deck, you have a leader already in your hand whose special talent is to conduct an effect withdrawal if things begin to look dodgy. Then again, taking hits and losing cards is virtually unavoidable – sometimes it seems that the key is being able to hit back even harder.

So how precisely does combat work? It can sound incredibly simplistic to say whoever has the larger final value wins, but that is the gist of it. On the other hand, making it to that larger value, or even commencing combat in the first place, is another matter and one that can get a bit complex in terms of the ramifications.

Consider the following:

Player A is commanding Alexandrian/Macedonian forces and, in their turn, deploys a powerful but slow as treacle pike card opposite Player B’s Persian cavalry card. From Player A’s perspective, the good news is that providing the pikes’ flanks are secure, the card is going to be immune to just about any attack. The bad news is that Player A’s pikes will not be able to attack Player B’s cavalry unless Player B agrees to the combat – the likelier option is that the massive difference in speed will lead to the owner of the Persian unit withdrawing it (going in the discard pile). Of course, it must be remembered that you do not win the game by destroying enemy cards; rather you win by gaining terrain columns. Thus, a terrain card that is vacated by this or that force is ripe for being taken over. But with Player B set to play next, they could now contest the column again – either with another fast card flitting around like a fly you can never quite swat, or with a bit of heavy stuff of their own that they might just be able to bolster with some missile troops and/or some first-rate leader they have yet to disclose.

Player A is commanding Alexandrian/Macedonian forces and, in their turn, deploys a powerful but slow as treacle pike card opposite Player B’s Persian cavalry card. From Player A’s perspective, the good news is that providing the pikes’ flanks are secure, the card is going to be immune to just about any attack. The bad news is that Player A’s pikes will not be able to attack Player B’s cavalry unless Player B agrees to the combat – the likelier option is that the massive difference in speed will lead to the owner of the Persian unit withdrawing it (going in the discard pile). Of course, it must be remembered that you do not win the game by destroying enemy cards; rather you win by gaining terrain columns. Thus, a terrain card that is vacated by this or that force is ripe for being taken over. But with Player B set to play next, they could now contest the column again – either with another fast card flitting around like a fly you can never quite swat, or with a bit of heavy stuff of their own that they might just be able to bolster with some missile troops and/or some first-rate leader they have yet to disclose.

—————————————————————–

The fundamental truth behind this is that ancient battles were often a lot of thump and crash at one level, and a challenge of precise timing at another. When to commit and what to commit is all part of that, and in its own way, so is sizing up your battlefield as the turns go by, holding onto something key and resisting simply playing it because it looks good, and yes, even counting cards if you feel up to it.

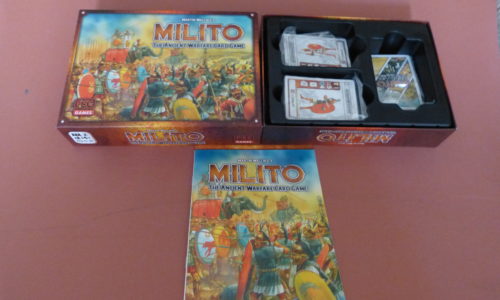

How do I rate Milito? As I said earlier, I was able to get Karen into the swing of things after a few minutes’ chat with the cards in front of us, and then we played with me helping her to choose better cards and explaining some historical bits and pieces as we went along. And it all went along very nicely. By the time a few turns had gone by, she was getting into the game and readily expressed her willingness to play it again. And that is one of the best things I can say about the design – it plays fast and with enough historical accenting to feel valid on its own terms. Yes, you can play with forces that never met in the real world, but that is hardly the point. It is a perfectly good change of pace game, a filler, a fun introductory title, but certainly not bland or banal. It sat in its attractive little box in the car, was set up in less than a minute, and was played with plenty of time spare for another go with different armies. It is nice to have a few games like that.

How do I rate Milito? As I said earlier, I was able to get Karen into the swing of things after a few minutes’ chat with the cards in front of us, and then we played with me helping her to choose better cards and explaining some historical bits and pieces as we went along. And it all went along very nicely. By the time a few turns had gone by, she was getting into the game and readily expressed her willingness to play it again. And that is one of the best things I can say about the design – it plays fast and with enough historical accenting to feel valid on its own terms. Yes, you can play with forces that never met in the real world, but that is hardly the point. It is a perfectly good change of pace game, a filler, a fun introductory title, but certainly not bland or banal. It sat in its attractive little box in the car, was set up in less than a minute, and was played with plenty of time spare for another go with different armies. It is nice to have a few games like that.

Paul Comben

Game Resources:

Milito BGG Page:

Milito Home Page: