By Gary Andrews, Harvey Mossman and Fred Manzo

OR

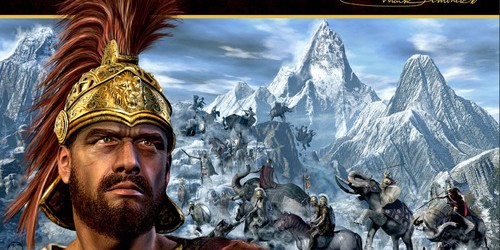

Why Hannibal: Rome vs Carthage is the best Card Driven Game (CDG)

ever published

The cards in a CDG wargame are typically used to move armies, generate random events and produce some Fog-of-War. Now, while the Card Driven Game concept is generally considered to be one of the most important advances in boardgaming over the last 30 years, not all of the designs using this system are equally successful. The proposition of this article is that Card Driven Games create tense, well fought contests only when they follow 6 basic principles.

The cards in a CDG wargame are typically used to move armies, generate random events and produce some Fog-of-War. Now, while the Card Driven Game concept is generally considered to be one of the most important advances in boardgaming over the last 30 years, not all of the designs using this system are equally successful. The proposition of this article is that Card Driven Games create tense, well fought contests only when they follow 6 basic principles.

They stress:

Elegance: Obviously, asking for elegant games is not the same as asking for simplistic games. Elegance is having a minimum number of simple rules produce a maximum number of intriguing options. One way Card Driven Games achieve this is by placing some of their rules on cards as alternatives so that they interact in various ways with the rest of the system depending on when and how their card is played.This approach has many advantages. First, it enhances the dramatic quality of a game as players become aware of unfolding stratagems only when the game proceeds. Second, if a particular card isn’t dealt, players do not have to spend time considering any special rule it contains. And third, it increases a game’s level of tension, as highly involved mechanisms either halt play while people argue about their finer points or everyone must memorize all their intricacies. THIS IS NOT FUN.

Unfortunately, some do not see the CDG concept as a method of streamlining games but as a chance to increase their complexity through the extra resources such designs require. That is, while a non-CDG game might have, say, a total of 20 pages of rules on 20 pages of paper, we now are getting wargames cluttered with 23 pages of rules simply spread over 20 pages of paper, a few player’s aid sheets and 55 cards. In some ways, it’s an improvement but it doesn’t use a game’s assets to their fullest potential. Eloquence counts for something.

Depth: The primary job of event cards in a CDG is to create simultaneous dilemmas. For your opponent and for yourself. If one player has a particular card he might use it to gain X but if he utilizes it another way he might gain Y. Now, does he have that card? And if he does, how will he use it? And how badly will it affect you? And what can you do to counter it? Playing a CDG should be about making tough decisions regarding difficult problems and managing the consequences. Simply put, superior games contain high levels of uncertainty.Undoubtedly one of the easiest ways to do this is to have an event that is no more than a one-time exception to a standard rule. That is, to a good game designer every rule suggests a random event that cancels its effect. For example: in Hannibal: Rome vs. Carthage most armies move 4 spaces but with the right card some move 6 (Forced March) and some move 2 (Bad Weather). This increases the Fog-of-War element in a game without noticeably increasing its rules overhead.

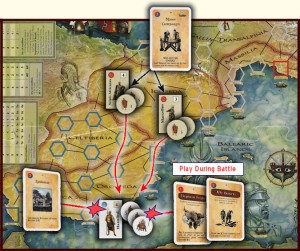

Another way to create tense situations is to use a battle resolution system that gives some level of hope and fear to both players. In HRC this is done by using a separate card system that is famous for giving defenders some slim chance no matter what the odds.

Choice: If games are judged on how well they produce unexpected problems, then those that allow players the widest possible range of actions should succeed.There are at least 5 ways CDG can increase the number of choices available to players: 1) they can have a large event deck, 2) they can increase the number of ways each card may be used, 3) they can ensure each event is easily triggered, 4) they can differentiate cards, which produces more unique situations and 5) they can allow events to be linked into powerful combinations.

A. Simply increasing the size of a random event deck in a CDG may seem the best way to increase a player’s options but things are not that straight-forward. First, extra cards are expensive to print and second, the more cards there are, the less likely it is that any particular card will appear in a game. For example: in Washington’s War, it is entirely possible for the Patriots to fight the American Revolution to a successful conclusion without ever having declared independence, as the “Declaration of Independence” event may not have appeared.

B.  A second way to increase the number of choices a player’s hand produces is to allow cards to be used in multiple ways, perhaps even having multiple events on each card. For example, The War of the Ring is famous for this very approach. However, some other games, such as The Hammer of the Scots and Athens and Sparta, go their own way by having, say, only 6 random events out of an event deck of 55 cards, with the other 49 cards being solely used to move troops. Admittedly, “single use” cards speed play, but they also limit a game’s re-play value as all you see time after time are the same events, merely in a different order: in your first game there is a storm and a while later an earthquake and in the endgame a plague, and in the next game the earthquake occurs first, then later the storm and finally the plague. There are no combinations. There are no “hooks.” If it’s not on the cards, it’s just not going to happen.

A second way to increase the number of choices a player’s hand produces is to allow cards to be used in multiple ways, perhaps even having multiple events on each card. For example, The War of the Ring is famous for this very approach. However, some other games, such as The Hammer of the Scots and Athens and Sparta, go their own way by having, say, only 6 random events out of an event deck of 55 cards, with the other 49 cards being solely used to move troops. Admittedly, “single use” cards speed play, but they also limit a game’s re-play value as all you see time after time are the same events, merely in a different order: in your first game there is a storm and a while later an earthquake and in the endgame a plague, and in the next game the earthquake occurs first, then later the storm and finally the plague. There are no combinations. There are no “hooks.” If it’s not on the cards, it’s just not going to happen.

While there are certain advantages to having single use cards and sporadic random events, there are also certain advantages to building a piano with only 12 keys. It’s just that, all other things being equal, games with a high percentage of “multiple options” cards provide players with richer opportunities.

C. Another method CDG use to expand player’s choices is to see that every card can be easily triggered. Yet there are designers who, instead, prefer to narrow a player’s choice by limiting their ability to activate events. They defend this practice by insisting that “there were historical incidents that were awfully unlikely but they did happen. And as our game was limited to 55 cards, we had to make these events harder than normal to trigger, such as by having players also roll a 1 on a ten-sided die or by demanding the use of a precursor event.”

But that’s the whole point. These designs typically have only so many cards, so why waste 2 of them on things you know won’t occur once in a dozen games? And even if the incident did take place in history why make it so hard to use in your game that it won’t show up anyway? But just as important, weren’t there other interesting events with a higher historical probability that were left out of your system due to space limitations? Why exclude them in order to waste time talking about things you know won’t occur?

On the other side of this coin is the prerequisite problem this approach generates: the first card you need to play in these games usually is useless in itself but if you waste time activating it, it may allow you to generate another event on another card that you may, or may not get, a couple of hours from now. Boooring!

So even if the use of a prerequisite card is thought necessary it should at least be given enough power to accomplish something on its own.

D. Designers would also be wise to differentiate the effects of each card. For example, some designs have cards describing various battlefield events that all produce the same results. Why? It’s like playing poker with a deck that contains 16 aces.

Of course, the easiest way to differentiate events in a wargame is to increase their historicity.

Historicity: should help a game evoke an era’s ambiance while allowing players to produce the widest possible range of strategies.So it’s no coincidence those games that limit their historicity also limit their player’s choices. Washington’s War, for example, neither mentions Hessian mercenaries nor covers political damage beyond the placement or removal of PC markers. Except for moving the French Alliance marker there are no particular political, morale or propaganda dimensions to military actions or failures. There is a card that mentions the Waxhaws Massacre, but “The Butcher” Tarleton’s actions simply produces the removal of one American CU or the generation of a + 2DRM in battle just like numerous other cards. And the publication of “Common Sense” results only in the placing of 3 PC markers. While this approach speeds play, it does so at the expense of depth.

Power: the best designed Card Driven Games should produce random events powerful enough to affect play. Because, if your actions aren’t going to threaten your opponent, why bother doing them? For some reason, over-reliance on historical accuracy perhaps or sheer pedantry, low wattage events infest more CDG designs then we can name. This again misuses a great gaming resource.But the secret to Hannibal: Rome vs. Carthage (HRC) success is not these 5 rules, which it does follow, but a 6th:

Cascading: Exceptional Card Driven Games allow players to join events into ever more powerful combinations in order to advance specific strategies. In other words, their effects snowball. Let’s take a look at this most important principle in detail.

Cascading

Hannibal: Rome vs. Carthage implements “Cascading” so seamlessly that the rules don’t even mention how players could enhance their position by linking events; it just flows from the system itself.

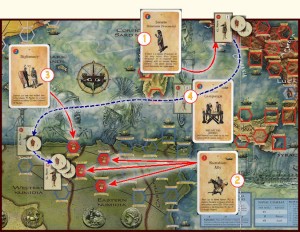

Consider the following example: You are playing HRC as the Roman Republic and have Longus as proconsul, with Flaminius and P. Scipio as Consuls. Lucky you! Your card events are Minor Campaign (which allows a full-strength army to move by sea), Messenger Intercepted (which gives you a card from your opponent’s hand), Diplomacy (which brings one city to your side), Senate Dismisses Proconsul (which allows you to pick a new proconsul), and the Numidian Ally event (which starts a revolt in Eastern Numidia).

Consider the following example: You are playing HRC as the Roman Republic and have Longus as proconsul, with Flaminius and P. Scipio as Consuls. Lucky you! Your card events are Minor Campaign (which allows a full-strength army to move by sea), Messenger Intercepted (which gives you a card from your opponent’s hand), Diplomacy (which brings one city to your side), Senate Dismisses Proconsul (which allows you to pick a new proconsul), and the Numidian Ally event (which starts a revolt in Eastern Numidia).

What can you do?

Well, there are a number of interesting possibilities here. Simply reading the cards will give you some ideas, which is fine. But how likely are they to work? If you revolt Eastern Numidia first, the Carthage player may move Hanno to one of your new PC (political control) markers and your revolt fails. Then again, you could launch a campaign to invade Africa right off, but Carthage has 6 local allies plus Hanno plus the Carthage garrison while you have no safe haven if you lose the battle. Naturally you can plan on not losing but “no plan survives contact with the enemy.” You could use your diplomats to take control of an African port before you invade, but the Carthaginian player might respond by moving Hanno there, as his special ability is removing PC markers in the last space he enters. So once he stops at your port you are back to having no political influence in Africa.

Basically, Rome’s problem is that though some of its events might seem intrinsically more powerful than others, after they are played, it’s the Carthaginian’s turn and he can “unplay” them. For instance, when Rome revolts a typical province, Carthage normally responds by filling the political vacuum thus created with PC markers. And all that the Old Republic has accomplished is to have both sides use one of their cards to no discernible effect. But, on the other hand, if Carthage had no possibility of responding, critics would rightly call the game unbalanced. While problems of this kind often appear in “Igo – yugo” game systems, how well they are handled goes a long way in determining how long a game will remain popular.

In HRC, for instance, while both players are free to play events as they wish throughout a turn, whoever wins the secondary struggle to create an end-of-turn advantage could also produce a super-event.

To begin with, players maneuver to play the last card in a turn. That is, if they let their adversary go first, they go last. So if they give up the near term advantage of going first, they create a long term advantage of having a card in their corner that can be played without a response. Of course, this isn’t always possible. But it occurs. Second, unless it’s absolutely necessary good players do not use interrupt cards, as they affect their end-of- turn situation. Third, they don’t always respond to an opponent’s interrupt card with one of their own as that will cancel a “last card” in their favor. Fourth, they activate the Phillip V of Macedon event when it benefits them, as it forces Rome to lose a card the first time it’s played and Carthage to lose a card the second time it is played. And, fifth, whenever possible, they initiate the Messenger Intercepted event, which gives them 2 more end-of-turn cards.

To begin with, players maneuver to play the last card in a turn. That is, if they let their adversary go first, they go last. So if they give up the near term advantage of going first, they create a long term advantage of having a card in their corner that can be played without a response. Of course, this isn’t always possible. But it occurs. Second, unless it’s absolutely necessary good players do not use interrupt cards, as they affect their end-of- turn situation. Third, they don’t always respond to an opponent’s interrupt card with one of their own as that will cancel a “last card” in their favor. Fourth, they activate the Phillip V of Macedon event when it benefits them, as it forces Rome to lose a card the first time it’s played and Carthage to lose a card the second time it is played. And, fifth, whenever possible, they initiate the Messenger Intercepted event, which gives them 2 more end-of-turn cards.

So, what’s possible?

Well, if we planned our move from the beginning, we could have used the Senate Dismisses Proconsul card early to get Nero on board. Then if we were fortunate enough to produce, say, a 3 card end-of-turn advantage, we might use it to revolt Eastern Numidia by playing the Numidian Ally card, use our Diplomacy card to convert the port of Saldae to our side, which puts our new Roman African province in supply and with a third activation we could move Nero’s army to the African port of Icosium, in Western Numidia, and have him drop off a CU before using his special ability to move 3 more spaces inland to defend Eastern Numidia. With a fourth card, if we were lucky enough to have generated one, we could convert Icosium, which we just garrisoned. As this puts Western Numidia out of supply, Carthage loses a second province at the end of the turn. It takes luck, yes. And it’s risky, yes. But it’s do-able.

Well, if we planned our move from the beginning, we could have used the Senate Dismisses Proconsul card early to get Nero on board. Then if we were fortunate enough to produce, say, a 3 card end-of-turn advantage, we might use it to revolt Eastern Numidia by playing the Numidian Ally card, use our Diplomacy card to convert the port of Saldae to our side, which puts our new Roman African province in supply and with a third activation we could move Nero’s army to the African port of Icosium, in Western Numidia, and have him drop off a CU before using his special ability to move 3 more spaces inland to defend Eastern Numidia. With a fourth card, if we were lucky enough to have generated one, we could convert Icosium, which we just garrisoned. As this puts Western Numidia out of supply, Carthage loses a second province at the end of the turn. It takes luck, yes. And it’s risky, yes. But it’s do-able.

Of course, we could play in a more conservative style and invade Spain (Hispania) instead, either in the far west province of Baetica or in the eastern province of Idubeda. And, obviously, there are many other card combinations that work fine during a turn but can potentially generate an end-of-turn avalanche if we saved them for such an occasion. For example, if we had the Epidemic card, Elephant Fright and Ally Deserts cards, it might pay to attack Hannibal himself. If we had Celtiberia Revolts, Spanish Allies Desert and a Campaign card it may suggest a move into Spain either during a turn or all at once at its end.

Of course, we could play in a more conservative style and invade Spain (Hispania) instead, either in the far west province of Baetica or in the eastern province of Idubeda. And, obviously, there are many other card combinations that work fine during a turn but can potentially generate an end-of-turn avalanche if we saved them for such an occasion. For example, if we had the Epidemic card, Elephant Fright and Ally Deserts cards, it might pay to attack Hannibal himself. If we had Celtiberia Revolts, Spanish Allies Desert and a Campaign card it may suggest a move into Spain either during a turn or all at once at its end.

The point is not which of these plans is best, the point is they are all possible and they all produce secondary problems for players to struggle over. And it’s exactly this depth-of-play that makes Hannibal Rome vs. Carthage the finest Card Driven Game ever published.

Related

Roman Generals in the Board Game Hannibal: Rome vs Carthage

Four Player Variant for the Hannibal: Rome vs Carthage Board Game